Even when he was winning Emmy Awards for his thoughtful character development and plot lines on the groundbreaking NBC drama “Hill Street Blues,” colleagues knew Jeffrey Lewis was not your average TV writer.

“Whenever there was something completely original and surprising in a script, it was usually Jeff who wrote it,” said Jacob Epstein, who also wrote for “Hill Street Blues.” “We could see he had a novelist’s gift for character, he had a much greater compassion for the character than the rest of us.”

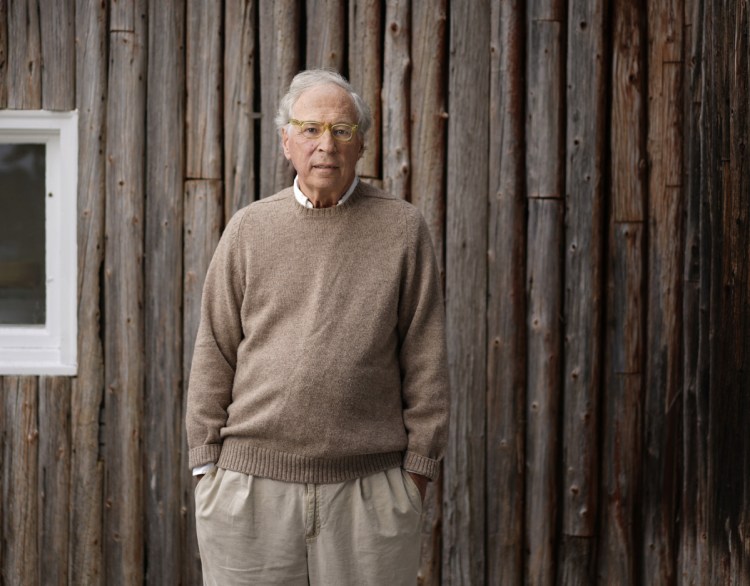

Lewis, 74, walked away from TV writing a few years after “Hill Street Blues” went off the air in 1987. He and his wife bought a house in Castine in 1991, and he decided to write novels instead. He’s published seven of them since 2004. His latest is “Bealport,” the story of a coastal Maine factory town losing its largest employer, which came out in August. He’ll give a talk about it Tuesday at Longfellow Books in Portland.

“I worked on a couple of other shows (after ‘Hill Street Blues’), but I realized I didn’t want to do series TV,” said Lewis, who was also a producer of “Hill Street Blues” for a time. “A long-running series is stretched out with the same ideas and the same feelings, with the hope people will form a habit of watching the show. So you want to add things that are new, but not too new.”

Lewis, who splits his year between Los Angeles and Castine, says he finds it harder to write in Maine than in California. That’s because his Castine house is near the ocean and a lighthouse, and he finds summer in Maine far too interesting to allow him to stick to a strict writing schedule. Voyaging someplace by boat for a picnic lunch is too tempting. But in Los Angeles, keeping his nose in his writing is easier.

His latest novel, “Bealport,” is set in a coastal Maine town. It’s a one-industry town, as many in Maine have been over the years. Lewis said he drew some inspiration from Bucksport, not far from Castine, a town built around a paper mill and its jobs.

The fictional town’s name comes from Beals Island, because Lewis liked the sound of it. He added “port,” because so many coastal towns around here include that word. Bealport, in the novel, is near Penobscot Bay and not far from Belfast and Augusta.

Lewis said he decided to make shoes the town’s main industry because he knew that Maine, and New England generally, have a long history of shoe making. In his novel, the Norumbega shoe factory is not doing well, and a wealthy summer visitor decides on the spur of the moment to buy it.

Lewis said the novel is an effort “to describe with some sympathy” the plight of working-class people today who have struggled as the economy has shifted and changed over the years. He said he wrote the book before President Donald Trump’s election in 2016, when the theme of working-class people feeling angry or left behind was a focus.

Lewis said he went to a Trump rally in Bangor to “see what was going on” and found that Maine people there did not seem angry. He chose to make the people in Bealport devoid of anger too, because he thought that was more in keeping with the Maine character.

“In Bealport, anger is not the major issue, the people are dealing with a sense of challenge, of disinheritance,” said Lewis. “They’re more quietly defiant.”

Writing for the New York Journal of Books, Steve Nathans-Kelly said Lewis’s portrait of a down-and-out factory town is “often uproariously and corrosively funny.” David Milch, a former TV colleague of Lewis, who went on to create the cable drama “Deadwood,” called the book “a sharp and fascinating ‘Our Town,’ ” a reference to the classic Thornton Wilder play about a small New Hampshire town.

