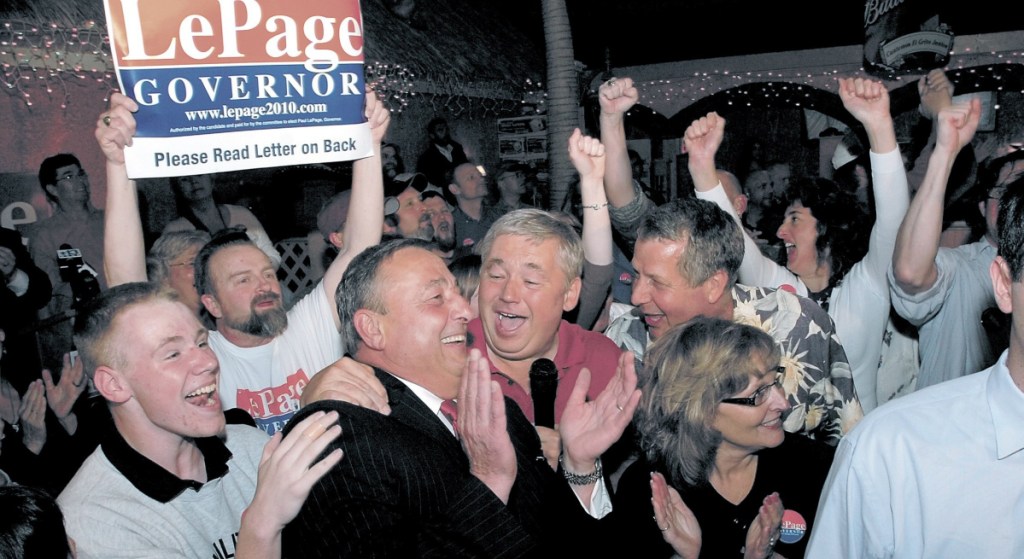

AUGUSTA — Gov. Paul LePage wasted no time turning his 2010 campaign promises into reality.

Just five weeks after his inauguration, LePage submitted a budget proposal that sought to cut taxes, address a massive pension liability and trim welfare rolls by making it harder to qualify for assistance.

He got most of what he wanted from the Republican-controlled Legislature that year – and followed up those initial successes with more tax cuts, welfare changes and fiscal reforms in subsequent years, even when Democrats were in charge.

Yet after eight tumultuous years, LePage’s numerous accomplishments are often overshadowed by his impolitic, occasionally crude and oftentimes slash-and-burn style of governing.

Along the way LePage has offended racial minorities, called a federal judge “an imbecile,” warred with the media and drew his own comparisons to President Trump, proudly proclaiming “I was Donald Trump before Donald Trump became popular.”

“He’s got the best fiscal-responsibility record – both in terms of spending and tax policy – over the last 20 years, certainly,” said Jonathan Reisman, an associate professor of economics at the University of Maine at Machias whose personal politics lean conservative. “In terms of the cohesiveness of the state, no, I can’t say that. The state is as divided as ever, if not more.”

THRIVING ON CONFLICT

Over his two terms, LePage led a crusade to lower Maine’s income tax and estate taxes, achieving gradual rate reductions in both with two of his four budgets. He paid down debts to hospitals, stabilized the state employees’ pension fund, streamlined government permitting by reducing “red tape” and rebuilt Maine’s emergency “rainy day” fund from $0 to $273 million this year.

Maine ended the 2018 fiscal year on June 30 with a $176 million surplus, compared to the $800 million deficit he inherited when entering office at the tail end of the Great Recession.

The verdict is still out, however, on whether LePage will be best remembered for those accomplishments or for the self-defeating tendencies that shrouded his administration in seemingly nonstop controversy.

An August 2016 “town hall” meeting in North Berwick is one of numerous examples.

Billed as an opportunity for regular Mainers to hear from – and ask questions of – the governor, LePage used his regular town hall-style meetings to bring his conservative crusade for lower taxes, cheaper energy and welfare reform to communities throughout the state.

His comments on other topics, however, made the North Berwick event one more footnote in the polarizing, eight-year tenure of Maine’s most controversial, hard-charging governor in decades.

A questioner pressed LePage on why, months earlier at a similar event, he inserted racial tensions into the worsening opioid addiction crisis by saying that out-of-state drug traffickers were impregnating “young white women” in Maine. Never one to back down from a challenge, LePage doubled down by claiming that a binder of mugshots he had been keeping in his office showed 90 percent of those arrested were minorities.

The claim turned out to be false. And in the ensuing days, LePage became the focus of national headlines, cries of racial insensitivity and renewed talk of impeachment among Democrats still stinging from his re-election two years earlier.

There were other racially inflammatory remarks, such as when he suggested a civil rights icon, U.S. Rep. John Lewis of Georgia, owed a thank-you to white Americans who fought to end slavery or Jim Crow laws.

