Abdi Abdirahman was studying political science at the University of Southern Maine when he got an email from the dean of the nearby law school.

Danielle Conway remembered him from a campus event earlier that year, and she wanted him to apply for a new summer program designed to promote diversity in the legal profession. Three years later, the 25-year-old has completed his second year at the University of Maine School of Law and is interning at a Portland law firm this summer.

“It really pushed me to go to law school,” said Abdirahman, who was born in Somalia and came to the United States as a child.

That program is one of several that Conway has created and championed since 2015. But she leaves next month for another deanship in Pennsylvania, and her signature initiatives are in financial jeopardy as Maine’s only law school enters a period of transition.

A committee is studying the school’s direction as part of the public university system in Maine, and its recommendations will shape the search for the next dean. That person will inherit the funding battle with system leaders that Conway said factored into her decision to leave.

She said she believes those leaders have been reluctant to give more money to the law school for multiple reasons, including its small size in comparison with the rest of the system and her own efforts to get grant funding to pay for new programs. But she also said she believes implicit bias of sexism and racism made them less receptive to her message.

“You want someone to say, I had a phenomenal experience there, I learned a lot and it’s going to help me in my next leadership challenge,” Conway said of her interactions with those leaders. “I won’t be able to say that, and I’m disappointed that that’s the narrative I carry with me from this experience.”

The University of Southern Maine controls the amount of state money that goes to the law school. In a written statement, President Glenn Cummings said the university was working to get out of a $15 million budget hole while Conway was requesting money for new professors and programs.

“We are committed to identifying and overcoming implicit bias wherever it exists, but it has been our fiscal realities and cost-of-education priorities that have driven allocation decisions for the law school and USM,” Cummings said.

IN THE RED

Based in Portland, the law school has an enrollment of fewer than 250 students and a full-time faculty of roughly 20.

Nationally, fewer students are applying to law school. From 2011 to 2018, the number of applications in Maine dropped from 988 to 574 – a 40 percent decrease. To stay competitive, the law school has increased the amount of money it spends on grants and scholarships.

In 2011, the school reported only a third of the student body got assistance on tuition, and that money almost always covered less than half of tuition. In 2018, two-thirds of students received financial aid from the school, and a quarter of them got half to full tuition. Tuition for this year is $22,290 for Maine residents and $33,360 for non-residents.

As a result, the law school has been in the red for several years, despite cuts to other spending. The university system and USM both tapped reserve accounts to cover that deficit; for the current year, that transfer is projected to be nearly $900,000. The law school’s spending for the current year is $6.6 million.

For years, however, the state allocation for the law school has remained stagnant at about $850,000. Next year, the USM president has pledged to increase that amount by 50 percent. The governor’s proposed budget includes nearly $200 million for the entire university system in fiscal year 2020, and the University of Southern Maine would get $48 million of that money. The law school’s new allocation would be nearly $1.3 million.

“The allocation agreement negotiated between prior leaders at USM and Maine Law is no longer sufficient. … The additional $425,000 in annual support for Maine Law is a starting point with additional conversations to come after the Board receives its recommendations from the special committee on the future direction of the law school,” Cummings said in a written statement.

Conway said that money is not sufficient, and she has still been asked to cut hundreds of thousands of dollars from the budget.

“I think this school and the new dean deserve an upfront investment so that these programs that I’ve started can actually turn into institutional programs that continue to attract quality students,” she said.

ENCOURAGING DIVERSITY

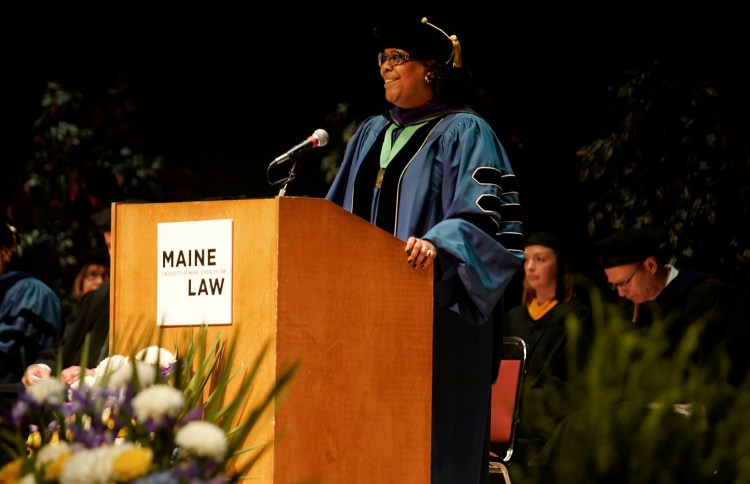

When Conway came to Maine four years ago, the law school touted her reputation as an expert in government procurement law and entrepreneurship, as well as an advocate for minorities and indigenous peoples. She previously spent 14 years teaching law in Hawaii, and her background also includes more than two decades of active duty and reserve service in the Army. Her annual salary was $212,000.

