In early 1981, midway through the third season of ABC-TV’s hit series “Mork & Mindy,” an episode titled “Mork Meets Robin Williams” revealed its newly, drastically famous co-star’s conflicted feelings about being famous.

Williams, then 29, played a resident of the planet Ork, confounded by the ways, means and hang-ups of earthlings. In this episode, he also played himself. The show was like a therapy session. Williams as Williams spoke of the appeal of pretending to be someone else; “characters could say and do things,” he said, regarding his younger self, “that I was afraid to do myself.” Williams as Mork closed the show with a report back to his home planet. He puzzled over how “everybody wants a piece of you” if you’re famous and marveled pityingly at the “responsibilities, anxieties” and the “very heavy price” paid by everyone from Marilyn Monroe to Jimi Hendrix to John Lennon, a recent casualty.

He didn’t add “Robin Williams” to that list, but the episode, in effect, wrote the star’s name in invisible ink.

Williams went from mad, whirling stand-up comic to TV star to movie star in what seemed like a flash. Stardom, its rises and falls and demands, intertwined with Williams’ struggles with alcohol and drug addiction. His family lives and marriages were overlapping, fairly complicated, often difficult matters. His interior life remained a partially closed door to even his closest friends and relations.

And then, in Tiburon, Calif., in 2014, at age 63, he hanged himself. The brain disorder plaguing Williams at the end went misdiagnosed for years. His life was one of compulsive creativity and genuine kindness and perpetual insecurity and frequent infidelity and uniquely electric imagination.

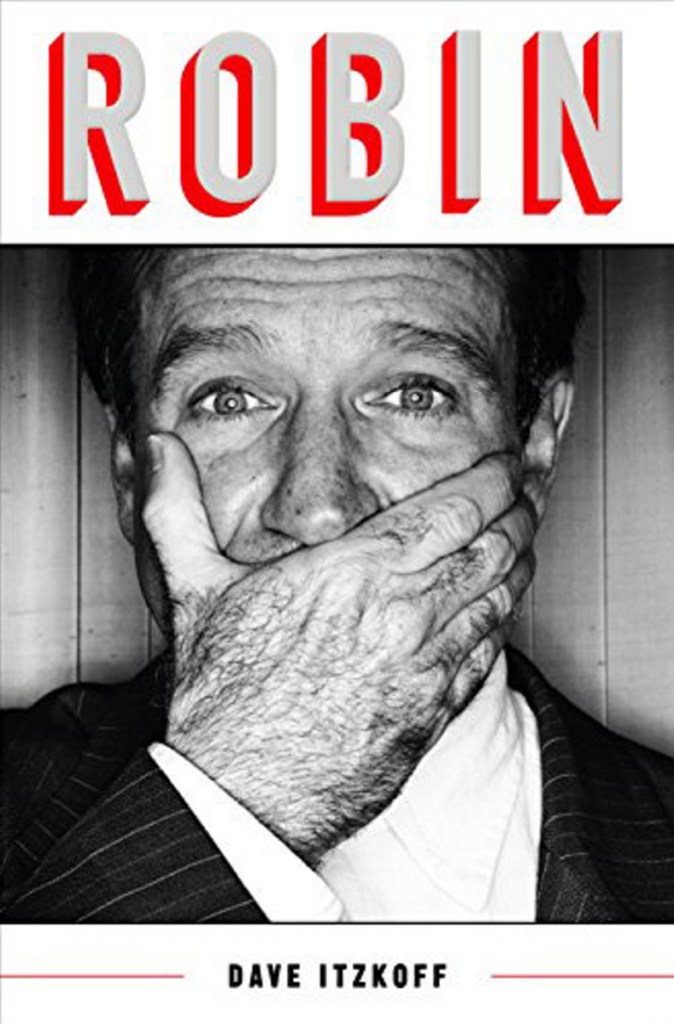

Dave Itzkoff’s biography “Robin” gets its hands around as much of that life as possible. It’s an incisive, comprehensive, very fine book. Itzkoff, a longtime New York Times culture reporter, profiled Williams for the Times in 2009, after Williams underwent heart surgery and launched his “Weapons of Self Destruction” comedy tour. Out of that piece, Itzkoff pitched and sold a full-length assessment of a star who was a planet, an Ork, unto himself, forever orbiting his own complicated fame.

Born in Chicago, Robin McLaurin Williams spent a childhood zigzagging around Illinois and Michigan. His father, Rob, worked for Ford; his mother, Laurie, met Rob when she was modeling for the Marshall Field’s department store. Rob had sons from a previous marriage. Laurie had a son from her own, brief first union. Later, his half-brothers became part of young Robin’s life, inconsistently but fondly.

