Ray Stevens, by any measure, is a successful man.

His 35-page curriculum vitae brims with decades of scientific accomplishment, dozens of publications and book chapters, cutting-edge research institutes he founded as far afield as Shanghai, a doctorate from the University of Southern California and a postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard.

But look more closely and you’ll see, atop his long list of awards and honors, this: “Student/Faculty Research Summer Program Support Award, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Summer/Winter 1984 and Summer 1985.”

That’s where John Ricci, professor emeritus of chemistry at the University of Southern Maine, comes in. The same John Ricci who, more than 30 years ago, couldn’t figure out what Stevens needed more – a pat on the back or a kick in the keister.

Turns out he needed both.

“Fear,” said a smiling Stevens, now 54, when asked to describe his relationship with the professor to whom he owes so much. “I was always, I have to say, extremely nervous, always sweating, whenever I would stand outside his office.”

At its best, education is about relationships. A teacher sees something in a struggling student and, rather than scribbling “F” on an exam and moving on, doubles down on potential unfulfilled.

And the student, for reasons he can’t quite comprehend, keeps coming back, keeps asking for another chance, keeps trying.

On Friday, at USM’s Science Building in Portland, teacher and student met once again to celebrate the 10th year of the John Ricci Undergraduate Fellowship. Founded by Stevens, himself now a professor at USC, it’s both an investment in the future and homage to his past.

“What John did for me, I wanted to see if I could do for others,” Stevens said. Without Ricci, “my life would have been very, very different.”

Stevens arrived at USM in the fall of 1981, fresh out of Edward Little High School in Auburn,

His father, a military man, had died when his son was only 6. His mother, who lost and then regained custody of Stevens and his two siblings during the 1970s, worked two jobs just to keep the family afloat.

Stevens was a computer geek. He still remembers, long before the internet’s arrival, sneaking into a basement at Bates College and hacking into its mainframe – not to be malicious, but because computers were a blast.

He started USM as a computer science major. But then he took an introductory chemistry course taught by professor Ted Sottery and something clicked.

“He was your absolutely typical geek-nerd scientist. He had a big old pocket protector. He had a TI-45 – you know, one of those Texas Instruments (calculators) – in his pocket,” Stevens recalled with a smile.

But Stevens’ most vivid memory of Sottery, who died last year at the age of 90, was that “he was just having fun. It was infectious.”

Stevens changed his major to chemistry. And Ricci, who’d come from Williams College to USM in 1981, became Stevens’ faculty adviser.

To Ricci, the young student posed a bit of a puzzle.

“Things he liked doing, he excelled in,” said Ricci. “And others, I guess he just blew off.”

Take organic chemistry, for example. Stevens took it his sophomore year and got a C-minus. To qualify for his degree, he had to score no lower than a C.

So, he took the course again his junior year and, alas, got a D. Then again in his senior year, when he flunked outright.

The problem: The more he took the course, the less Stevens bothered going to class. In fact, the third time around, he skipped not just the classes, but also the final.

“I wasn’t your model student,” Stevens admitted.

Still, despite his aversion to all organic chemistry, Stevens had that spark, that passion, that was not lost on his academic adviser.

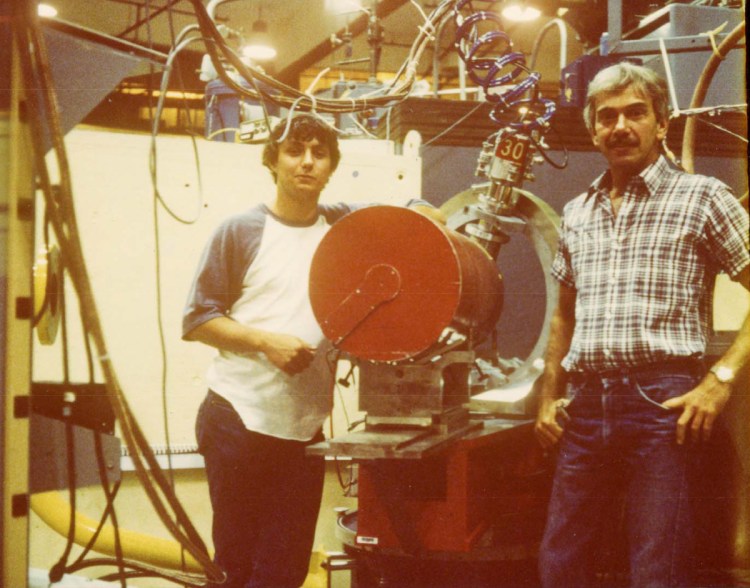

For years, Ricci had spent summers at Brookhaven National Laboratory, a research facility run by the U.S. Department of Energy at a former Army base on New York’s Long Island. He often recruited a student to tag along as his research assistant and, in 1984 and again in 1985, he offered the slot to young Stevens.

