A hotly contested election yielded accusations of cheating. An armed mob threatened the seat of government. A national political leader seemed to be inciting violence.

Yes, Maine was a dangerous place 141 years ago.

Just as this year’s Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol has unleashed a firestorm of recriminations, arrests, frantic security upgrades and threats of more violence, a long-forgotten crisis in January 1880 threw Maine’s leadership into chaos and propelled the participants toward possible armed conflict.

And then, as now, a hyperpartisan political environment fanned the flames of civil unrest.

The cause of the strife was the way votes were counted in Maine’s 1879 election. Republicans thought they had won control of the Legislature and the governorship, but the Democrat-controlled counting of votes produced a different result. Tension, building for months, grew as the state’s supreme court dealt with the matter.

At the height of the unrest, rioters in front of the State House in Augusta threatened to shoot Joshua Chamberlain, the 51-year-old decorated Civil War general who, in a pivotal engagement 17 years earlier, had repelled a Confederate attack during the Battle of Gettysburg.

“That campaign of 1879 has been etched into Maine history as the most extraordinary ever held. It quite literally brought the state to the brink of civil war,” author Neil Rolde wrote in his 2006 biography of then-U.S. Sen. James G. Blaine, who lived across the street from the State House and was thoroughly enmeshed in the controversy.

In the end, the court backed the Republicans, the armed mob melted away without bloodshed, and the political crisis – known colloquially as the “Great Count-Out” or the “State Steal” – eventually subsided.

The two figures who emerged from the chaos with their dignity most clearly intact were Chamberlain, who was a Republican but strove to maintain order impartially as the commander of the state militia; and Charles E. Nash, Augusta’s mayor, who beefed up the city police force and, in cooperation with Chamberlain, deployed officers in a way intended to prevent violence.

As exciting as the crisis was, however, most visitors to the Joshua L. Chamberlain Museum, the general’s former family home in Brunswick, ask about Chamberlain’s Civil War involvement, not the Great Count-Out, site manager Troy Ancona said.

“I do a couple hundred tours a year. I think it comes up about half a dozen times,” he said.

For much of its history, Maine held its state and federal elections in September, nearly two months earlier than other states did, so the results often drew national attention. Also, the terms of office for Maine’s governor and legislators were only a single year in the 1870s, so the slights suffered in one political campaign were hardly forgotten by the time the next one came around.

A more relevant fact, however, was the law determining how the governor was elected. Any candidate who received a majority of votes became governor, but one who drew merely a plurality – more than any other candidate but less than 50 percent – did not win automatically. Instead, the Maine House of Representatives picked two of the candidates and referred their names to the Senate, which chose one of the candidates to be governor.

In 1879, the Republicans nominated Daniel F. Davis, a 35-year-old lawyer and legislator from Corinth, for governor. The Greenbackers nominated Joseph L. Smith, a lumberman from Old Town who had run a year earlier. Alonzo Garcelon, a Lewiston physician and incumbent governor, won the Democratic Party’s nomination by acclaim; but in many districts, Greenbackers and Democrats merged and formed a “Fusion” element that supported Smith.

No one won a majority, so the governor would be chosen by whichever party carried the Legislature.

“At first there was no doubt that the Republicans had carried the Legislature and that Daniel F. Davis would be the next Governor of Maine,” Louis C. Hatch’s multi-volume book series “Maine: A History” summarized 40 years later. Although Davis’ vote total fell short of a majority, a Republican-dominated Legislature would be expected to pick him anyway. However, the account added, the Eastern Argus newspaper, of Portland, claimed intimidation and bribery had tainted the vote.

While the reports submitted by local officers allotted to Republicans a seven-seat majority in the Senate and 29 in the House, Gov. Garcelon and his council announced on Dec. 17. that they reviewed the votes and found the Fusion side to have a majority of nine seats in the Senate and 20 in the House. All their changes in determining the winners were made on technical grounds, such as stray marks on the ballots, spelling errors, local officials’ failure to attest to or sign ballots, or the use of candidates’ initials instead of full names, according to Hatch.

