Al Hawkes, a bluegrass and country music pioneer from Westbrook who once advised Chet Atkins about making better recordings and helped integrate bluegrass music as a member of the first popular biracial duo, died early Friday morning at age 88.

Fixtures in Westbrook, Barbara and Al Hawkes co-owned a television repair shop and The Sound Cellar, both on Route 302. Barbara Hawkes, a longtime city clerk, died Dec. 3, and Al Hawkes died Dec. 28.

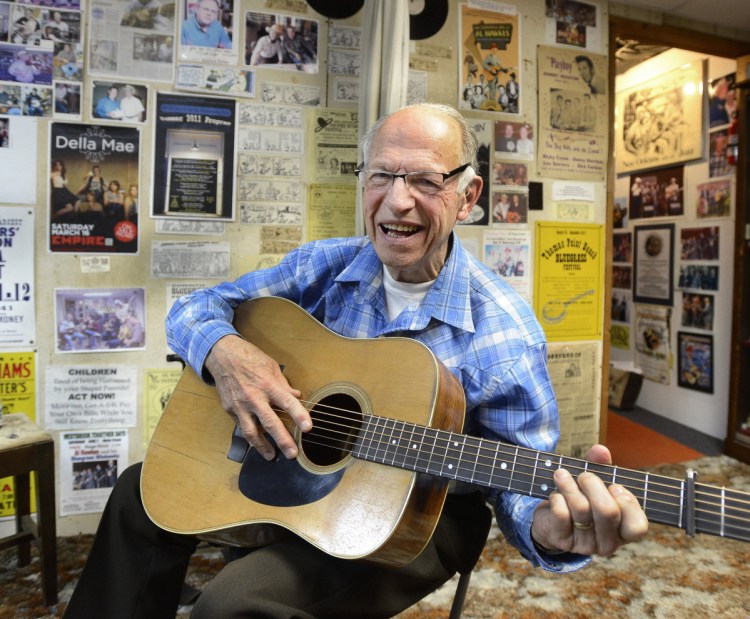

He was considered country music royalty, a singer and songwriter with a good voice and a friendly personality who could also play the guitar and mandolin. The International Bluegrass Museum in Kentucky recognized Hawkes for his pioneering work, and he is a member of both the Maine Country Music Hall of Fame and America’s Old-Time Country Music Hall of Fame.

Hawkes was also a producer and engineer who cared about making high-quality recordings, of his own music and that of friends like guitarist Lenny Breau and country singer Dick Curless, that would last over time, said his longtime friend, rockabilly musician Sean Mencher. “In my mind, he’s a giant. He may not have been as well know as Sam Phillips or Norman Petty, but he recorded music that was just as influential,” Mencher said, naming the producers for Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly and others.

The recordings Hawkes, Breau and Curless made together at Event Records studio in Westbrook in the 1950s and early ’60s are some of the best examples of regional American rockabilly and bluegrass music, and many have been reissued by record labels in Germany and England, said Nate Gibson, an American music folklorist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

“He loved bluegrass, he loved country, he loved hillbilly, he loved Western swing and he loved rockabilly, and he recorded all of it,” Gibson said. “He made some of the best bluegrass and some of the best rockabilly recordings that there were in the 1950s, and his recordings were farther-reaching than Al and a lot of other people realize. People all around the world look at those records he made in Westbrook, Maine, as examples of how to record really great music on a very limited budget. He was very talented.”

Former Maine Sen. Olympia Snowe celebrated Hawkes’ 80th birthday on the floor of the U.S. Senate, calling him a “Maine and national treasure.” In 2010, Maine Public aired a documentary about his life, “The Eventful Life of Al Hawkes.”

Hawkes had been unresponsive and in hospice for several days before he died around 12:45 a.m. Friday, according to family members and friends who posted the news. He turned 88 on Christmas Day.

In recent years, Hawkes could no longer play mandolin or guitar because of the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Hawkes was diagnosed with the disease, a nervous system disorder that affects movement, in 2000.

A vintage poster, photographed in 2015, features Maine bluegrass pioneer Al Hawkes of Westbrook.

Hawkes’ wife, Barbara, died Dec. 3 at age 86. She was a longtime city clerk for Westbrook and co-owned, with her husband, a television repair shop and The Sound Cellar, both based at Hawkes Plaza on Route 302 in Westbrook. The plaza was known for its large sign and a 13-foot statue of a TV repairman, which the family built after Hawkes learned welding in 1962.

