Minerva Milk, mother of the late, transformative gay icon and politician Harvey Milk, believed deeply in the precept of tikkun olam, the Jewish obligation to repair the world. An early feminist who, with her husband, had raised Harvey and his older brother on Long Island, “Minnie,” as she was known, succumbed to a heart attack in 1962 while delivering a 24-pound turkey on Thanksgiving to the poor on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

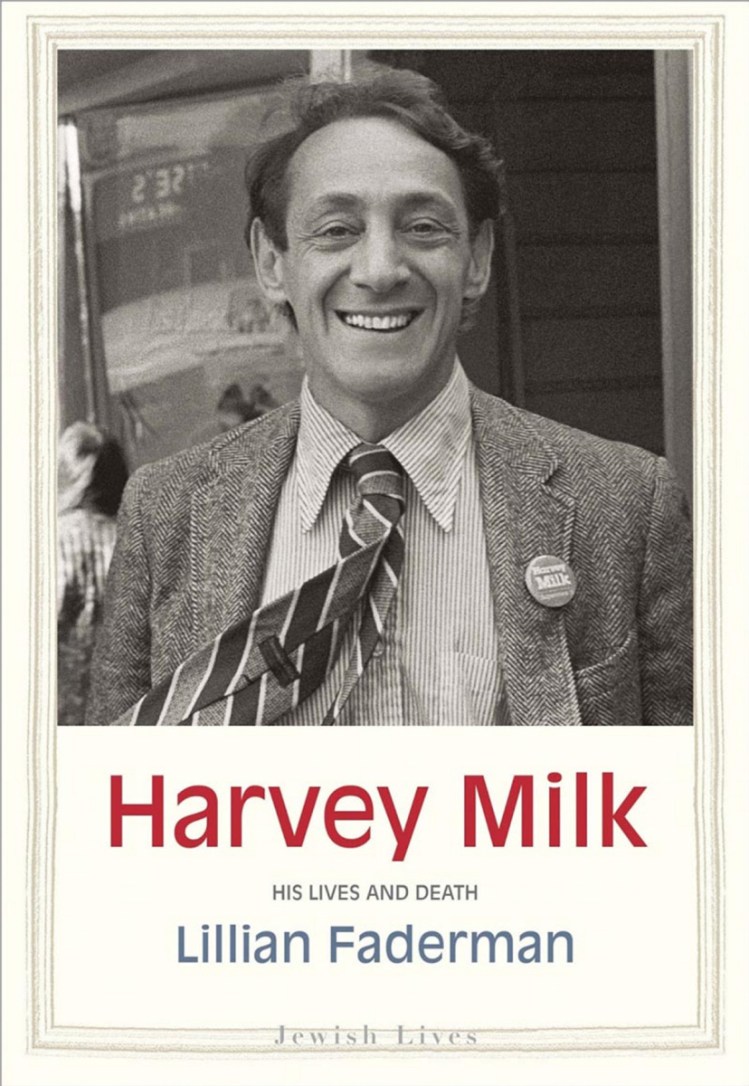

This trenchant familial story appears early in “Harvey Milk: His Lives and Death,” the latest installment in Yale’s “Jewish Lives” series – individual biographical volumes that explore Jewish identity. Author and lesbian historian Lillian Faderman thus lays a compelling foundation for building our understanding of Milk’s life on how Yiddishkeit – Jewish customs and culture – informed his relentless quest, as he implored, to “burst down those closet doors once and for all.”

Faderman’s exploration of Milk’s dual outsider status as gay and Jewish is equal parts warm and scholarly. It is informed, in part, by her decades of research and writing about LGBT history, including, most recently, her book”The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle.” Her empathy may also come from firsthand experience with the after-effects in those touched by the Holocaust. Faderman’s mother and aunt had escaped Nazi Europe to America; tragically, many others in her family perished in Latvia. Milk, too, had been deeply affected by his memories of the war.

