Mark Baum (1902-97) was a Polish-born painter who emigrated to New York City when he was a teenager. In the late 1950s, he settled in Cape Neddick, where he painted until just a few months before he died.

Baum’s production falls into two sharply divided modes: He painted landscapes and cityscapes in a primitive style until 1958 when he flipped to an insistently abstract mode. His paintings in the second style were driven by his use of a particular “glyph,” which he would systematically arrange over a monochrome (usually black) painting surface. Both periods of Baum’s painting are on view in “Faith Regained,” an ambitious show organized by Nancy Davidson, curator in residence at the Maine Jewish Museum in Portland.

George Washington Bridge #3 by Mark Baum, 1948. Courtesy of the Mark Baum Estate

While Baum resisted the term “primitive” for his early works, as a description of style, it fits. Baum’s modernist scenes are painted in a loose, cartoony style not beholden to accurate perspective. His 1948 “George Washington Bridge #3,” for example, depicts Manhattan’s West Side Highway with a view up toward the bridge, which is represented as a flat single plane. It is a childlike picture: flat shapes, no modeling (shading), simplified forms and no coherent system of linear perspective. It’s charming and entertainingly fresh. Baum was unquestionably a sophisticated thinker, but whatever his reasons, he painted in a simplified, seemingly naive style.

His 1944 “Waycross, Georgia,” a scene that shows two white houses, a flower-flecked yard, four unmatched trees, and a distant line of evergreens, has a similar quality. Whatever Baum thought he was doing, it looks like an earnest painting by an exuberant but inexperienced young painter. The quirks are enjoyable and unpretentious. The painting is easy to like.