To this day, Stevens can still smell the alchemy of “pipe smoke and organics” that permeated the lab. He can still see the nuclear reactor, with which he spent weeks running experiments.

He was hooked.

“Going to Brookhaven that summer completely changed my life,” Stevens said. “It opened my eyes to being able to play with these giant scientific toys and I just thought it was so cool.”

Still, he had that organic chemistry blemish on his transcript. What’s worse, in the second semester of his senior year, Stevens flunked Ricci’s advanced inorganic chemistry course.

The memory still pains Ricci: “It was the hardest grade, the most thinking I had ever done about assigning a grade. Very, very difficult. But I just could not, in any kind of conscience, give him anything but an F.”

After the final exam, Ricci summoned Stevens to his office. He handed Stevens the F – and then gave him hell.

“I shut the door and I really let him have it,” Ricci said. “I was very, very angry and upset. Disappointed. I felt that it was something that was done to me. I internalized the whole thing. Now, not only had he failed my course, but he couldn’t graduate.”

Stevens had already been accepted to graduate school at the University of Denver. With Ricci’s help, he persuaded the school to delay his admission until the following January – in the interim, he would retake organic chemistry over the summer at the University of Maine at Orono and then retake the advanced inorganic chemistry class that fall in Denver.

He aced both courses.

Stevens eventually transferred to USC, where he went on to earn his doctorate in organic chemistry, of all things.

“Very ironic,” he conceded.

From there, he became a professor at the Scripps Research Institute, a biomedical research and education facility in La Jolla, California.

He went on in 2012 to found the iHuman Institute at ShanghaiTech University in China, where researchers are hard at work developing breakthroughs in high-resolution imaging of the human body.

Two years later, he also founded the Bridge Institute at USC, which works across disciplines in medicine, science, engineering and even the arts to advance the diagnosis and treatment of a host of human diseases.

Stevens’ latest vision: A “whole-body scanner” that will detect such afflictions as cancer, multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s long before they become symptomatic and, in the process, enhance both treatments and prognoses.

How soon might we see this?

“Five years,” he replied matter-of-factly.

Not bad for a kid who once was on the verge of flunking out of USM. A student-turned-professor who, 10 years ago, created the annual fellowship in the name of his mentor so that he, too, might take promising students under his wing like Ricci once did for him.

So far, 11 fellows from USM have joined Stevens for an all-expenses-paid summer of hands-on science – first at Scripps and now at the Bridge Institute. In selecting the winner each year, he looks beyond the grades for that excitement, that fervor that Ricci helped ignite in him.

“If you have passion, you can do anything,” Stevens said. “You can learn anything.”

Ian Slaymaker, USM Class of 2007, has that passion. Upon being passed over for the inaugural Ricci fellowship in 2007, he immediately appealed to Stevens.

“Within minutes, (Slaymaker) emails me and he says, ‘I’m really disappointed that I didn’t get it. Would you be willing to take me in if you didn’t have to pay me and I’d just live in my car outside the lab for the summer?’ ”

“That’s passion,” said Stevens, who decided on the spot to host two fellows that year.

Slaymaker, one of four Ricci fellows who participated in Friday’s event, spoke to the gathering via Skype from Chicago, where he’s currently working on genome-editing tools to treat autism spectrum disorder.

“I’ve never met you, John,” Slaymaker told Ricci, who retired in 2001. “But I consider you my scientific grandfather. I’ve carried your name around with me for 10 years now. … I can’t express enough how much having your name attached to mine has changed my life.”

Someday in the near future, Slaymaker said, he hopes to pass the torch to the next generation of scientists, just as it’s been passed from Ricci to Stevens to him.

“Maybe I’ll create my own fellowship,” Slaymaker mused. “Ricci 2.0.”

Through it all, Ricci, now 77, sat with his cane, his face a mix of pride and barely contained emotion.

His office is long gone, swallowed up by renovations to the Science Building in recent years.

But his name will live on. Stevens announced Friday that, in addition to the ongoing fellowships, he and his family will underwrite a complete overhaul of the Science Building’s cavernous Room 120.

Upon completion, it will be christened the John Ricci Lecture Hall.

“I’m very surprised,” Ricci said quietly after the announcement. “It’s difficult to describe.”

What else can the professor say?

The kid with the F did good.

Bill Nemitz can be contacted at:

bnemitz@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.