WELLS — A loud and broken Leonard Cohen “Hallelujah” to Joan Silverman for her July 1 Maine Observer essay, “Emily Post, my mother and me.” Silverman notes, “There’s a case to be made for profanity.” Thanks to a courageous journalistic decision made by the Portland Press Herald almost 40 years ago, I can lend evidentiary support to Silverman’s pointing to “the value of learning how and when to use irreverent language.”

In 1978, when my daughter Summer was 8, she tearfully reported that she and her brother JP, then 11, had gotten into a verbal confrontation. When I asked about her role in the altercation, she said, “I called him a ‘fatso.’ ”

Now I was really worried, and not just because JP was almost anemically rail thin at that time. I also pondered how this precocious 8-year-old could express the heights of her tear-stained anger with the unbelievably mild as well as inaccurately descriptive “fatso.”

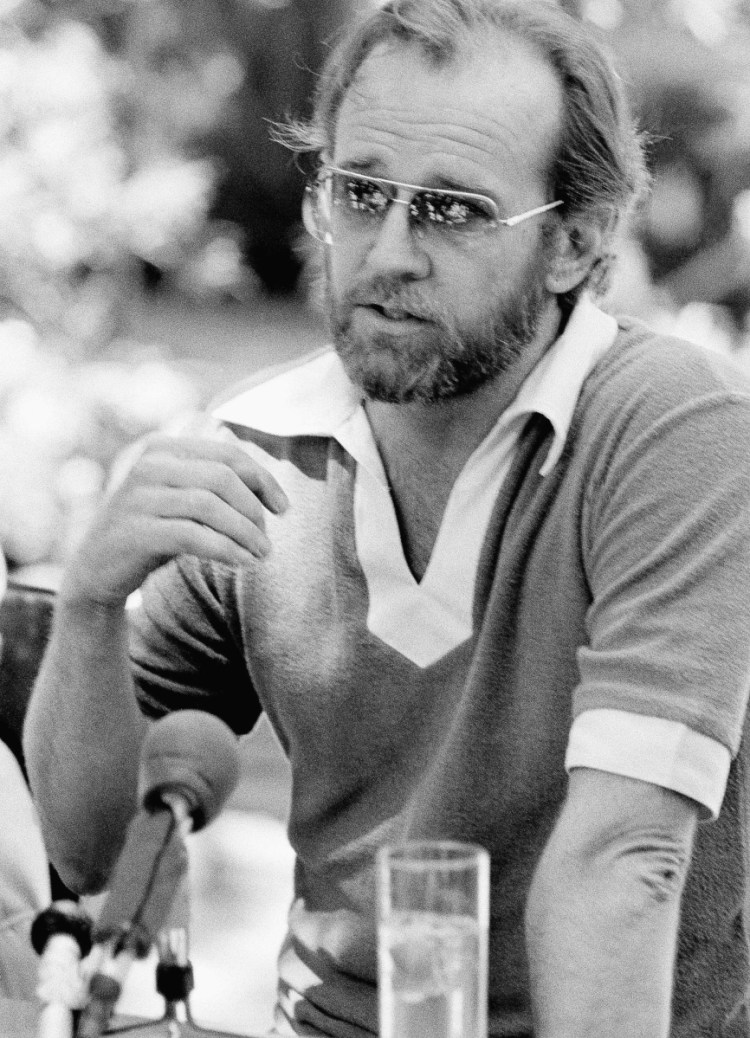

ENTER GEORGE CARLIN

Help soon arrived. That summer, the U.S. Supreme Court announced its decision in FCC v. Pacifica, concluding that the Federal Communications Commission had the constitutional authority to discipline a Pacifica Radio station for playing a recording of George Carlin’s “Filthy Words” monologue during the day when children might be listening. In Carlin’s piece, he sarcastically and comically comments on the seven words one cannot say on the public airwaves. Today’s curious reader can simply go to the internet to see Carlin’s pick for the Dirty Seven, but that option did not exist in 1978.

Much to its credit, the Press Herald reported on the case but did not print the seven dirty words. The newspaper did convey, however, that readers wanting to receive a copy of the list merely had to write to the paper and request it.

This then became a project for Summer and an ethical test of the resolve of the local newspaper. Would the paper deliver on its promise? With my urging, and in the careful and deliberate style of an 8-year-old, Summer sent her request for the list to the newspaper.

A few days later an envelope arrived addressed to her. In clear and unambiguous prose were the magic seven. I did not immediately know whether or not this lesson had helped Summer.

Fast forward 10 years. I am enjoying listening for the first time to a recording of a collection of songs Summer made for my birthday. The collection consists of old selections Summer knows I like and newer ones she thinks I will like. Toward the end of the recording, evidently made in her room at the State University of New York at New Paltz, among her friends, is a telling exchange.

GOING BEYOND ‘FATSO’

Her friends knew Summer was recording the songs for her father and, in good fun, wanted to set a trap for her. Because the recorder was being switched on and off according to whether or not the music was appropriate for inclusion, her friends attempted to draw Summer into a conversation when she was not aware that the recording device has been switched on. You know the routine: Secretly flip on the recorder, ask a friend about the last time he or she got wasted on beer or pot and then jokingly threaten to send the recording home in a “gotcha” moment.

Her friends, however, couldn’t catch Summer off guard. She repeatedly discerned what they were attempting and consistently asked them to turn off the recorder rather than responding to questions they meant to be embarrassing if not incriminating. No doubt, she was silently mouthing appropriate swear words while she was beseeching them to “turn off” the tape, but this just encouraged them to persist in trying to catch her in an unguarded moment, perhaps one where she even used damning profanity.

Finally tiring of this ruse, Summer had the last words. I still cherish listening to the songs on the recording, but my favorite part remains its abrupt ending. After repeated urgings to her friends to turn off the device, Summer effectively succeeded with the final words, slightly laundered here, “Turn off the f — in’ tape.”

George Carlin could not have said it better. Summer had effectively enriched her verbal repertoire beyond “fatso.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.