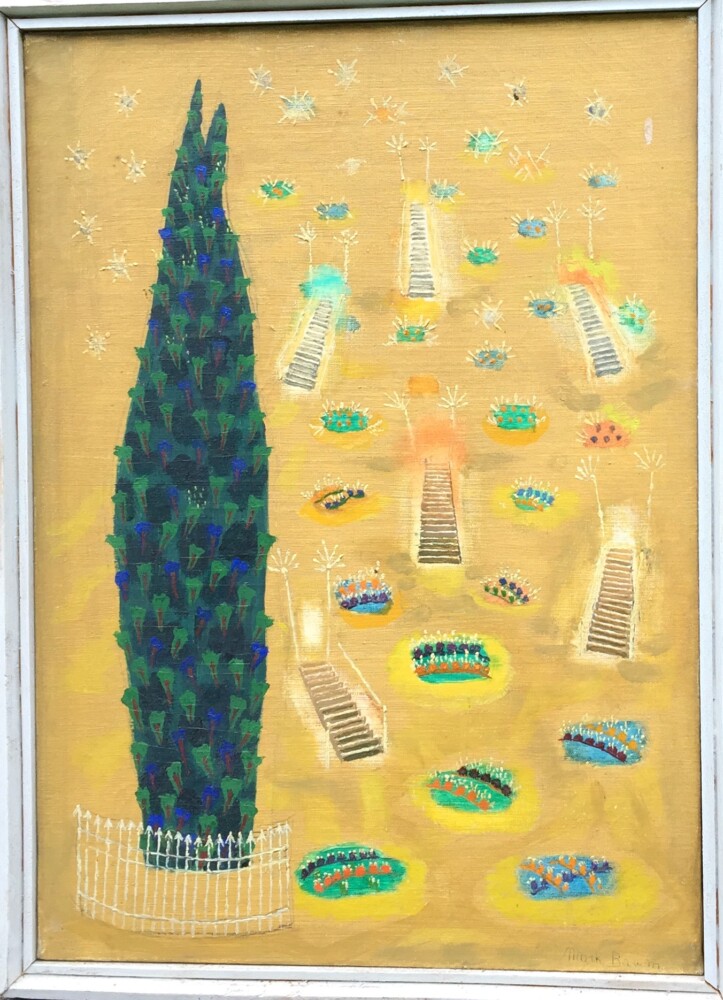

By 1955, however, something was shifting. “Garden of the Guarded Tree,” which he painted that year, reveals a similar style, but the growing sense of spirituality is undeniable. Stylistically, the work has come into focus and it feels – in a good way – very much like the work of painter and designer Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944). On the left side of a sandy ground with no horizon line, Baum presents a blue, black and green cypress tree. The tree, surrounded by a short white metal fence, rises to the top of the picture. To the right, scattered around the ground like effervescent bubbles, are a series of unattached staircases, streetlights and tiny patches of flowers.

While the painterly language is still primitive, Baum is up to something. But is it a tip of the hat to van Gogh, a nod to his spiritual sense of self (“Baum” is German for “tree”) or a meditation inspired by the Kabbalist Tree of Life? The answer is not obvious in a glance, but in light of the growing spiritual and Kabbalah-related imagery in his work, I see it in terms of the esoteric discipline of Jewish mysticism. Once Baum’s spiritual inclinations come into focus, they begin to appear more readily in his earlier paintings, but they are hardly tethered only to Judaism.

While Baum’s work readily reveals connections to painters like Klee and Kandinsky and even early Rothko, I have no doubt that the most important artist for Baum was Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935). A Russian Avant-garde giant, Malevich was one of the most influential painters of the 20th century and an inventor of “non-objective” painting. (Americans often use the terms “non-objective” and “abstract” interchangeably, but artists like Baum insisted on “nonobjective.”) Malevich is best known for his 1913 painting of a black square on a white background.

Lesser known was that Malevich’s family was Polish – he signed his paintings with the Polish form of his name. He was even arrested in 1930 by the KGB on suspicion of Polish espionage (although later released). Malevich’s insistent mysticism would have been appealing to Baum, and his “Theory of the Additional Element in Art” was published in 1927 by the Bauhaus so Baum could easily have read it.

As Baum settled in Maine, his paintings became emphatically nonobjective. He developed what he called “the element,” a glyph that he repeated in clusters as the only element of his paintings. Baum would stencil these onto his canvases and paint them in by hand. (Sound familiar? Check out Jung Hur’s work at the Corey Daniels Gallery in Wells.)

Although Baum developed “the element” over a decade, the break in his work was absolute. He stopped painting charming, quirkily mystical scenes in a childlike style, instead painting his glyphs in flowing groups, often over solid black canvases.

Malevich laid out his “additional element” theory as a way to explain Cubism, a notoriously difficult topic. Malevich’s cubist “additional element” looked like the Russian sickle, a curve with a straight tip. Baum’s “element” resembles it to some extent and even comes to include a Malevich-like rectangle, like a small door at the base of a melon-slice shaped curve.

In Search of Faith by Mark Baum, 1988. Courtesy of the Mark Baum Estate

Baum’s 1988 “In Search of Faith” is made up of three forms: A red and yellow treelike form, a green curve and a large blue sickle underneath the other two. Like his other works in this style, it is a powerful painting, crackling with mystical energy.

Am I criticizing Baum for what appears to me as his proximity to Malevich? Hardly. The brilliant Malevich was clear about what he gleaned from Cubism. (within months of their being painted, 54 cubist Picassos and Braques were on display in Russia). Malevich moved forward from there, inventing the seminal painting movement known as Suprematism. Likewise, Baum may have gotten an idea from Malevich, but he made it his own, using it to make strong paintings that only superficially resemble Suprematism insofar as they feature energized forms flowing in infinite space. Baum’s shapes were comprised of elements, unlike Malevich’s, which were solid.

For the record, before his encounter with Cubism, Malevich painted primitive scenes of peasants in a loose, likable and naive-seeming style.

“Faith Regained” is an excellent and entertaining show. It is also a rare exhibition that could push some viewers to grasp mysticism in abstract painting, that all too fleeting flash of understanding.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

Send questions/comments to the editors.