He spent a lot of time alone. Itzkoff writes cogently and well about young Robin’s years in the posh northern Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills, in a mansion with the Brontesque name of Stonycroft. The attic was his playground. He played with battalions of toy soldiers; he practiced his TV idols’ stand-up routines. If Jonathan Winters came on “The Tonight Show,” then hosted by Jack Paar, Rob and Robin stayed up late to watch. “Seeing my father laugh like that,” Williams later said, “made me think, ‘Who is this guy, and what’s he on?’ ” He spent the rest of his life trying to answer those questions, by way of his own blinding talent and in the grip of his own compulsions.

Relocating to the Bay Area, the Williams family adjusted to Tiburon, Calif. Robin attended Redwood High, and for an awkward time, among the tie-dye and hippie holdovers, he dressed the same way he did back at tony, stuffy Detroit Country Day. At Claremont Men’s College east of Los Angeles, Williams took an improv class taught by Dale Morse, formerly of San Francisco’s influential comedy troupe The Committee. His first troupe was called Karma Pie. He did summer theater here and there, from Shakespeare to “The Music Man” (he played Marcellus, the “Shipoopi” guy). He also did Brecht and Ionesco.

Williams was accepted into Juilliard in 1973 in New York City, where he met Christopher Reeve, who became a good friend. He did mime in Central Park, and anyone who did needed all the friends he could get. An early performance partner, Todd Oppenheimer, is quoted in Itzkoff’s book as appreciating the eager, malleable Williams: “(W)e could at least commiserate with each other when people walked away,” he says.

Then, after honing his stand-up and ingesting a lot of cocaine in San Francisco, Williams hit Los Angeles in 1976. It didn’t take long for word to get around. Stand-up led to “Mork & Mindy” (though creator Garry Marshall initially envisioned John Byner or Dom DeLuise or Williams’ idol, Jonathan Winters, in the Mork role). Fame and its discontents pulled him along. “Popeye,” that bizarre folly (a key film in young Itzkoff’s life, we learn), gave Williams his first starring role on screen, though he really didn’t pop until seven years later, when director Barry Levinson shaped “Good Morning, Vietnam” around his prodigious skill set.

Between his best-selling comedy albums and his biggest early film successes, Williams fans grew to expect a certain kind of funny, the kind nobody can sustain or grow older doing without becoming a Robin Williams impersonator. He scored three Oscar nominations, prior to his supporting actor win for “Good Will Hunting,” with material that allowed him some interpretive leeway: “Good Morning, Vietnam,” followed by “Dead Poets Society,” followed by the more manic Terry Gilliam fantasy “The Fisher King.” He had his most popular top-line showcase in “Mrs. Doubtfire” and killed as the voice of the genie in “Aladdin.”

But he had a well-known and oft-derided treacle problem. Mechanical heartwarmers, such as “Jakob the Liar” and “Patch Adams” and, much later, miserable comic vehicles such as “Old Dogs” and “License to Wed,” were just asking for it. He lived with various demons; when Jim Carrey burst on the scene, he found himself thinking about him a little too much, and too competitively. He fell off the wagon after nearly two decades of sobriety. He reconfigured his domestic life frequently. “It was how Robin had been taught to live since childhood,” Itzkoff writes: “nothing is permanent, transition is constant. Anywhere can be home and anyone can be family, and you can always start over again in new places, with new people.”

It’s a fascinating life, and the author captures it with grace and evenhanded perception. Through the lens of the post-Weinstein #MeToo era, some of Williams’ antics look pretty sleazy; without rancor, Williams’ “Mork & Mindy” co-star Pam Dawber recalls putting up with a fair amount of butt-grabbing for laughs. Already, these hit-and-run harassments have stolen some attention away from everything else in the book.

The end, of course, is crushingly sad. Misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s, Williams was in fact suffering from Lewy body dementia. The symptoms include Parkinson’s-like tremors, depression and hallucinations. When Williams was finishing up work as Teddy Roosevelt in the third and final “Night at the Museum” picture in Vancouver, a colleague suggested he stop in at a comedy club and try some stand-up. “I don’t know how to be funny,” he answered.

“Think of it this way,” his Comic Relief cohort and longtime friend Billy Crystal tells Itzkoff, “the speed at which the comedy came (to him) is the speed at which the terrors came. … I can’t imagine living like that.” And neither could Williams.

Itzkoff’s previous books include a coming-of-age memoir “Lads” (2004); a book about his father’s addictions (“Cocaine’s Son,” 2011); and “Mad as Hell” (2014), on the making and meaning of “Network.” “Robin” reads smoothly and eloquently, though you wouldn’t mind a few more passages where Itzkoff’s critical intelligence takes off and leaves the organized, orderly reporter behind for a while. Biographies of famous funny people are funny that way: They require both kinds of writers. At his best, Itzkoff is both, and “Robin” is all the better for it.

Send questions/comments to the editors.