WASHINGTON — The Senate passed the final version of a sweeping opioids package Wednesday afternoon and will send it to the White House just in time for lawmakers to campaign on the issue before the November midterm elections.

The vote was 99 to 1, with only Utah Sen. Mike Lee, a Republican, opposing it.

The bill unites dozens of smaller proposals sponsored by hundreds of lawmakers, many of whom face tough re-election fights. It creates, expands and reauthorizes programs and policies across almost every federal agency, aiming to address different aspects of the opioid epidemic, including prevention, treatment and recovery.

It is one of Congress’ most significant legislative achievements this year, a rare bipartisan response to a growing public health crisis that resulted in 72,000 drug-overdose deaths last year. It marks a moment of bipartisan accomplishment at an especially rancorous time on Capitol Hill as senators debate Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court.

There were 180 overdose deaths in Maine through June 30, down just slightly from the 185 drug-related deaths reported for the same period last year, according to figures released in September by the Maine Attorney General’s Office.

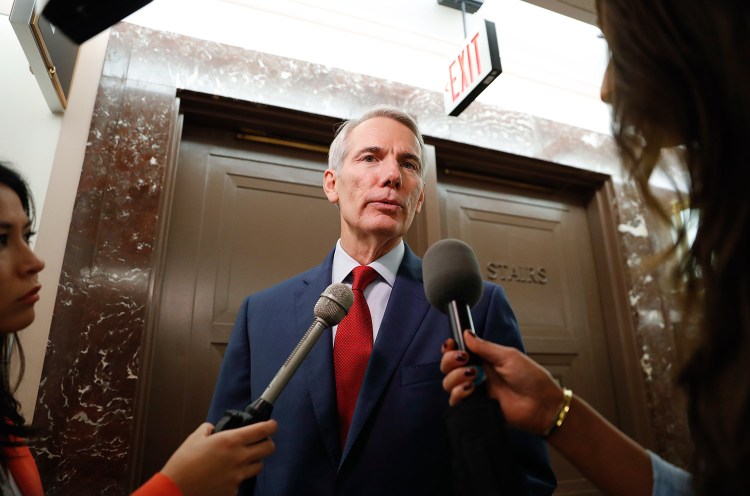

Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, who sounded the alarm on opioid addiction four years ago, is credited with the slice of the bill that could have the greatest effect. It will require the U.S. Postal Service to screen packages for fentanyl shipped from overseas, mainly China. Synthetic opioids that are difficult to detect are increasingly being found in pills and heroin and are responsible for an increase in overdose deaths.

“I will say getting that passed, to me, is just common sense. I think it’s overdue. I’m disappointed it took us this long,” Portman said in a floor speech Tuesday. “How many people had to die before Congress stood up and did the right thing with regard to telling our own post office you have to provide better screening?”

On Wednesday, just before the vote, he called it a, “glimmer of hope.”

The bill’s passage comes a year after President Trump declared the opioid crisis a national emergency. The Senate vote is the last step before he signs the measure into law. The House passed it 393 to 8 last week.

Public-health advocates laud the bill’s increased attention to treatment, which they say is the key component to overcoming addiction. The legislation would create a grant program for comprehensive recovery centers that include housing and job training, as well as mental and physical health care. It would increase access to medication-assisted treatment that helps people with substance abuse disorders safely wean themselves.

Another major aspect of the bill is the change to a decades-old arcane rule that prohibited Medicaid from covering patients with substance abuse disorders who were receiving treatment in a mental health facility with more than 16 beds. The bill lifts that rule to allow for 30 days of residential treatment coverage.

The opioid crisis has hit communities big and small, rural and urban, in states red and blue. The more cynical view of the bipartisan work on this package is that it’s an easy election-year win. Although it contains provisions that help address the problem, it does not dedicate the level of funding and long-term commitment needed to fight a crisis of this magnitude, many experts say.

“This legislation edges us closer to treating addiction as the devastating disease it is, but it neglects to provide the long-term investment we’ve seen in responses to other major public health crises,” said Lindsey Vuolo, Associate Director of Health Law and Policy at Center on Addiction. “We won’t be able to make meaningful progress against the tide of addiction unless we make significant changes to incorporate addiction treatment into the existing health care system.”

Congress has appropriated $8.5 billion this year for opioid-related programs, but there’s no guarantee of funding for subsequent years. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Md., have proposed committing $100 billion over 10 years to fighting the opioid crisis.

It is modeled after Congress’s robust response to HIV/AIDS.

Send questions/comments to the editors.