Before Roy Moore, before Harvey Weinstein and before Brett Kavanaugh, there was William Campbell Preston Breckinridge. In 1893, the 56-year-old scion of a politically powerful Southern family found himself embroiled in a sexual scandal that enthralled the entire country and sparked furious debate. Like his 21st-century counterparts, Breckinridge had much at stake: his marriage, the respect of his children, his career as a Democratic congressman serving Kentucky’s 7th District and, not least, his reputation as an upstanding Christian – one who warned young women against “useless hand-shaking, promiscuous kissing, needless touches and all exposures.” Breckinridge himself did not adhere to such rigorous standards and never expected his paramour to expose their long-term affair: Why would a woman risk divulging the very behavior that would – rightfully, in his view – bring her ruin and shame? Surely the public wasn’t prepared to liberate women from the strict moral code it seldom demanded of men?

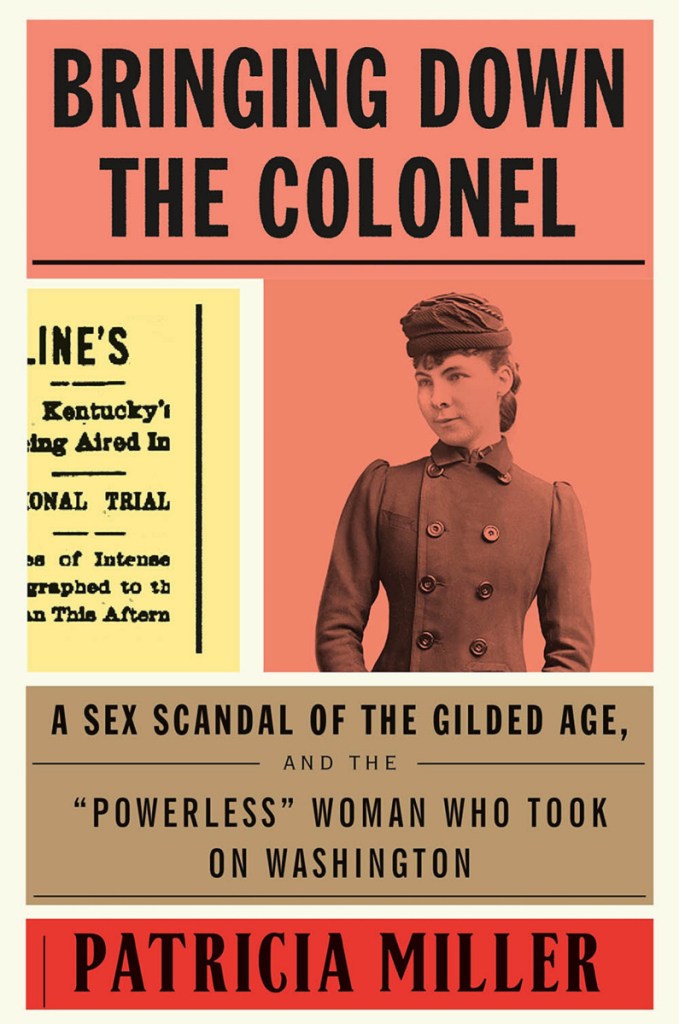

These are the questions at the heart of Patricia Miller’s tantalizing and beautifully researched book, “Bringing Down the Colonel” (“the Colonel” being Breckinridge’s nickname, a reference to his service in the Confederate army during the Civil War). Breckinridge’s victim – or accuser, depending on one’s view – was Madeline Pollard, a woman with none of Breckinridge’s influence but double his cunning. Pollard, nearly 30 years younger than the colonel, was born in Frankfort, Ky., the daughter of a saddler whose shop also offered an array of newspapers and highbrow magazines like Harper’s. She read avidly, mastering Latin and memorizing Shakespeare, and dreamed of becoming a writer. When her father died and left the family on the brink of starvation, Pollard went to live with an aunt in Lexington, where she met a family friend named James Rhodes. He offered her a deal: If he paid for Pollard to attend Wesleyan Female College in Cincinnati, she had to agree to marry him after graduation.

Desperate for an education and eager to amass a cultured circle of friends, Pollard suppressed her loathing for Rhodes and accepted the deal. Months into her Faustian bargain, she happened to meet Breckinridge on a train. Since he had been her father’s political idol, she recognized him immediately, and they shared a brief conversation. Thus began a relationship that would span almost a decade and result in two children (both sent to infant asylums, where they died). Eventually, Breckinridge promised, they would marry.

But unbeknownst to Pollard, Breckinridge was also courting Louise Scott Wing, a 48-year-old doyenne of Washington society. When he married Wing, Pollard retaliated with a “breach of promise” lawsuit, which enabled Victorian-era women to seek legal redress after a broken engagement. Although Pollard’s suit cited $50,000 in damages, she wasn’t interested in money (Breckinridge was famously broke). Her motivation was to challenge the Victorian double standard that judged women’s sexuality while celebrating men’s. Such a case had never been tried before, and she naturally encountered public opposition. “Why on earth do you want to ruin that poor old man in his old age?” a nun scolded Pollard, to which she countered, “I asked her why should that poor old man have wanted to ruin me in my youth?”

Miller spends a significant amount of time providing historical and societal context, relaying fascinating anecdotes that illuminate the evolution of the sexual double standard and the difficulty of Pollard’s endeavor. Beginning with the surprisingly egalitarian mores of colonial times (both mother and father faced nine lashes if a child was born too soon after marriage), Miller delves into the mid-18th-century practice of “bundling,” whereby couples were encouraged to sleep together and pregnancy signified a de facto marriage, and traces the transition to the harsher conventions of the Industrial Age. By the early 1800s, men delayed marriage to pursue education and employment, and an out-of-wedlock child could thwart their upward mobility. Women who had premarital sex now risked social ostracization and ruin, a hazard that persisted into the Victorian era, when their chastity became, in the words of the Middlesex Washingtonian, a “priceless jewel.” By admitting that she had engaged in premarital sex, Pollard was setting herself up for the Gilded Age equivalent of slut-shaming; Breckinridge reasoned that he wouldn’t need to prepare a proper defense, since Pollard’s wicked history should be enough to exonerate him.

A diverse and intriguing cast of characters rounds out Pollard’s saga, and Miller does an admirable job bringing them to vivid life. Nisba Breckinridge, the first woman to pass the Kentucky bar and an eventual staunch advocate for women’s suffrage, unreservedly supports her father but, Miller suggests, is privately tormented by his conduct. Even more titillating are the exploits of Jennie Tucker, a young woman from a prominent Maine family that had been devastated by the panic of 1893. To earn money, and to indulge her own dramatic flair, Tucker becomes a spy – akin to those employed by Weinstein – hired to befriend Pollard, ascertain her motive for the lawsuit and report any information that might ensure a verdict favorable to Breckinridge.

The trial itself devolved, as these things do, into a sprawling tangle of he-said-she-said allegations. Miller deftly sorts through them, but one wishes she had re-created the more cinematic events as they happened, giving the narrative a Rashomon-like quality that highlighted the drama while examining the often subjective nature of truth. The trial does yield some surprises, not least of which is the public’s near-universal condemnation of Breckinridge’s behavior and support for Pollard (fast-forward 125 years, and she might be in hiding after a barrage of death threats).

Anyone emboldened by the #MeToo movement to come forward owes a significant debt to Pollard. Soon after the trial, Miller reports, a letter signed “Many Women” was published on the front page of the Lexington Morning Transcript, urging Democratic Party leaders to withdraw their support of Breckinridge. “Let him sink into the oblivion” of his guilt, they demanded. “Let his voice be silent.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.