In an introduction to the catalog for the extraordinary exhibition “Darkness and the Light” now on view at the Maine College of Art’s Institute of Contemporary Art, guest curator and artist Lissa Hunter writes: “I use the terms, darkness and light, as nouns, not adjectives. They have substance. We move into the light. We fear the dark. They are present in our lives and in our psyches as more than descriptors for other words.”

Coming from Hunter, these sentiments are notable since she is widely recognizable as a Maine artist who moves with fluidity between what most people see as the separate modes of art and fine craft. She is the regional queen of shades of gray. Or, at least, that is how she has long appeared through her work.

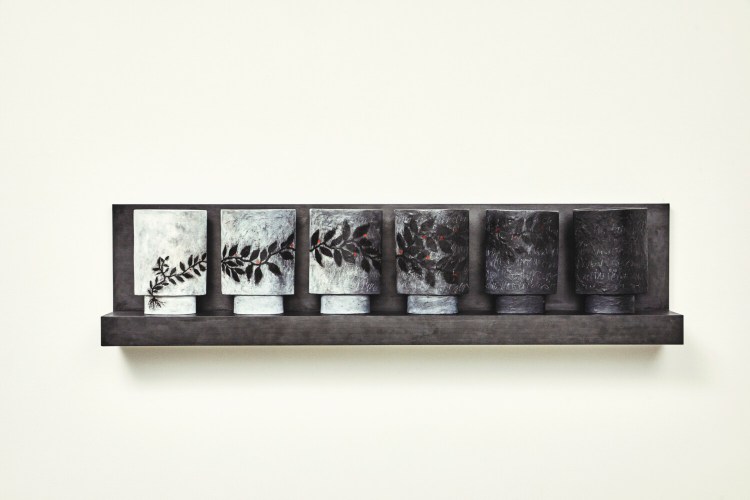

Lissa Hunter, “Slice of Life,” charcoal on panel, 75” x 30”, 2019

When we’re considering the edge between what is “art” and what isn’t, we are engaging in philosophy. We are making moral distinctions among art, craft, kitsch, design and whatever, even if those distinctions appear merely as a wave of a snobby hand. In my experience, it takes a great deal more effort to convince a painter that a ceramic vessel is art than it does to get them to agree that it’s craft or, worse, kitsch. Is it laziness? Maybe. But people in our culture have always found it easier to defend the status quo (especially when it benefits them) than to question it.

Hunter’s own “Slice of Life,” a charcoal painting on panel, best illustrates her point: The vertical panel features plants growing out of a black charcoal ground toward the white light of the sky. The black literally is substance both in the image and representation: The dirt of the ground is solid and, underneath the surface, lightless. Yet Hunter’s “Fade to Black” – a series of six clay vessels that shift (with scratched writing and a floral sprig flowing between them) from white to black – is accompanied by a statement describing how the continuum from light to dark echoes the experience of living and dying. She qualifies it, but the commonly understood outcome is clear. Nonetheless, “Darkness and the Light” provides a rich range of takes on this pair, this continuum, this dialectic.

Alison Hildreth, “Way Points” and “Valley of Bones,” oil on canvas, 84” x 66” (each), 2019

Alison Hildreth’s recent work has focused on darkness as a newly possible place. While her approach has a mortality edge to it, her terms are about exploration: To discover the truly new, one enters darkness and finds a way to light the way. Of her two paintings, “Way Points” seems to literally (and gorgeously) map out these ideas: To the right of a lightning-like white map element of an ancient battlement is darkness. To the blossoming left is an expanding universe of light and curving space-time vectors.

In a show rich with metaphorical and visual depth, the smaller gallery with Hildreth’s work, Hunter’s “Fade to Black,” Tom Hall’s 23-foot four-panel dark-souled clearcut series painting and Lynn Durea’s seven “Forest Forms” (cylindrical Brancusi-esque pedestal-like pieces that reach up to 8 feet) is a high point for gathered meaningful contemporary art in the region. This is true of the entire exhibition. The intensity of the challenging content is matched by the striking aesthetic of the work.

The best moment of “Darkness” is George Mason’s “Deep,” a 20- x 12-foot plaster, encaustic and casein on burlap work that acts like a painting made of a series of maroon shrouds. I believe that it quite specifically refers to the Rothko Room in London’s Tate Gallery – and Mason’s accompanying comment about an “encounter” so “wondrous, unanticipated and unnameable” reinforces my opinion. I have long been a fan of Mason’s brilliant work, but I have never seen it on this scale or so powerful. At a glance, I recognized my own experience of Rothko’s powerful rectangular clouds, balanced so perfectly between light and dark that after a moment, it’s impossible to tell what’s figure and what’s ground. (The result is that you can become visually ungrounded.) “Deep” is experientially masterful, a great work of art.

George Mason, “Deep,” hydrocal plaster, burlap, casein paint, encaustic, 122” x 244”, 2019 MICHAEL D WILSON

I imagine Mason’s “Deep” would soar anywhere, but it could not ask for a better setting than “Darkness,” so emotionally, philosophically and visually intense. Warren Selig’s steel and colored lucite assemblages also push past the edge of the black/white discourse into the issue of color, but they do so by comparing reflected and transmitted light: The transmitted colors on the wall are in fact shadows, and seeing a pink shadow cast by a pink disk reinvigorates the dialogue about shadow as defined by absence rather than presence. The armatures appear as steely gray in front of the white wall, just as their shadows appear lightless gray. But the colors among the shadows challenge us: Are shadows the absence of light? Or are they projections? For people less experienced with light and color, this is a moment to consider the difference between them: Adding all colors of light together gives you white; adding all colors of pigment together gives you black. And, then, of course, there are the Platonic conversations inspired by the Allegory of the Cave. If all we see are shadow projections, do they not become our reality?

Jamie Johnston, “all night long (detail),” paint, graphite, ink on wood, 144” x 600” x 4”, 2019

Together, the work of the 14 artists light the way for rich ideas – visual, philosophical, conceptual and otherwise. I was particularly impressed, however, by some of the denser works that defy verbal readings, such as Jamie Johnston’s wall installation of 40 or so ink-painted geometrical wooden forms “all night long.” Rebecca Goodale’s printed grids featuring floral elements press several points at once: a feminist-inspired deep dig into the content of decorative elements (and piece work), the idea of male-scaled post-war American paintings, the binary logic of yes/no elements capable of infinite expansiveness and so on. And Susan Webster’s “Remembrance Diptych” did something rare with me; I saw the piece as unusual for her, but it was when I read her statement about making by mourning for her recently lost brother that it suddenly came together. It’s a vast work of many elements steeped in process-heavy actions including folding, painting and sewing. To see the work that went into this was one thing, but to find what inspired Webster and what was on her mind during all that work led it to be an almost overwhelming experience of mourning: love, sadness and a sibling’s dedicated vigil of remembrance.

Oh, and there’s more – much more. Hunter and the ICA’s Nikki Rayburn deserve kudos for mounting what is, so far, the most visually satisfying show of 2019 in the region. Moreover, “Darkness” doesn’t make a single claim about its subject – it’s an open book. The artist statements are unusually smart and open-ended. Come and be ready to swim, because the conceptual flood-gates are open.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

Send questions/comments to the editors.