Based on the count of the governor’s committee, Smith would likely have been picked to be governor.

Such manipulation caused public outrage. At the instigation of Blaine, a Republican, protest meetings were held throughout the state. Blaine asked Chamberlain to hold such a meeting in Brunswick, but the general refused, writing to Blaine to urge him to tone down the protests.

“I hope you can do all you can to stop the incendiary talk which proposes violent measures, and is doing great harm to our people,” Chamberlain wrote.

The Democrats said Garcelon and his council were acting in accordance with the law and Republican precedents, noting that Davis himself had rejected ballots from the town of Van Buren on similar grounds only the previous year.

Garcelon, fearing violence, or perhaps intending to provoke it, ordered the commander of the Bangor state arsenal on Christmas morning to send weapons and ammunition to Augusta. A large crowd stopped the munitions wagon in Bangor, however, and it returned to the armory.

In Augusta, Mayor Charles Nash told Garcelon that the city had recruited 200 special policemen to keep the peace, and Nash urged Garcelon not to call out the militia or seek arms from Bangor. Nonetheless, the arsenal finally dispatched 120 rifles and 20,000 rounds of ball cartridge on Dec. 30 in response to an order from the governor.

The Republicans asked Garcelon to refer the matter to the state supreme court. When he did, the Hatch history records, “the judges promptly replied in a unanimous opinion supporting the Republican contentions at every point.”

The ruling surprised the Democrats, but they stood by their decisions. With tension building, Garcelon constituted a militia division and appointed Chamberlain, a Brunswick resident and Bowdoin College president who had been a Republican governor for four years, as its commander. He also told Chamberlain to protect state property until Garcelon’s successor was determined.

The general took command Jan. 6, 1880, dismissed Garcelon’s ragtag group of guards in Augusta and sent the arsenal weapons back to Bangor. He said he would rely on Augusta police to shield the State House.

When the Legislature reconvened, the parties clashed over who was in control and would choose the governor. Despite pressure on him to take sides, Chamberlain said he wouldn’t recognize any governor or Legislature until the supreme court ruled on the Legislature’s status.

Tension escalated. Blaine, worried that a loss for his party could tarnish his national reputation and influence, sent former Civil War general Thomas W. Hyde to Chamberlain with the message that Republican leaders planned to “pitch the Fusionists out of the window.” Chamberlain told Hyde, the future founder of Bath Iron Works, that he would permit nothing of the kind.

A growing band of armed Republicans gathered at Blaine’s State Street home, while the Fusionists, also carrying weapons, met in downtown Augusta. Both sides tried to bribe Chamberlain by promising him a U.S. Senate seat if he would recognize a Legislature dominated by their factions, something that was beyond his legal authority but might be used to their advantage. He declined.

At one point, 25 or 30 men gathered outside the State House, apparently intent on slaying Chamberlain. An aide ran to his office in the Capitol to warn the general.

Chamberlain strode to the rotunda and addressed the crowd. He proclaimed that his task was to “preserve the peace and honor of this State” until a legitimate government was formed. “I am here for that, and I shall do it. If anybody wants to kill me for it, here I am. Let him kill!”

Alice Rains Trulock, who wrote a 1992 biography of Chamberlain, describes what happened next: “With a gesture both dramatic and fearless, Chamberlain threw back his coat and looked his threateners straight in the eyes. The daring words and action had the desired salutary effect: In the sudden, startled silence, an old veteran pushed his way to the front of the crowd shouting, ‘By God, old General, the first man that dares to lay a hand on you, I’ll kill him on the spot!’ Muttering and fuming, the mob dispersed and seemed to melt away.”

Blaine urged Chamberlain to call up the state militia. Chamberlain refused. A plot developed to kidnap Chamberlain, but it failed. As a result of such dangers, he slept in a different location each night.

