WASHINGTON — The Senate passed its version of the $428-billion farm bill Thursday, setting up a bitter fight against the House over food stamps, farm subsidies and conservation funding.

The vote was 86-11, an overwhelming majority that reflected a bipartisan desire to rush relief to farmers confronting low food prices, rising suicide rates and an array of other troubles. But the lopsided vote belied the challenges that may await when lawmakers meet later this summer to reconcile the gaping differences between the House and Senate bills.

Chief among these: The House version of the legislation, passed narrowly last week with no Democratic support, imposes strict new work requirements on many able-bodied adults before they are permitted to receive food stamps. The Senate version, which needed Democratic votes to pass, does not include major changes to food stamps.

Key senators have said they would not support a final bill containing work requirements, even though that policy is backed by the White House, because it would jeopardize the bipartisan support the legislation needs to pass. The Senate farm bill also preserves a major conservation program gutted in the House bill, and includes a measure, unpopular in the House, that would limit farm subsidy payments.

With House Republicans insisting they’ll fight for their version of the legislation, the discrepancies have fueled fears Congress will not be able to pass a new farm bill before the current law expires Sept. 30. That could cause major disruptions in some programs, unless lawmakers extend the current legislation or appropriate separate funds.

With farmers already struggling with low commodity prices and market jitters over President Donald Trump’s tariff threats, farm-state senators of both parties stressed ahead of Thursday’s vote that the legislation’s passage was crucial.

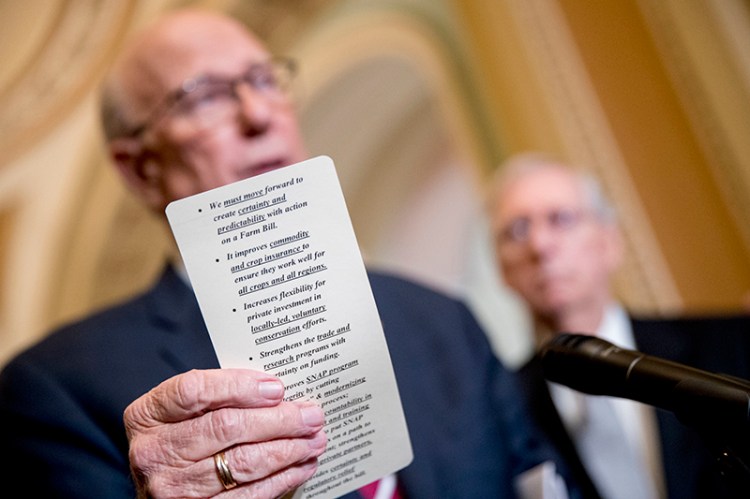

“I don’t know how I can emphasize this more strongly, but I hope my colleagues will understand that the responsibility, the absolute requirement, is to provide farmers, ranchers, growers – everyone within America’s food chain – certainty and predictability during these very difficult times that we’re experiencing,” Agriculture Committee Chairman Pat Roberts, R-Kansas, said on the Senate floor.

“This is not the best possible bill. It’s the best bill possible. And we’ve worked very hard to produce that,” he added.

Farm income has dropped in each of the past four years as commodity prices have fallen. Slightly more than half of all farms now lose money each year, according to the Department of Agriculture — a predicament that is expected to worsen as the Federal Reserve raises loan interest rates and trade tensions threaten export markets.

“There is a sense of urgency in the country. There are so many things right now that are up in the air for farmers and ranchers. It’s a very, very difficult time,” said Sen. Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., the top Agriculture Committee Democrat. “And this bill really is a bill that provides a safety net for farmers and a safety net for families.”

A massive legislative package that oversees a range of farming, conservation and nutrition programs, the farm bill is reauthorized every five years — generally on a bipartisan basis. Separate bills work their way through the House and Senate before lawmakers reconcile them in conference. The compromise bill must then pass each chamber again before heading to the president’s desk.

This year bipartisan negotiations fell apart in the House as Republicans embraced food stamp work requirements bitterly opposed by Democrats. The House farm bill also became briefly ensnared in an unrelated legislative brawl over immigration, which caused it to fail on the first try before passing — barely — when it was brought back up last week.

Under the controversial House food stamp plan, most adults would have to spend 20 hours per week either working or participating in a state-run training program to receive benefits under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which provides an average payment of $125 per month to 42.3 million Americans. While both the White House and House Republicans have pitched the plan as an inventive way to get people back to work, House Democrats and Senators in both parties have vowed to vote against a plan some say will unfairly increase red tape for low-income Americans.

An attempt by Republican Sens. Ted Cruz (Texas) and John Kennedy (La.) to add tougher food stamp language to the Senate version of the bill failed Thursday as 68 senators voted to table their amendment while only 30 supported it.

“The things that they have in there are mostly to hassle people that are on SNAP. That’s really what it’s about,” Rep. Collin Peterson, D-Minn., top Democrat on the House Agriculture Committee, said Thursday of the food stamp provisions in the House bill. “Like I told people, the only thing that’s going to work that’s going to be developed out of this farm bill is paperwork.”

But House Agriculture Committee Chairman Michael Conaway, R-Texas, said he would defend the provisions during conference committee negotiations, arguing it would be bad politics in an election year for lawmakers to oppose changes aimed at moving people into the workforce.

“I do expect that having this conversation with the American people just ahead of the election that says if you’re work-capable, 18 to 59, and you want SNAP — and you’re not mentally or physically disabled, you’re not a care-giver of a young child — that you just split the program by working 20 hours a week and/or participating in an education training program that gets you there – that’s a winning argument across every demographic in this country,” Conaway said. “If our colleagues are that far out of step with what their voters are telling them just before the election, then they may be doing that at their own peril.”

Lawmakers also anticipate a battle over the Senate’s proposed changes to farm subsidies and crop insurance, two components of the roughly $13 billion federal farm safety net. Under the Senate bill, farm “managers” who are not actively engaged in running a farm would lose out on the subsidy checks USDA distributes when crop prices fall below predetermined references.

That stands in stark contrast to the House bill, which raises existing limits on crop subsidies. Conaway said that given the troubles afflicting farm country, “going after the safety net at this stage – maybe it was a better idea in 2014, but I think it’s a terrible idea for 2018 given the backdrop.”

Lawmakers are also likely to clash over conservation funding, which both chambers reduced — but which the House cut more steeply, by $5 billion over 10 years. House Republicans have proposed eliminating much of the Conservation Stewardship Program, a popular initiative aimed at encouraging farmers to address soil, air and water quality.

Smaller conflicts could also emerge around popular programs that promote organic agriculture and local foods, which received mandatory funding in the Senate but were left out of the House bill.

“There are always differences, but this level of difference is not typical,” said Ferd Hoefner, a long-time strategic advisor to the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. “It’s the result of the decision in the House to pass a partisan farm bill, without considering some of these other issues and programs on a bipartisan basis at the committee level.”

Congress could extend the current farm bill, if lawmakers are ultimately unable to iron out those differences. Without an extension or a new bill, the current law will expire on Sept. 30, causing some programs to lose funding.

But lawmakers are under enormous pressure from farm groups, including the powerful American Farm Bureau Federation, to pass a bill on time, giving farmers more certainty in the upcoming growing season. That pressure may ultimately force both sides to make concessions in conference.

“There’s no reason for us not to get a conference done and a bill back through both chambers by deadline,” said Andrew Walmsley, the Farm Bureau’s director of Congressional relations. “We do not want to see an extension.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.