As Faderman relates in “Harvey Milk,” just days before his bar mitzvah, Milk and his family huddled by their radio to learn the fate of the Jews of Warsaw in 1943. Living on Long Island, which was rife with anti-Semitism at the time, Milk, like many Jewish children, feared that the same brutal circumstance could reach him in America. “He imagined himself as a resistance fighter, battling to the death though besieged. … When he became a politician, the trope he used over and over again in his speeches – to warn gay people about what could happen if they did not defeat their enemies – was the Holocaust.”

The book follows Milk from those early days, past his time as a closeted, butched-up jock in high school and college, through his period in the Navy, and to his years of ambivalently holding jobs as a math teacher and a Wall Street securities research analyst. Faderman then carries readers buoyantly through Milk’s emerging devotion to social justice and progressive politics as he holds court as a bearded hippie and the self-proclaimed “Mayor of Castro Street” in his beloved adoptive city of San Francisco.

Having periodically voiced the premonition that his life would be violently cut short, Milk was on a mission to improve the welfare of gay people, as well as all others who were disenfranchised or in the underclass. As Faderman points out, “He was very aware of himself as part of an ultraliberal Jewish tradition that fought for the oppressed of all stripes.” In taut, brisk prose that mirrors his sense of urgency, she relates how Milk’s relentless pursuit of his own version of tikkun olam involved three failed runs for office as an openly gay man in San Francisco during the tumultuous gay liberation movement of the 1970s. At that time, the city’s homophobic police variously entrapped, jailed and beat the rapidly multiplying population of gay men who chose San Francisco as their mecca.

As Milk foresaw, he was tragically assassinated, in 1978 at age 48. It was a year after he triumphantly won a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and became one of the first openly gay men elected to office in America. In addition to drawing from what is perhaps the essential biography of Milk, Randy Shilts’ “The Mayor of Castro Street,” Faderman further informs her considerable knowledge of that time and place in LGBT history with background interviews she conducted with some of Milk’s relatives, who shared unpublished documents, and with comrades who took up the fight for gay liberation alongside Milk. The latter include conversations with his mentee, Cleve Jones, creator of the AIDS Quilt, and Anne Kronenberg, who was Milk’s campaign manager during his historic campaign for supervisor.

Faderman punctuates her telling of Milk’s story with vignettes that add a richness to the portrait of his romantic life. Insatiably sexual, he was also a highly domesticated romantic. For example, he gave a gold Chai to his beloved Scott Smith, who was not Jewish. Describing the piece, Faderman writes, it was “two attached Jewish letters, chet and yod, whose numerological significance symbolizes ‘life.’ Scott wore it for a while on a chain around his neck. It seemed to say that now they were truly one.” When Smith and Milk had difficulty floating their business, a neighborhood camera store that also functioned as Milk’s de facto campaign headquarters, Faderman observes, “If they did not have the money to eat the best, [Milk] liked to say, they could always eat eggs scrambled in matzo brei.”

Then there are the stories Faderman shares of his kibbitzing with his constituents – Teamsters-backed truck drivers, housewives, racial minorities, the disabled. Among them was Henrietta Abrams, an elderly Jewish woman who, with homemade treats in tow, would visit Milk at City Hall. “They would sit together in his office, door closed, their chitchat interspersed with bits of Yiddish, and munch cookies. She called him ‘her little Jewish prince.'” Such sketches, each incidental in isolation, come together to render the portrayal of a man, who, while not observant – Milk detested organized religion – reveled in the trappings of cultural Judaism.

Milk is famed for peppering his fiery soapbox-style political speeches with references to hope. “You … have got to give them hope!” It’s a principle notably derivative of one in the Old Testament’s Ecclesiastes: “Where there’s life, there’s hope.” Harnessing her perspective as a lesbian scholar and Jew born in New York City just a decade after Milk, Faderman’s sensitive contextualization of his life illuminates that his great humanity, as well as his successes and failures, were very much entwined with his Jewish identity.

Send questions/comments to the editors.