One week ahead of Rabelais’ annual cookbook sale, we phoned proprietor Don Lindgren to talk books and collecting. The store, which will celebrate its 10th anniversary next year, is one of a small number in the United States that specializes in cookbooks and an even smaller number that handles antiquarian cookbooks. Of the total inventory at Rabelais – some 30,000 items – about 20 percent are rare books and food and drink ephemera. When we spoke last week, the oldest book in the store dated to 1535. Need some context? It was the reign of English King Henry VIII, a famous, or perhaps infamous, gourmand.

Lindgren got his first bookstore job – in a mall – as a teen. He earned a divinity degree from the University of Chicago, then worked his way up the “rare books food chain” with jobs in Chicago, New York and Boston, eventually specializing in books about the historical avant garde. “Dadaism, surrealism, Futurism, all the -isms,” he said. The art books market collapsed, Lindgren and his wife, Samantha Hoyt Lindgren (then a photo editor and baker), moved to Maine, bought a “small, low-functioning farm” in Alfred, and wondered how to make a living.

One day over lunch at Flatbread Pizza, the couple sketched out a plan to open Rabelais in an empty storefront they’d just driven by in Portland. Why food? “Farm and food were more relevant to us,” Lindgren said. “It was right there in front of us in Maine. The seed of the Portland food scene was already there.” In 2011, to make space for more rare books, they moved the store to North Dam Mill in Biddeford.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity, especially length. Lindgren is an eloquent, fascinating and fluent talker about books, food and collecting.

Q: A while back, you and I spoke about my cookbook collection, and you gave me a hard time about the word “collection.” So define a collection and a collector, please.

A: For me, and for most people in the antiquarian book world, a collection means having some sort of strategy. It could be very simple, like “I want all the books about strawberries.” Then you can get more refined and say, “I want all the American 19th-century books about strawberries.” But by picking a single subject and drawing these books together and spending time with them, you start to see patterns and to learn things that you might not otherwise be able to learn. You don’t have to spend a lot of money. You can choose a very narrow band of things and pursue them. But no matter how small or how inexpensive, perhaps you will create a collection which is interesting and has something important to tell us historically.

Q: Is there a cookbook you’ve never had a chance to hold that you’d like to?

A: I would love to handle a first edition of Amelia Simmons “American Cookery” sometime before I retire. There are only three known copies. I’ve handled copies of nine different editions, but I’ve never seen the first for sale. There are things that are super hard to find, but it would be exciting to see one walk in.

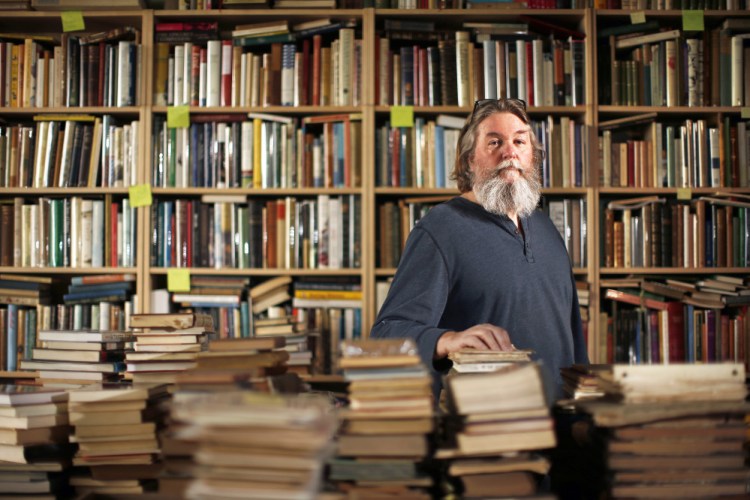

Greg Mitchell, chef of Biddeford’s Palace Diner, browses the bookshelves while Don Lindgren, owner of cookbook store Rabelais Books, looks on. Ben McCanna/Staff Photographer

Q: Do such things walk in? Do you ever go to a yard sale and find the cookbook equivalent of a Van Gogh?

A: Stuff turns up that’s amazing. Here’s one: Somebody brought it to a dealer, a friend of mine in Connecticut. It happened to be an 18th-century English cookbook called “Ladies Delight: Or Cook-maids Best Instructor” (London, 1759). It’s quite a rare cookbook to begin with. Something I’d probably price for $3,500. It had an inscription, and we couldn’t quite make head or tails of it. I finally made out Anthony Benezet. A Frenchman who converted to Quakerism. He settled in Philadelphia. He knew Benjamin Franklin. He founded the first school for girls in America, the first school for African-Americans. He was a very early abolitionist. The book is not just interesting anymore for fans of English cookery, but also for people interested in American history, particularly Philadelphia American history or for people interested in abolition in America, women’s history in America, African-American history in America. The book suddenly goes from telling one story – the story the author had to tell – to telling multiple stories. And that’s what I really look for when I look for what makes a cookbook special.

There is the story the author wants to tell. There is the story of the physical production of the book. Then there is the story of the book as it goes through its own life. It’s hard to find a book that tells all of those stories, but when you do it’s pretty cool.

