“Second Sight: The Paradox of Vision in Contemporary Art,” now on view at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, is a rigorously bold exhibition that seeks to both disrupt and expand the language and (politicized) assumptions of the experience of a visual art exhibition.

Described by the museum as a show that “explores the experiential, psychological and metaphorical implications of the nonvisual in American art from the 1960s to today,” it, in fact, goes far beyond its thumbnail billing. Note my initial phrasing of “now on view,” despite the fact the exhibition includes work created by people who are blind and is led off by a purely auditory (aural) work by Steve Reich from 1966 that runs a phrase uttered by Daniel Hamm, one of the “Harlem Six” teens ultimately acquitted of the homicide associated with the Little Fruit Stand Riot of 1964.

Reich’s piece plays the fragment “come out to show them” on two channels (matching our two ears), at first in unison. But over 12 minutes, the channels slip out of sync (and multiply) to the point where the words are buried under the interference effects of the mismatched tracks and are no longer intelligible. The stated phrase (Hamm was requesting medical treatment after being beaten by police) breaks down over what seems to be a very long time, but in the context of the years during which the innocent were incarcerated (all but one were acquitted) and beaten by members of the justice system, the minutes pale in comparison.

This is a worthy introduction to “Second Sight.” It underlines the (essentially incomparable) experiential difference between the subjects of the work and the art audience. It also introduces the unexpectedly intense political footing of the show.

Curator Ellen Tani has been the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at the museum. (Unfortunately for us, she’s now in the process of moving on to the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.) Her catalog essay “The Vocabulary Won’t Hold It” lays out the fundamental problem of the current discourse (the terms we use to discuss a subject – the very ground of culture) about not only visual art but thinking in general.

Ann Hamilton, “face to face • 2,” from the series of 67 pinhole photographs, “face to face,” 2001, pigment print. Image courtesy of Ann Hamilton Studio.

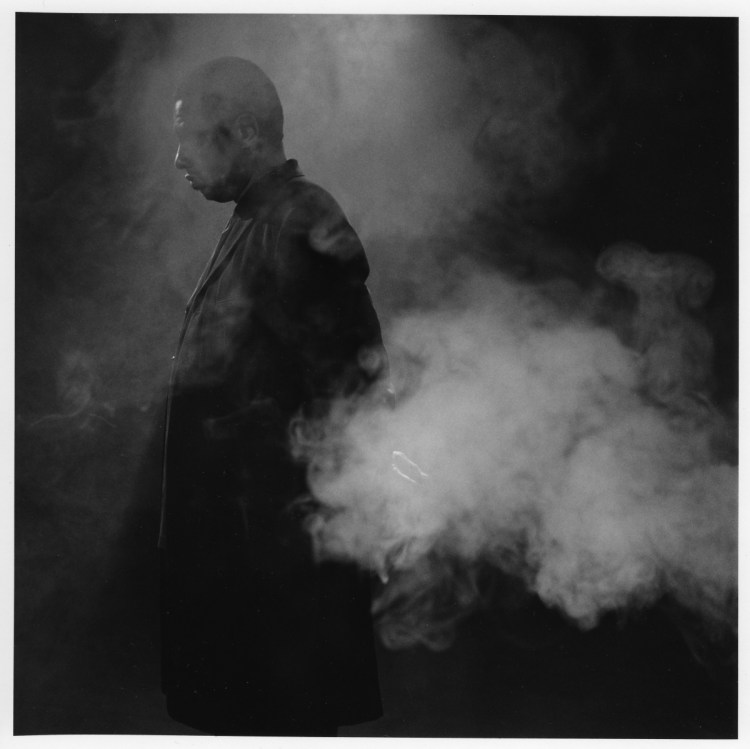

The work in this show is exciting, sometimes witty and often poignant. It leans towards the metaphorical but with a heavy reliance on perception. This matching of the perceptual with conceptual makes “Second Sight” unusually engaging. The first room (after the Reich piece in the entry) is led by Nyeema Morgan’s “Like It Is: Those Extraordinary Twins,” a brilliant drawing that purports to eclipse part the cover of a book of Mark Twain stories; a suite of Ann Hamilton’s pinhole photographs taken by using her mouth as the camera (she opened her mouth to expose the film, capturing a picture of another’s face through an aperture that looks uncannily like an eye); and Terry Adkins’s “Off Minor (from Black Beethoven),” a monstrously scaled and terrifyingly loud industrial music box cylinder. (We see Adkins appear and disappear in a cloud of white smoke – he is black – later in the show as the musician whistling an old Negro spiritual in Lorna Simpson’s excellent video “Cloudscape.”)