Conway said she took the job because she wanted to lead a public law school. She liked the state and the students when she visited years before to teach a short course on intellectual property law. When she returned as dean, she said she also felt welcomed and supported by her colleagues, the legal community and other professionals she met in Maine.

As the school’s first African-American leader, Conway said one of her goals was to learn about minority communities in Maine and encourage diversity in the legal field. Disclosures required by the American Bar Association show enrollment of minority students at the Maine law school has remained consistent over the last four years at around 10 percent, which is lower than at law schools in Vermont and New Hampshire. An annual report by the Maine Board of Overseers of the Bar does not include information on the race of lawyers in the state.

In her first year, Conway won a $300,000 grant from the Law School Admission Council to start the summer immersion program for underrepresented students – called the PreLaw Undergraduate Scholars Program, or PLUS. That money allowed the school to host 25 students for three weeks each summer, teaching them about the law school application process and what to expect as a law student. It is targeted to students in their first two years of college from ethnic and racial minority groups, as well as those from rural areas or those who are the first in their families to attend college.

Abdirahman remembered participating in mock arguments before a professor who acted as a judge, learning about legal writing and delivering a final presentation on mass incarceration. He met the professors who are now teaching his law school classes, and he plans to stay in Maine upon graduation.

“The law is supposed to represent all of us, not just the few people who have access to it or the few people who have money,” he said.

At the same time, Conway was also in discussions about improving access to lawyers in rural communities. Nearly 4,000 active attorneys live in Maine. More than half – 52 percent – live in Cumberland County. Twelve of the state’s 16 counties get just 20 percent of its lawyers.

So she again went looking for grants, this time from the Maine Justice Foundation, the Maine Board of Overseers of the Bar, and the Maine State Bar Association. The result was the Rural Lawyer Project, a fellowship that sends four students to rural firms over the summer. They each earn between $6,000 and $7,500, and the program costs less than $30,000 annually. Based on applications to the program, school officials said they could award as many as 15 fellowships each summer if they had more money.

One spot this summer went to Ben Everett, who grew up working in the potato harvest in Aroostook County. He deployed to Iraq with the Maine Army National Guard after high school, then came home to work as a paramedic and earn his bachelor’s degree in business administration. He was hesitant to leave his family for law school in Portland until he learned about the Rural Lawyer Project. Now 34, he just finished his first year and will spend the summer in Presque Isle working at a local firm.

“I learned that the school is very committed to getting lawyers out of Portland and into other counties here in Maine,” he said. “That’s what encouraged me to apply to law school. Knowing that this rural fellowship existed was the tipping point for me.”

FUNDING DIFFICULTIES

But the seed money for those programs has run out or will soon.

The grant for the PLUS program lasted only three years. The school sought private donations to keep the program alive this summer, and ultimately cut its size to 14 for budget reasons. This summer is also the final year of the grant for the Rural Lawyers Project.

Dmitry Bam, a law school professor and the interim dean, said a steady funding stream is necessary to continue those new programs and others, like a compliance certificate and an accelerated track that lets students earn a bachelor’s degree and a law degree in just six years.

“If we have that uncertainty year to year, we’re running around trying to raise that money, it’s hard to know we can recruit for next year’s class and know for sure we have the support,” he said.

Asked about future funding, system leaders pointed to a committee that is currently studying the future direction of the law school. They are working to create a new graduate center based in Portland, which would house the law school and other programs. The project is meant to attract more students to graduate school and increase the opportunities to study across disciplines.

“The Board’s special committee to advise on the future direction of the Law School, due to report to the Board this summer, will provide essential guidance for implementing this strategy,” James Erwin, chairman of the University of Maine System board of trustees, said in a written statement.

One of the chairs of that committee is Deirdre Smith, a professor and director at the school’s Cumberland Legal Aid Clinic.

Smith said she could not discuss the findings that will come out in the report in July, but she said the group has been studying the future of legal education and the state’s needs.

“I think there’s a lot of attention on the law school right now because of our leadership change,” Smith said. “I’m very appreciative of the awareness.”

As she leaves for Penn State’s Dickinson Law, Conway said she would advise the next dean to trust his or her colleagues at the law school.

“And be very, very careful of the people in your leadership chain of command,” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.