He called a Democratic lawmaker a “little son-of-a-bitch, socialist (expletive),” compared the Internal Revenue Service to the Nazi Gestapo, joked about executing drug traffickers in public, and falsely attributed rising levels of hepatitis C and other infectious diseases in Maine to immigrants. (The cause is a surge in drug-related needle usage among Mainers.)

LePage fought with environmental and conservation groups throughout his tenure, at one point calling Maine’s largest environmental organization one of the state’s “biggest enemies” and holding up voter-approved bonds for land preservation.

Despite his repeated claims he was “no politician,” LePage’s hardball politics scorched not only his Democratic opponents but on occasion other Republican leaders who should have been staunch allies.

“Do I wish he was a little bit more politically correct? Sure, I do,” said Charlie Webster, the Maine Republican Party chairman who helped coordinate the electoral sweep that ushered LePage into the Blaine House and gave Republicans control of the Legislature in 2010. “But I’m not sure how much more would have gotten done.”

‘NOT TURNING THE OTHER CHEEK’

That first year in office demonstrated that LePage didn’t plan to shed impolitic, brash-talking habits that endeared him to some voters on the campaign trail and outraged others.

In his first two months alone, LePage said NAACP leaders could “kiss my butt,” fired up union activists by removing a mural depicting the history of Maine’s labor movement, and suggested the only danger of a now-banned chemical additive was that women might grow “little beards.”

Seven-plus years later, LePage is still both controversial and unapologetic.

“I learned one thing very early on in life: If you turn the other cheek, it hurts,” LePage said recently on Maine Public’s “Maine Calling” radio program. “And I promised if I believe in something, I am not turning the other cheek. I am going to fight back.”

And LePage has fought – with Democrats, Republicans, President Barack Obama, Attorney General (and now governor-elect) Janet Mills, labor unions, judges …

“I think that he is an individual who wants things done and done immediately, and had a tough time dealing with people who may disagree with him,” said Rep. John Martin, an Eagle Lake Democrat and former longtime House speaker.

Martin, who has worked with eight governors during his more than 50-plus years in the Legislature, was among the small handful of Democrats who maintained a steady – if sometimes strained – working relationship with LePage. He attributes that to the fact that he hashed out those disagreements with LePage in private rather than through the press, which the governor both publicly reviles but also skillfully manipulates to get his message out.

“I wish him well,” Martin said. “I think the period we are embarking on will certainly be different, and some people are looking forward to it.”

LePage declined an interview request with the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram. But in a recent lengthy interview with the Morning Sentinel in Waterville, LePage said he did not believe his controversial comments will overshadow his accomplishments as governor.

“The history of Paul LePage is going to be written in five years,” LePage said. “In five years, they are going to miss me.”

FISCAL REFORM – OR HARM?

LePage often lists his fiscal and tax policies among his proudest accomplishments.

Those include reducing Mainers’ income tax levels, stabilizing the state employees’ pension system, paying off $500 million in debts owed to Maine hospitals and renegotiating Maine’s liquor contract. The latter yielded more than $50 million in revenues for the state this year, more than five times the amount under the previous contract.

“Certainly the first major accomplishment was paying off the hospital debt, and that was particularly important because … that was really a violation of the state constitution requiring a balanced budget,” said Reisman, the UMaine-Machias economics professor. Reisman also credited LePage for rebuilding the state’s rainy day fund and limiting the growth of state spending by vetoing bills that had a fiscal note.

“He was unable politically, even when Republicans had control of both houses of the Legislature, to exert the political control to get constraints on spending,” Reisman said. “He had to do it through the veto.”

And LePage made prolific use of his veto pen, rejecting a record 600-plus bills during his eight years.

Of course, LePage’s many critics opposed a number of his financial or tax policies and suggest they had long-standing, negative impacts on the state.

“We certainly feel there was a missed opportunity in the way that the state budgets have been handled by this administration,” said Sarah Austin, a policy analyst with the left-leaning Maine Center for Economic Policy.

Austin criticized LePage for prioritizing tax cuts that disproportionately benefited the wealthiest Mainers. An analysis by the policy center estimates that LePage’s tax cuts will result in nearly $900 million less revenue flowing into state coffers over the next two fiscal years when compared to projections based on the tax code at the time he took office.

“That just gets us into a situation where we are asking less and less of the people who actually have the capacity to pay for things such as education and health care,” Austin said.

She and other critics also contend that Mainers are paying more in local property taxes to compensate for the loss of revenue sharing by the state.

As Waterville mayor, LePage was a fierce defender of revenue sharing – state tax dollars sent back to municipalities – but as recently as 2015 proposed eliminating the practice altogether. Revenue sharing disbursements to municipalities have declined nearly 30 percent, from $96.9 million in fiscal year 2011 to $69.3 million in fiscal year 2017, according to figures from the Maine Treasurer’s Office.