Moving on, a particularly notable work is Carmen Papalia’s installation “When We Make Things Openly Accessible We Create a Force Field.” Papalia, who is blind and who will be leading a walking tour at Bowdoin as part of “Second Sight,” offers banners and statements, but also a small, physical sanctuary complete with a shag carpet, pillows (which visitors can handle and use), chairs and a Robert Venturi couch (not my favorite architect, but he designed a super comfy couch).

Sophie Calle, “Blind #14,” as installed in the 2012 exhibition “Spies in the House of Art: Photography, Film, and Video,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, New York.

What particularly struck me about Papalia’s installation was the poignancy of his phrases printed on banners, pillows and the stacks of prints that reminded me instantly of Felix Gonzalez-Torres who is known for such shareable piles (and just to the left of “Openly Accessible” is the first of Gonzalez-Torres’s several bead hangings in the gallery doorways, a series of tactile works about vision loss). I was taken by Papilia’s text (so I took one) that included “OPEN ACCESS … ACKNOWLEDGES THAT EVERYONE CARRIES A BODY OF LOCAL KNOWLEDGE AND IS AN EXPERT IN THEIR OWN RIGHT.” For me, this phrase fundamentally captures the spirit of American art, since I believe our culture has never swayed from this type of thinking, the very essence of Romanticism’s valorizing personal perspective over the objective scientific truth of Enlightenment thinking.

This may be the real source of “Second Sight’s” true power: It forces the visitor to think in terms of varying perspectives. While I commend the identity politics orientation of the Portland Museum of Art’s 2018 Biennial, it doesn’t spark discussion, empathy or controversy like “Second Sight.” Ironically, one of the words flying about in the aftermath of the Biennial is the term “tone-deaf,” which, in the context of “Second Sight,” comes across as inconsiderately oxymoronic.

“Second Sight” features plenty of exciting highlights. Shaun Leonardo’s “Sonny Liston” drawings stand out as masterful: Two drawings of the same famous photograph from the 1965 Liston-Ali fight in Lewiston feature shifted perspectives in which the black athletes come into view or fade out to reveal the white journalists and onlookers. Glenn Ligon’s “Come Out #6” reprises Reich’s & Hamm’s “come out to show them” phrase, but printed so many times that it is not legible except, ironically, where the inking is so complete that the background is pure black.

Robert Morris’s famous “Blind Time” drawings, made either by Morris while blindfolded or by a blind person to whom he gave directions, still stand out as surprisingly fresh. William Anastasi might be the broadest presence in the show with his drawings, but his “sound object” radiator is great: An unplugged old radiator against the wall with a speaker behind it subtly producing those familiar knocking sounds.

A truly exciting and unusual aspect of “Second Sight” is the dialogue, debate and even conflict among the works. Sophie Calle’s three examples from her 1986 series, “The Blind,” are photographic works stemming from Calle asking people who were born blind what they think of as “beauty.” One woman describes the breasts and buttocks of a Rodin sculpture. A child lists their mother and sheep. A man dismisses the question. This exhibition haunted deaf artist Joseph Grigely who saw it many times and penned unsent postcards to Calle working through his response.

Shaun Leonardo, “Champ (Sonny Liston),” 2015, charcoal. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

The linguistically sophisticated Grigely, whose two speech fragment works are among the most compelling in the show, struggles to find his thoughts and opinions about Calle’s work. He comes to detest it, seeing in it not the voice of the subjects but only Calle herself. Grigely’s final conclusion is withering: “Perhaps, Sophie, you might some day return what you have taken, might some day undress your psyche in a room frequented by the blind, and let them run their fingers over your body as you have run your eyes over theirs.”

Curator Tani has given us a rare powerhouse of an exhibition. “Second Sight” is challenging, provocative and politically poignant, but with no room for anyone’s privilege, elitism or self-righteousness. And yet through the quality of the art, the wit and the focus on perception and experience, it is also a thoroughly engaging exhibition for anyone.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.