Hawkes, who was born in Rhode Island and moved to Maine as a child, became a fan of bluegrass as a boy and learned to play guitar and mandolin. When he was drafted into the military in the early 1950s, Hawkes was sent to northern Africa and was featured on an Armed Forces Radio station there. After returning to Maine, he often met up with and performed with bluegrass musicians from across New England.

“He put Maine on the bluegrass map,” said Joe Kennedy, who founded the Bluegrass Music Association of Maine with Hawkes.

The International Bluegrass Music Museum in Kentucky recognized him as one of the “Pioneers of Bluegrass.” He was half of a duo with Alton Myers, making them the first interracial duet in bluegrass, and bluegrass musicians from around the country visited Hawkes’ recording studio in Westbrook to produce music with him.

In 1956, Hawkes started his own recording label, Event Records, and recorded the Bailey Brothers, Don Stover and other leading regional performers of bluegrass, rockabilly and country music, among other genres. The record label folded in the early 1960s after a fire. The equipment Hawkes used to make those records has been repaired and relocated to Acadia Recording Company in Portland.

Al Hawkes plays the mandolin at the Ossipee Valley Bluegrass Festival in Hiram in 2008. Hawkes was known nationally for his playing, songwriting, singing and recording.

Event Records recorded several dozen 7-inch singles, including “China Nights” and other early songs by Curless; and “Baby, Baby” by Curtis Johnson and the Windjammers. Breau, then still a teenager who later achieved fame as a jazz and hybrid guitarist, made his first recordings at Event Records as a studio musician. In later years, Hawkes would tell a story about getting a phone call in his Westbrook studio from Chet Atkins, by then one of Nashville’s top guitarists, asking how he managed to record Breau’s guitar so well, Mencher said.

He recalled sitting in the studio listening to Hawkes play examples of dozens of the early Event recordings and telling stories about the sessions and the musicians. “He started pulling out tapes of Lenny Breau at 14 and all this Event Records stuff, and it blew my mind. It was like a treasure trove about what is so great about America and American music and the influences and the patchwork and the cross-pollinations. It only happens in American music where you get that mixture of the jazz and blues with European influences and African influences, with Scottish and Irish fiddling,” he said. “We predominantly know that music as being from the south, but there are pockets regionally, and Al Hawkes represents a deep pocket of that regionalism.”

Hawkes’ love of music continued throughout his life, and he often performed at festivals throughout the state. His library of recordings is massive, and considered a valuable archive and resource.

Family friend Eileen Grant Szeto said it always impressed her that Hawkes led the effort to integrate bluegrass music by touring with Myers in the early 1950s. Their example of finding common ground stands today as an example of how to get along, she said. “That was rare back then and it’s rare still,” Szeto said. “They found out they liked the same kind of music, and they became a duo.”

In recent years, Hawkes’ songs focused on Maine, and he released a CD in 2015 called “I Love the State of Maine.” Hawkes wrote all but two of the songs on the album, and most focused on his memories of events or people in the state or places in Maine, such as Westbrook, Down East Maine and the North Woods.

“I hope that some of the songs on the album make people smile, be a little bit happier about the state of Maine,” Hawkes said in a 2015 interview.

Hawkes donated the proceeds from the album to the Maine Parkinson Society.

After news of his death was posted early Friday on his Facebook page, Hawkes’ friends shared memories of the musician and shared photos of him performing on stage.

“Whether having a drink with him and Barbara at Lenny’s, talking at a local event or the few times he took the stage to play with Pete Witham, I will always remember Al Hawkes for his kindness, humor and passion for music,” wrote James Tranchemontagne, owner of The Frog and Turtle in Westbrook. “A kind passionate man with love for all.”

Musician Valerie Smith of Missouri posted on Facebook that the music world lost “a very special ‘Pioneer of Bluegrass.’ ”

“He not only helped build the foundation of the bluegrass industry and music, but also he was a bright light,” Smith wrote. “Al was so kind to share his stories and music with me.”

Mencher called Hawkes “a great friend, a very, very dear friend, an inspiration and a motivation and he will forever be in my heart. God willing, I will have some of his legacy in my heart and soul that I will be able to share every time I play music, to carry it on.”

Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Staff Writer Ed Murphy contributed to this report.

Send questions/comments to the editors.