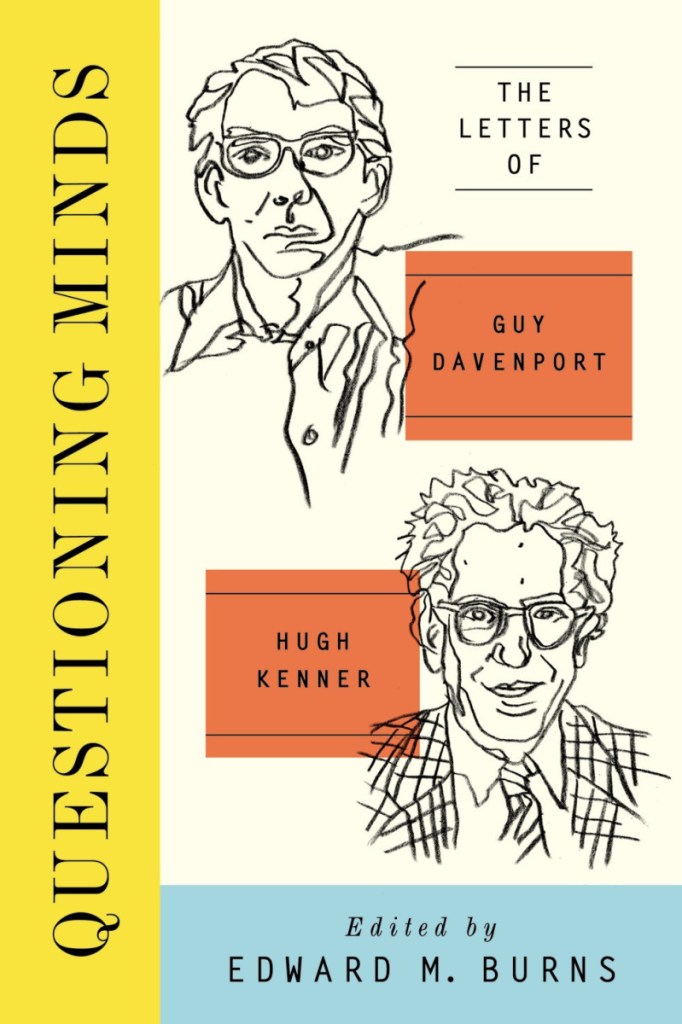

“Questioning Minds: The Letters of Guy Davenport and Hugh Kenner” has been for me, and will be for many others, the most intellectually exhilarating work published in 2018. In roughly 1,000 letters, mainly from the 1960s and ’70s, two of the great literary polymaths of the second half of the last century converse about art and literature, scholarship, translation, the follies of academe, and the life of the mind. As a bonus, the book’s redoubtable editor, Edward M. Burns, identifies every name, reference and allusion, elevating his sometimes essaylike notes into an integral, invaluable part of the correspondence itself.

Nearly all of Hugh Kenner’s work can be viewed as an extended commentary on 20th-century modernism or, as his 1971 magnum opus called it, “The Pound Era.” Not only did Kenner (1923-2003) produce groundbreaking studies of James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Wyndham Lewis, Ezra Pound and Samuel Beckett, but his own darting prose, abounding in surprising factoids and anecdotes, also makes his writing vastly entertaining; Guy Davenport once compared reading his friend’s work to the thrill of opening presents on Christmas morning. As one might expect from a star student of Marshall McLuhan, Kenner regularly probes the effect of new technologies, such as the typewriter and telephone, on early modernist literature. This McLuhanesque bent eventually led him to bring out entire books about R. Buckminster Fuller, the inventor of geodesic domes, and cartoon legend Chuck Jones, the genius behind Bugs Bunny and Wile E. Coyote.

