Let us now praise ordinary fathers, ones who don’t constantly smoke and drink, or French-kiss their daughters, or pound the table while yelling, “Everyone shut up but me.” An ordinary father who watches his daughter receive her diploma from Harvard instead of hanging out with the Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. One who doesn’t show off “his cute teenage daughter” at discos.

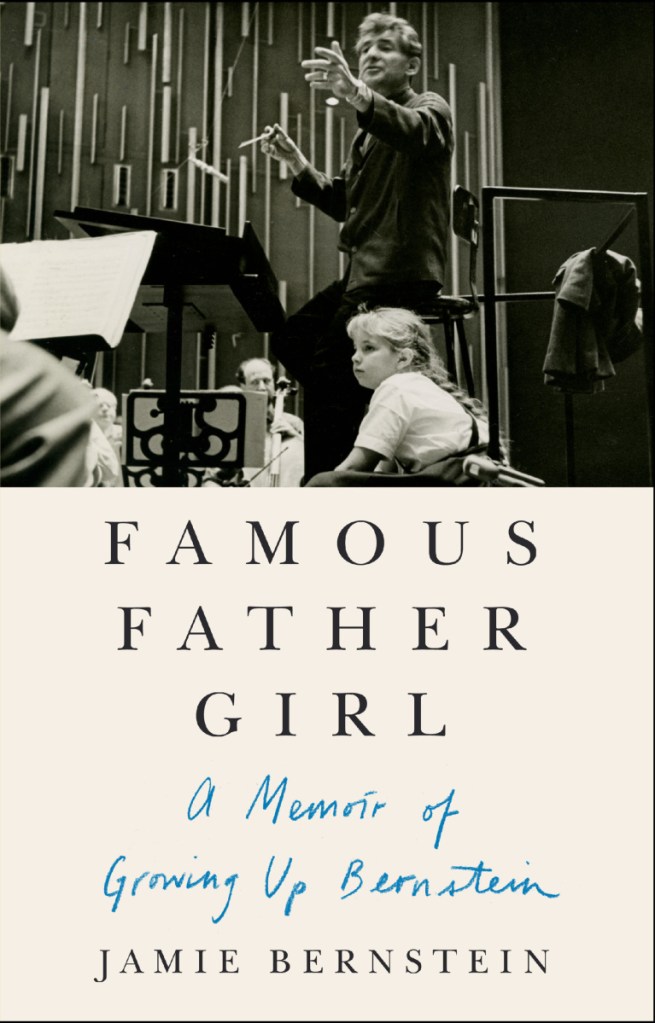

But ordinary fathers rarely become global cultural heroes or change how orchestral music is received by the masses. In “Famous Father Girl,” Jamie Bernstein’s memoir of her father, conductor-composer Leonard Bernstein, we learn that she “longed to be like the ‘normal’ people we saw on TV,” despite loving the “raucous, confusing world” of her parents. At the center of this world stands her father, a compelling mix of intellect, warmth, charm, sexiness and immense energy. Seduction might have been his greatest talent, one countered by his daughter’s aptitude for truth-telling. Her memoir portrays a man whose weaponized ego fits perfectly into American celebrity culture, but it’s also a story of how his daughter survived that ego to become her own woman, even as she remains intent on keeping her father’s legacy alive.

Between 1943, when he made his conducting debut with the New York Philharmonic, and his death in 1990, Bernstein was never out of the public eye. But at home he’s not always a glamorous figure: Jaime remembers him sitting at the breakfast table smoking and farting. The constants of Jamie’s childhood were “a bluish haze of cigarette smoke,” the clink of late-afternoon ice cubes, household servants, word games, and frequent parties attended by artists and intellectuals. Everybody loved Lenny – as he was known to his friends and family – none more so than Jamie herself. Singing, playing and exchanging numerous hugs with him created a strong bond between them. But even her sunniest memories are tempered with shadows.

As Jaime moved from childhood into adulthood, navigating her father’s exhibitionist tendencies became a challenge. Jamie’s telling omits the yuck factor, so prominent in “Priestdaddy,” Patricia Lockwood’s recent memoir about her eccentric father, a priest by papal dispensation. Bernstein offers instead a one-size-fits-all explanation for her father’s exuberance: It was just the way he was. Describing a dinner with a Russian actor, for example, she writes that her father kissed her “fully on the lips, then [pushed] his tongue into my mouth. Daddy tried this tongue-kissing stunt on almost everyone, usually late at night, after much drinking (and possibly an orange pill).” Though his actions embarrassed and sometimes hurt her, she’s reluctant to fully consider their implications. At her 28th birthday party, before a group of people, Bernstein “gestured to a crease in his forehead and said to [Jamie,] ‘You see this line here that runs right down the middle? That’s the Line of Genius. You don’t have one.'” Assessing this humiliation, Jamie simply writes that “it did seem unusually mean.”

Thinking more deeply about her father’s behavior might lead to unpleasant conclusions, and though Jamie denies there was any abuse, she writes that “it was hard not to feel my father’s sexuality. … Everybody felt it. Tricky stuff for a daughter.”

Though we may wonder about Jamie’s generosity toward her father, her brother, Alexander, had no difficulty directly expressing how he felt about his father’s controlling nature. In Jaime’s account, during a party to celebrate Alexander’s graduation from Harvard, a school Bernstein insisted his son attend, guests found his diploma “impaled on the front door with a kitchen knife.” This is just one of many punchy details in the book that reveal the ugly reality of what Jaime calls “the Lenny Show.”

Tentative as Jamie is about her father’s excesses, she is fiercer still in defending him. She explodes at Tom Wolfe’s treatment of her family in his article “Radical Chic,” which mocked the cocktail party/fundraiser her parents hosted for the Black Panthers in 1970. Though she was not at the party, Jamie remains enraged over Wolfe’s article and the damage it caused the family. Her mother was particularly wounded.

“Famous Father Girl” is a good book that strives to keep Leonard Bernstein before the public eye. Short on psychological insight, it is long on love and acceptance: love for a father of boundless energy and acceptance of one who sometimes crossed boundaries a father shouldn’t cross.

Send questions/comments to the editors.