Martin said there is “no question” that LePage is leaving Maine in better shape than when he took office. But that “would be a different story” if the national economy remained mired in the recession that LePage’s predecessor, Democratic Gov. John Baldacci, faced in the latter years of his administration.

“He can’t take all of the credit for it,” Martin said of LePage. “Maine’s economy by itself is not the result of the governor or the Legislature. It is more the result of the national economy and what happens across the country. If you look at states across the country, many have surpluses.”

SOCIAL SERVICES

LePage also touts his administration’s “welfare reform” measures that dramatically reduced the number of Mainers receiving public assistance.

Participation in the food stamp program, for instance, fell 20 percent after eligibility requirements were tightened. The number of households receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, declined by more than 60 percent between 2012 and 2017 after the LePage administration tightened eligibility requirements and instituted a five-year lifetime cap on benefits.

“I think the best thing that we’ve done, while it goes unnoticed most of the time, is the welfare reforms that we’ve done are really helping a lot of good families,” LePage told Maine Public. “The people that are off welfare now are earning 114 percent more in revenues than they ever had in their lives. That’s on average.”

But defenders of Maine’s safety net programs counter that falling enrollment numbers mean more people are going without help, not that demand for assistance has dropped.

The number of children in “extreme poverty” – that is, living in families earning less than 50 percent of the federal poverty level – rose from 17,000 to 23,000 between 2010 and 2014 before dropping back down to 14,000 last year, according to the annual Kids Count report conducted by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Maine also had the nation’s ninth-highest percentage of “food insecure” households – at 15.8 percent – from 2013 to 2015, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture statistics. While that percentage has since fallen to 14.4 percent last year, Maine is still well above the national average of 11.8 percent.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington, D.C.-based liberal think tank, also accused the LePage administration of issuing a “methodologically flawed report (that) cherry picks data and omits key findings” to suggest the five-year TANF limit helped families get off welfare.

“It hides facts that show that most families that reached the time limit have not been able to replace the cash assistance they lost with income from work, putting the children in these families at great risk of experiencing high levels of deprivation and stress, which have lifelong negative consequences,” the center wrote in August 2017.

The governor steadfastly opposed Medicaid expansion. In addition to vetoing five bills to provide health coverage to an estimated 70,000 low-income Mainers, LePage has refused to implement expansion despite voters’ overwhelming approval of a November 2017 ballot initiative. Last month, a court ordered the administration to begin implementation but he is leaving that to his successor, Gov.-elect Janet Mills.

In another controversy, LePage prohibited Portland from using state-funded General Assistance dollars to help immigrants planning to seek asylum in the U.S. And his administration’s repeated attempts to rein in the use of EBT – or electronic benefit transfer – cards for purchases of soda, candy and other foodstuffs ran into opposition from lawmakers.

The LePage administration was also criticized for failing to take more aggressive steps to address an opioid addiction crisis that has killed thousands of Mainers in recent years. While the administration and Legislature earmarked an additional $6.6 million for treatment this year, treatment advocates have often criticized LePage for putting too much emphasis on law enforcement and not enough on treatment.

THE NEXT CHAPTER

Mills, Maine’s Democratic governor-elect, often uses the phrase “turn the page” as she pledges to bring a more collaborative, less confrontational governance style to the Blaine House. It’s also a twist – or perhaps a jab – at LePage’s campaign slogan of “Turn the page with Paul LePage.”

“It is time for a new day in Maine,” Mills told electrified supporters on election night after she was declared Maine’s first female governor-elect. “I stand here before you on this November night to say that I have heard the message loud and clear: We will lead Maine in a new, better direction.”

Webster, the former Maine Republican Party chairman and a close ally of LePage, said he believes LePage would get elected again despite the controversies of the past eight years.

“If he ran against Janet Mills, I believe he would have won,” Webster said.

The “blue wave” that elected Mills and other Democrats up and down the ticket this year would argue otherwise on that point. But there is no question LePage remains popular with the Republican base that elected him with 38 percent in 2010 and an even larger margin four years later.

“I think his philosophy resonated with folks,” Webster said. “For the average guy, they want government out of their lives, they want less taxes and less spending.”

For his part, LePage has been characteristically vague about his post-governorship other than his plans to move to Florida with his wife, Ann. He has expressed an interest in teaching college courses or perhaps joining the Trump administration as an ambassador or other role that wouldn’t require him to live in Washington.

But he has also said he’ll be watching closely to see if Mills and Democratic lawmakers unravel what he regards as his administration’s fiscal and social successes. And he told the Morning Sentinel that he planned to leave a note for Mills on her pillow in the Blaine House.

“If you mess it up, I’m your opponent in 2022,” LePage said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.