Chamberlain also learned that some of the Republicans’ opponents were planning to kill Blaine and burn his house, which today is the governor’s mansion. Nash’s police arrested the plotters. After that, Blaine and others began to adopt Chamberlain’s position of awaiting a court ruling.

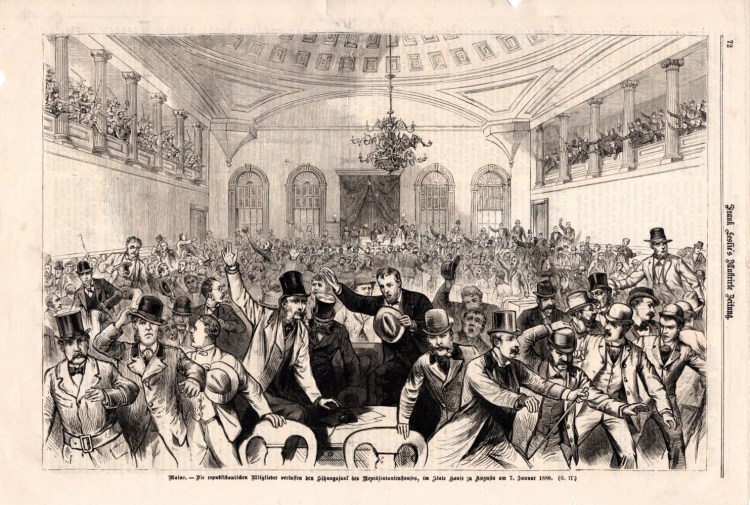

On Jan. 12, the rival legislatures met in the State House, with the Republican version coming to order after members had slipped into the building two or three at a time to avoid observation. A pro-Fusion buildings superintendent locked the room they had planned to use. When Mayor Nash arrived and unlocked the door, the superintendent ran off with the lamplighter, but he was caught and the lighter was recovered. After their meeting, the Republicans’ version of the House and Senate adjourned until the 17th.

In a letter to his wife, Fanny, Chamberlain described the atmosphere of Jan. 15 as “another Round Top,” a reference to his unit’s 1863 bayonet charge at Gettysburg. “There were threats all the morning of overpowering the police & throwing me out of the window,” he wrote, adding that by afternoon, the mob had decided instead to try to arrest him for treason. Neither plan worked.

On Jan. 16 the supreme court ruled that Garcelon and his council had acted unconstitutionally in disqualifying ballots. The Republicans emerged victorious. They convened the next day, 141 years ago today, and the Senate elected Davis governor. Chamberlain recognized him as such and said his own duties were at an end.

“He did the right thing, but it ruined whatever chance he had of a political career afterward,” said Ancona, the museum manager, referring to Chamberlain’s earlier refusal to take sides.

As for Davis, his term featured repeated challenges to the legitimacy of various state officeholders, and militia units occasionally were deployed to the State House as a security precaution. He ran for re-election in 1880 but lost to Harris M. Plaisted, a Democrat.

Blaine eventually won the 1884 Republican nomination for president, but lost the scandal-filled general election to Grover Cleveland. He served twice as U.S. secretary of state.

Chamberlain never ran for elective office again. Still suffering from his Civil War wounds, he died at the age of 85 in 1914. The contempt he had endured in 1880 seemingly was forgotten; only the memory of his Civil War accomplishments remained. Statues of him eventually were erected in Brewer and Brunswick.

Today, amid a wave of efforts to remove likenesses of many prominent 19th-century figures, the Chamberlain statues are still standing, unchallenged.

Joseph Owen is an author, retired newspaper editor and board member of the Kennebec Historical Society. Owen’s book, “This Day in Maine,” can be ordered at islandportpress.com. To get a signed copy use promo code signedbyjoe at checkout. Joe can be contacted at: jowen@mainetoday.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.