On one of the best days of my life, I spent seven hours talking with Davenport (1927-2005) at his home in Lexington, Ky. If you’ve ever read “The Geography of the Imagination,” “Tatlin!” or any of his other collections of stories and essays, you know that Davenport’s curiosity and learning were seemingly unbounded. He translated Sappho, Heraclitus and Archilochus, promoted the films of Stan Brakhage, kept up a vast correspondence (with, for example, anthropologist Rodney Needham and Russian scholar Clarence Brown) and for relaxation painted or read the novels of Georges Simenon. He brought out important monographs about the artists Balthus,Paul Cadmus and Charles Burchfield, while his University of Kentucky courses might address anything from the writings of Victorian mastermind John Ruskin to the cosmology of the Dogon culture of Africa. When Davenport focused his capacious intelligence on, say, Kafka’s story “The Hunter Gracchus” or the biblical paintings of Stanley Spencer, the result was as much a work of art as a work of explication.

While Kenner’s letters in “Questioning Minds” tend to dwell on his current projects, Davenport ranges more widely, not just discussing scholarly undertakings but exuberantly relating holidays with girlfriends and, more cagily, with motorcycling boyfriends. A brilliant draftsman, he works up humorous pen-and-ink caricatures for Kenner’s “The Stoic Comedians: Flaubert, Joyce and Beckett” while also starting to develop his assemblages, sui generis composites of speculative fiction, literary history, artwork and criticism. The very first of these, “The Aeroplanes at Brescia,” imagines a meeting – which could have happened – between Kafka and Wittgenstein at an early air show.

As gossip alone, “Questioning Minds” is irresistible. Yet even if you don’t know anything about Sheri Martinelli (painter and modernist muse) or John Cournos (poet and Dorothy Sayers’s lover) or Frank Meyer (the eccentric literary editor of National Review, to which both men contributed), don’t worry: editor Edward Burns will fill you in. For example, he notes that Davenport’s friend Laurence Scott knew eight languages, sold spot drawings to the New Yorker and worked for a company that built composting toilets. Burns also points out occasional mistakes, as in “GD is wrong, the word only appears in Aristotle’s ‘Historia Animalium.'”

As is usual in literary and scholarly circles, both correspondents periodically grouse about the iniquity of publishers, English departments and magazine editors. Each indulges in frequent wordplay: Kenner comes up with “Adipose Wrecks,” while Davenport prefers the stiletto-stab of “Wordswords.” When Kenner buys an early computer, Davenport sticks with drafting pens and his trusty electric typewriter, but shells out for a home photocopier. Having been born into a poor family from Anderson, S.C., Davenport unashamedly admits that “personally, I don’t like nuvvles [novels] about the rich. … The sun-tanned aristocracy makes me nervous, and I haven’t the slightest pity for the muck they get themselves into.”

Unexpectedly, both men rightly revere the artistry of the multifaceted if sometimes seemingly frivolous Jean Cocteau. After Kenner shares his chance discovery of Jorge Luis Borges’ “Labyrinths,” Davenport urges his friend to read Eudora Welty and “the finest allegory I know of in modern times”: Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings.” When Kenner extols Charles Babbage, creator of the analytic engine, Davenport responds that the visionary engineer might have been a model for Sherlock Holmes. Above all, the two champion the most exacting standards in whatever they undertake: As Davenport says, “Shoddiness demoralizes.”Still, when Kenner praises his friend’s archival intelligence, the latter replies: “You more than any ought to know what a rag bag my mind is, a kind of Victorian attic. I know that Whitman was at Poe’s funeral and that G.K. Chesterton weighed 280 pounds at forty and William Blake carried ‘The Rights of Man’ to the publisher for Tom Paine (who was in jail, as usual).”

Let me end with a confession: This review draws mainly on Volume 1 of “Questioning Minds.” I so loved spending time with Kenner, Davenport and Burns that I decided to save, and slowly savor, the second volume, keeping it for my autumn bedside reading. In a world of fast-buck best-sellers, Counterpoint has brought serious readers a lasting treasure.

Send questions/comments to the editors.