“I think it’s his best novel,” said Lee Smith, a fellow novelist who also has a summer home in Castine. “It’s a very valuable picture of this moment in time. With the short chapters, from various points of views, the reader becomes a detective, piecing it together.”

Lewis’s father, Richard Lewis, was a producer in the early days of TV with credits that include episodes of 1950s shows like “General Electric Theater,” “Schlitz Playhouse” and the popular Western series “Wagon Train.”

Lewis’s parents divorced when he was young, and he lived in New York state while his father lived in Los Angeles. At a young age, Lewis remembers writing possible stories for TV shows and episodes and sending them to his father, “trying to hold his attention.” They were just a page or two, but his father encouraged him to send more.

He wrote poems and stories in college, at Yale, and had thoughts of starting a magazine. After Yale, he taught English in Greece for a year, then went to Harvard for law school. He still wanted to be a writer, but thought he needed a fallback plan. After law school, he tried to write fiction for a while until he went “totally broke” and took a job in the New York district attorney’s office, working in Manhattan.

He worked there for two and a half years, still writing on the side. And, even if he didn’t know it, watching the daily workings of the criminal justice system gave him lots of ideas for characters and story snippets he’d use later, especially on “Hill Street Blues.”

He moved to California in 1980 to pursue writing and got a job as a paralegal in a law firm while also sending out scripts. About a year later, he landed “Hill Street Blues,” after it had already been on the air for a season or so and had begun to gain critical praise. He went on to work on 84 episodes, more than any writer other than the series’ creators. He won a writing Emmy for the show in 1982 and got an outstanding drama series Emmy in 1984 as one of the show’s producers.

The groundbreaking drama focused on a dozen or more regular characters who worked in a police precinct in a big city, plus all the people they encountered throughout the day. It was an ensemble cast, with no established stars, and new stories every week. During its seven-year run, the show got 98 Emmy nominations. It won eight Emmys in its first season. “We’d have a big chalkboard in the writer’s room, with 15 characters or more, and long stories or short stories connected to them,” said Lewis. “It was pretty complicated. Drama shows didn’t used to be like that; ‘Hill Street’ pioneered that.”

After “Hill Street Blues” finished its run, Lewis worked on a comedy for NBC called “Beverly Hills Buntz.” That show featured “Hill Street” detective Norman Buntz, played by Dennis Franz, moving to California to become a private investigator.

Then NBC network executives asked him to come up with a medical drama, and Lewis created “Lifestories,” a drama that focused on different patients and their challenges each week. Not all episodes had a happy ending. The show lasted one season.

“I think with that show, he predicted what’s happening a lot in TV now, where shows are more meditative and more about real life,” said Epstein.

Lewis said, around this time, he decided he didn’t want to do series TV anymore, and he and his wife, who had been coming to Maine on vacation for years, bought their house in Castine.

Lewis had been coming to Maine off and on since college, when he spent some time with friends in Tenants Harbor. He had a law school friend from Maine, as well, and used to visit with him around Old Orchard Beach and Portland. When he and his wife started looking to buy a house in Maine, a colleague from Los Angeles who had spent some time in Castine highly recommended the seaside town.

Lewis’s first novel, “Meritocracy: A Love Story,” came out in 2004 and opens with college friends from Yale at a Maine summer cottage. The novel is about Lewis’s own generation and the idea of “meritocracy,” which at its more basic core is about people “who have achieved more having more opportunities than people who have achieved less.” Many people use the term to talk about people getting what they earn, while other people use the term to mean a system where the “haves” have the upper hand over the “have nots” because of their education and connections.

Lewis says the idea is much more complicated than that. That’s why he wrote three more novels linked by the same idea: “The Conference of the Birds,” “Theme Song for an Old Show” and “Adam the King.” The four were packaged and sold together at one point as “The Meritocracy Quartet.”

“The notion (of meritocracy) as social theory sort of contrasts with the idea that everyone deserves more or less the same opportunities,” said Lewis. “I did one book for each decade, from the ’60s through the ’90s, writing about my generation, the one that got the benefits of the so-called meritocracy.”

“Bealport” touches on similar themes, as it’s about people in a Maine factory town “who are not necessarily the beneficiaries” of a meritocracy, Lewis said.

The novel begins with characters at a demolition derby, something Lewis had seen first-hand during his years in Maine. He even has a friend who’s a driver.

Other characters and places that pop up in the book include a local surplus and salvage store and the groups of friends who gather at the local McDonald’s for breakfast. Plus the people who work at the factory.

“These are not people who have made out like bandits,” Lewis said of Bealport’s inhabitants. “These are good people who maybe have been left behind a little.”

Ray Routhier can be contacted at 791-6454 or at:

rrouthier@pressherald.com

Twitter: @RayRouthier

Send questions/comments to the editors.