NEW YORK — For decades, Jay Gatsby, Daisy Buchanan and other characters from “The Great Gatsby” have been as real to millions of readers as people in their own lives, exemplars and victims of the American pursuit of wealth and status.

Starting next January, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic Jazz Age tale will truly belong to everyone.

The novel’s copyright is set to expire at the end of 2020, meaning that anyone will be allowed to publish the book, adapt it to a movie, make it into an opera or stage a Broadway musical. No longer will you need to permission to write a sequel, a prequel, a Jay Gatsby detective novel or a Gatsby narrative populated with Zombies.

“We’re just very grateful to have had it under copyright, not just for the rather obvious benefits, but to try and safeguard the text, to guide certain projects and try to avoid unfortunate ones,” says Blake Hazard, the late author’s great-granddaughter and a trustee of his literary estate. “We’re now looking to a new period and trying to view it with enthusiasm, knowing some exciting things may come.”

“I wish it were possible for the Fitzgerald Trust to retain copyright,” says Fitzgerald scholar James L. W. West III, a professor emeritus at Pennsylvania State University. “They have been wonderful caretakers of Fitzgerald’s literary rights and his reputation. But under our laws all literary works eventually belong to the people. That’s probably as it should be.”

“Gatsby” has endured in a changing industry and a changing world. It was published in 1925 by Scribner and remains a Scribner book, though now part of Simon & Schuster. The novel, popular with general readers and a standard assignment for students, has sales as dependable as any so-called “backlist title.” When Fitzgerald died in 1940, fewer than 25,000 copies of the book had sold. Now, worldwide sales are nearing 30 million and more than 500,000 copies sell each year in the U.S. alone, according to Scribner.

Publishers specializing in older works already are preparing their own editions. The Library of America will include the novel next year in a planned hardcover volume, edited by West, of Fitzgerald’s work. The Everyman Library, which for years has published the novel in the United Kingdom, will release a hardcover edition in the U.S.

As with such current public domain titles as “Pride and Prejudice,” “The Scarlet Letter”and “Great Expectations,” cheap paperback editions and free e-book editions are likely to proliferate.

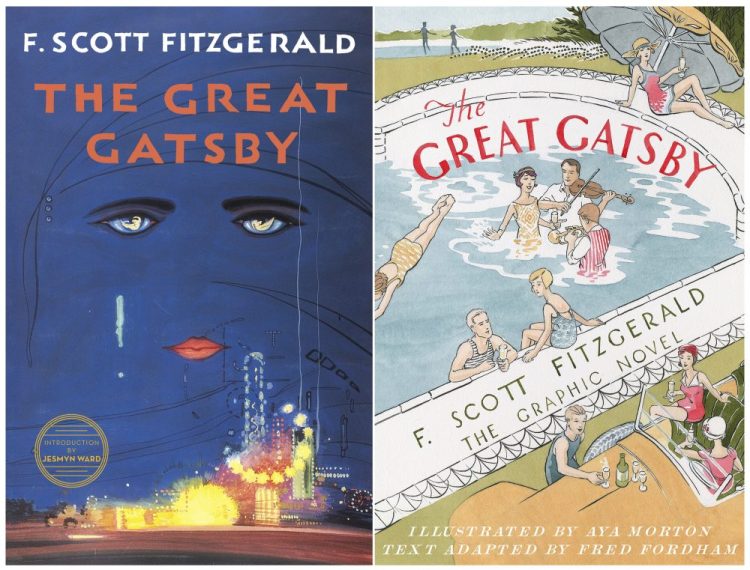

Scribner editor-in-chief Nan Graham acknowledges that sales are likely to fall, but says the publisher is working to hold on to as much of the market as it can, drawing in part on its long ties to Fitzgerald’s heirs. A graphic novel, featuring an introduction from Blake Hazard, is coming out in June. In 2018, Scribner reissued the book with a so-called authoritative text, making minor changes based on Fitzgerald’s own notes. The introduction was provided by Scribner author Jesmyn Ward, a two-time National Book Award winner who wrote of how she, an African American from rural Mississippi, could relate to Fitzgerald’s saga set in Long Island, New York.

“Hungry as I was to escape my own little nowhere country town, my own poor beginnings, as a teen I could only see Gatsby’s yearning. I was too young to know his wanting is wasted from the moment he feels it,” Ward writes. “The seasoned heart aches for James Gatz, the perpetual child, the arrested romantic, bound by one perfect moment to failure.

“This is a book that endures, generation after generation, because every time a reader returns to ‘The Great Gatsby,’ we discover new revelations, new insights, new burning bits of language.”

Hazard was closely involved with the graphic novel, which features illustrations by Aya Morton and an adaptation of the text by Fred Fordham, who worked on the graphic novel of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Hazard researched various illustrators before coming upon “His Dream of the Skyland,” a graphic novel set in Hong Kong in the 1920s that features Morton’s drawings and words by Ann Opotowsky.

Morton told the AP in a recent email that she had long admired 1920s fashion for its “structured graphic design” and “fluid, dreamy quality.” She called Fitzgerald’s novel “incredibly visual,” and was struck by his sense of detail, whether describing cars, emotions or economic status.

“Not only are the hues specific, (blue, yellow, lavender), but what deeply intrigues me is how specific color saturation is to mood and class hierarchy. For example, at the Buchanans, people are wearing white and the colors (greens, reds, peaches), have a very delicate and ‘pretty’ feel,” she wrote, adding that her illustrations also were influenced by car advertisements from the ’20s.

“To me, this theme is central to the story because within American car culture is the notion, or fantasy, of mobility. In other words, the idea that we have the freedom to physically move to another place and leave behind the old problems or even the old person.”

Fitzgerald’s novel has been used in other art forms. It’s at the heart of “Gatz,” an eight-hour stage show from 2010 in which the entire book is read. Several movie versions have come out, from a silent film released not long after “Gatsby” was published to director Baz Luhrmann’s high-energy production in 2013, starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby. Hazard said she enjoyed the Luhrmann film and a 1973 version starring Robert Redford, and imagines other ways the story can be adapted to the screen.

“I would love to see an inclusive adaptation of ‘Gatsby,’ with a diverse cast,” she says. “Though the story is set in a very specific time and place, it seems to me that a retelling of this great American story could and should reflect a more diverse America.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.