BLESSINGTON, Ireland — When St. John Paul II visited Ireland in 1979, the Catholic Church wielded such power that homosexuality, divorce, abortion and contraception were barely spoken of, much less condoned. Catholic bishops had advised the authors of Ireland’s constitution, and still held sway.

Today, as Pope Francis prepares to visit, the Catholic Church enjoys no such influence.

As once-isolated Ireland experienced a tide of secularism and economic boom that opened it to the world, the church largely lost its centrality in Irish life.

Then the church – while still maintaining a stronghold on education and health care in Ireland – lost its moral credibility following revelations of the widespread sexual abuse of children in its churches, the physical torture of youngsters in its schools and the humiliation of women in its workhouses.

If that weren’t enough, an amateur Irish historian researching the deaths of some 800 youngsters discovered a mass grave in a sewage area at a church-run orphanage where the children had been sent. Their sin for being exiled to the home and buried in an unmarked grave? The shame of having been born to an unwed mother.

Francis will be confronted with that haunting past when he visits Ireland this weekend to close out the Vatican’s big Catholic family rally. The event, scheduled three years ago, had been aimed at boosting the church’s visibility and voice, but a fresh wave of scandal across the Atlantic has overshadowed the visit.

‘NOPE TO THE POPE’

“I have no trouble nailing my colors to the mast that I am a practicing Catholic,” said Carmel Dillon, principal of St. Mary’s junior school in the picturesque town of Blessington, southwest of Dublin. “However, it is becoming more difficult in circles to state that you are a Catholic.”

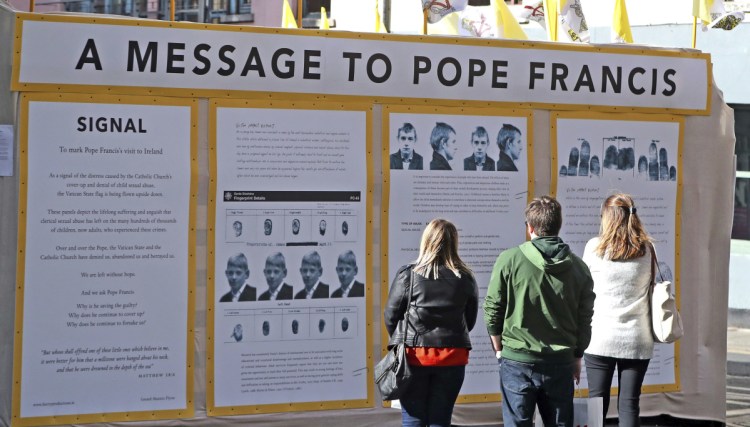

Ahead of the visit, a “Say Nope to the Pope” campaign has attracted a strong following and peaceful protests have been planned. Posters were put up around Dublin featuring an upside-down Holy See flag to “depict the lifelong suffering and anguish that clerical sexual abuse has left.”

Vatican spokesman Greg Burke said Francis knows well that “any trip to Ireland was not only going to be about the family.” But he said family life would still be the focus, even if Francis will be meeting with abuse victims during his 36-hour visit.

Cardinal Kevin Farrell, the Irish-born, U.S.-raised official in charge of Catholic families at the Vatican, said he expected that Francis would speak out about all kinds of abuses suffered by the Irish, including families who lost children during “the troubles,” Northern Ireland’s decadeslong bloody sectarian conflict.

“I do not think that these wounds are easily healed,” Farrell told the AP. “I do think, though, that it’s time for the church once again to make itself known, in a new image of the church. An image that’s more open, more caring, more understanding of the reality of the lives of people today.”

That is not the Catholic Church of Ireland’s past. Over the last 10 years, a series of government-initiated investigations have uncovered the horrific secrets that the Irish church had long sought to bury, like the remains of children at the Bon Secours mother and baby home in Tuam, County Galway.

The reports have detailed how tens of thousands of children suffered wide-ranging abuses in church-run workhouse-style institutions, how Irish bishops shuttled known pedophiles around the country and to unwitting parishes in the U.S. and Australia, and how Dublin bishops didn’t tell police of any crimes by clerics until forced to by lawsuits in the mid-1990s.

The Irish church eventually unveiled a policy requiring the mandatory reporting of all suspected sex crimes to police, but the policy was rejected by the Vatican in 1997. That position, combined with the Vatican’s refusal to cooperate in the fact-finding probes, prompted one of the inquiries to find the Vatican itself culpable in promoting a culture of cover-up.

In response, Ireland’s then-Prime Minister Enda Kenny issued a blistering attack on the Vatican in Parliament in 2011, accusing it of downplaying the rape of children to protect its own power and reputation.

Kenny’s speech, in which he denounced “the dysfunction, disconnection, elitism … the narcissism that dominate the culture of the Vatican to this day,” led to a diplomatic standoff that only really ended when Ireland reopened the Vatican embassy in 2014 after closing it for nearly three years.

A FALL FROM GRACE?

Irish academics see Kenny’s speech as the final nail in the coffin of the once-symbiotic relationship of church and state that had so characterized Irish life.

It was “a moment that encapsulated the fall from grace of an institution which had hitherto been culturally indistinguishable from Ireland as a nation,” according to the 2017 book “Tracing the Cultural Legacy of Irish Catholicism: From Galway to Cloyne and Beyond.”

In the years since Kenny’s speech, Irish voters have overturned the country’s constitutional ban on abortion and legalized same-sex marriage. And in the years after John Paul’s 1979 visit, Ireland decriminalized homosexuality and legalized contraception and divorce.

And while Dublin Archbishop

Diarmuid Martin has won plaudits from sex abuse survivors for spearheading the cleanup of the Irish church, survivors want Francis now to atone for the Vatican’s sins in the cover-up.

Francis needs to “admit and acknowledge and own the fact that the Roman Catholic Church at the global level, directed by the Vatican, has covered up the crimes of priests,” said Colm O’Gorman, an abuse survivor who is leading a rally Sunday with other victims and supporters.

But sex abuse survivors are not the only ones demanding accountability – or at the very least a word of regret – from the pope.

Catherine Corless, whose research into the deaths of some 800 children at the Tuam orphanage pointed to the mass grave, is seeking an apology for the survivors and their families, many of whom are still church-going Catholics.

“They’re not asking for much,” she told the AP. “It would mean so much for the church to say ‘What happened was wrong.’ “

Send questions/comments to the editors.