Q: I know condition is a critical issue for rare books collectors. But these are cookbooks, so is it OK if they have gravy stains or drips of melted butter?

A: There are collectors who pursue perfect copies of things, that are looking for an immaculate copy of an important book. We’ve been lucky enough to sell some books like that. We sold possibly the best copy of “The Joy of Cooking” in existence. The book looked like it was printed yesterday.

Q: This is the original “Joy of Cooking” (1931)?

A: Yes. The dust jacket almost never survived. It’s so rare that we had one that was covered with yellow tape that still managed to fetch a price five times what one without a dust jacket would fetch. We’ve sold a good number of copies without dust jacket, for $3,000 to $5,000, depending on the condition. That copy with the taped-up jacket we sold for $15,000. The step above that is the one that was perfect. That went for $32,000.

Q: Who buys a book for $32,000?

A: Even though that book is perhaps the most famous American cookbook, it was not a cookbook collector. It was a collector of important modern books. That is a field of collection where people are much more driven to find a perfect copy. That’s the only cookbook included in the New York Library’s Books of the Century. But the second part of your question – what about the copy that is dog-eared? I was telling you about a fantastic copy of “The Joy of Cooking.” I’m proud we found it, and I am very proud we sold it. But it’s much more interesting to me to see a copy of a book that has interesting evidence of use – that is the technical phrase – than it is a pristine copy. Sometimes it’s easier to sell the pristine copy. But the book with evidence of use tells a whole story that the pristine copy doesn’t tell us.

Q: Will the Internet kill cookbooks? Has it?

A: It’s certainly changing the way people use cookbooks, in some ways for the better. Online delivers things rapidly with little effort. It’s a great thing for efficiency, but it doesn’t take into account the larger role cookbooks have had historically. Cookbooks are one of the few books that are passed from generation to generation, like the family Bible. Cookbooks are dipped into again and again over a long period, and they change over time. (The owner) might mark it up. They might approve of the recipe, say something is good, say something is not good. They might change the instructions, or add an ingredient, or tell us this was good when they had it at Aunt Julie’s Christmas party.

Q: Should we care if someone writes on their recipe that it’s good, or they enjoyed it at Aunt Agatha’s?

A: I don’t want to make it sound like every book that has been scribbled in has been improved. But when you are looking at older books, it’s a piece of historical evidence. Sometimes the marginalia reveals something that allows us to know who owned something or where something started out or where it moved to.

Q: Do we publish too many cookbooks these days?

A: Absolutely. There are hundreds of thousands of titles in the world. Frankly, most of them are uninteresting and undistinguished. There are whole categories of books I don’t care about.

Q: Such as?

A: Books that are by celebrities. Is it possible that a supermodel could write a good cookbook? Sure. But do I care? No. I don’t. When I look at a book and I look at a recipe – this is true whether it’s a historical book or a new one – the thing that most interests me is whether the book and the author have a point of view. Online recipes can deliver a quality dish, a quality meal. They can do that just as well as a recipe in a book. But what a book gives you, and most online recipes do not, is a point of view.

Q: But thousand of food blogs have a point of view, so may I press you on this point. Will cookbooks disappear?

A: No. And I’m not normally an optimist. The market may end up being much smaller. Most people who used cookbooks in the past just needed some information, and that’s readily available on the internet. But there are some people who will always appreciate what’s special about a physical printed cookbook, which can be very engaging – the typography, the binding, the formatting, the type of paper – so there will remain a market for physical printed books. It’s most likely that the most interesting books will be in that physical market and the least interesting types will cease to have a physical presence.

Q: Which modern cookbooks will last? Which will people be collecting 200 years from now?

A: It’s not always the favorite book of the moment. I certainly think the El Bulli cookbooks will be valuable and interesting in 200 years. Partly because they will be hard to find – they are hard to find now. Also, they made a huge impact both technically and aesthetically in the fine dining world. And there are others like that.

In the complete opposite way, there will be technical books we are not even thinking about right now, like the book that introduced high-fructose corn into our lives. At some point, someone is going to show here’s the moment when Americans chose to poison themselves.

When people are looking for books historically, they are not looking for what to make for dinner tonight. That’s pretty much their last concern. They are looking for historical impact.

Q: Every day you handle books that are hundreds of years old. Presumably, you have the long view. Have people ever been more obsessed with food and drink than we are now? Will our obsession last?

A: The most food-obsessed were the people at the dawn of prehistory, where if they didn’t get food today they would starve. But we are at a moment with the most complex fascination with food that’s ever existed, and that is because – I am trying not to be too geeky – the individuation of food is tied up in who we are, in how we identify ourselves. In the past, regions would express their identities through their food, so you have southern food or food from the Low Country, or food from just one city in Italy. Now it’s very individual, and from person to person, we express ourselves through food in very different ways. Our expression may be that we are gluten-free, or that we only drink a particular type of Bourbon, or that we are obsessed that our food be produced locally. But whatever that individual opinion is, we care greatly about it. And short of there being a terrible calamity that changes the way we eat, the fact that food is greatly important to us will stay with us, because it remains real and sensuous at a moment when other things are increasingly virtual.

Send questions/comments to the editors.