Parivash Rohani stirred the chopped onions and bite-sized pieces of chicken sizzling in a large pot on the stovetop in her Portland kitchen. She was making fesenjan, a traditional Iranian stew with chicken, ground walnuts and pomegranate syrup, that is often served at the Persian New Year.

While she let the chicken and onions cook, Rohani pulled out a big jar of pomegranate syrup – so dark red it is almost brown – that her father brought to her from Iran. It was made by family friends who grow pomegranates in Ardestan, the city where Rohani was born. Rohani said it’s just pomegranate juice that’s been boiled – nothing is added, as might be in commercial syrups.

“Sometimes pomegranate is sour and we add a little bit of sugar, but this is good,” she said, tapping her stirring spoon on the side of the pot.

As many as 300 million people worldwide celebrate the Persian New Year, with dancing, food and other activities. Nowruz – which translates to “New Day” – begins on or around the spring equinox, which this year falls on March 21 in Iran, where the holiday originated centuries ago. The festivities last for 13 days, and typically include foods such as fesenjan and two other dishes Rohani made to go with it – an herb-and-egg dish called kookoo sabzi and Persian saffron rice, cooked until it develops a coveted crispy bottom layer, which is called the tahdig.

Nasser Rohani, Parivash’s husband, still remembers fighting with his siblings over the crispy bits when he was a child.

The Rohanis have not lived in Iran since the 1970s, but they still celebrate Nowruz (the Baha’i spell it Naw-Rúz) as a religious holiday that is an important part of their Baha’i faith. Rohani has been fasting since March 2 as part of her observance, and can’t eat until after sundown each day. “Many people think that Nowruz is important to us because we are from Iran,” she said. “But Baha’i is all over the globe.”

The National Iranian American Council estimates 228 Iranian-Americans live in Maine. Of those, Nasser Rohani estimates just 50 are Baha’is.

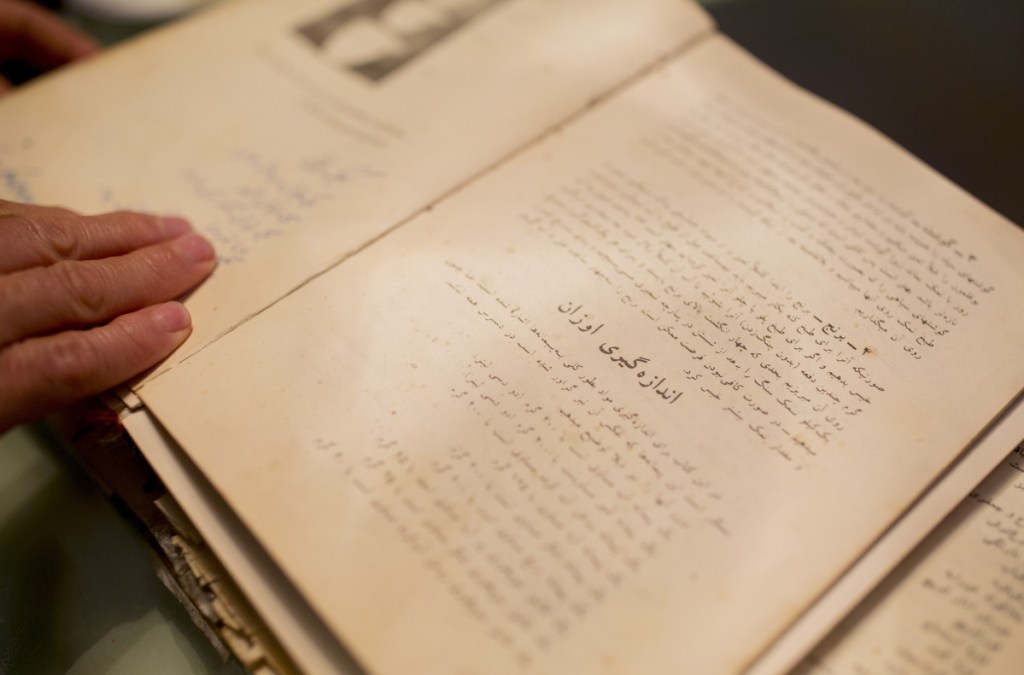

Rohani maintains a link with her native country through family and treasured possessions, such as a huge Persian cookbook, its binding falling apart, that her mother gave her when she married. She pulled it down from a shelf and thumbed through it. A few spots revealed handwritten notations she made years ago. She hasn’t used the book a lot, but certain recipes, such as an Iranian cake her daughter loves, became family favorites.

As she prepared the kookoo sabzi, she noted that “many, many people would have (this)” at the New Year. This afternoon, she decided to experiment with it – baking it in the oven in a muffin tin to make individual portions instead of cooking it on the stovetop as usual. Nasser, who loves to cook, rigorously stirred the herb-and-egg mixture.

“Mixing it so much will make it more fluffy,” he said.

The recipe serves eight, but Rohani says she loves it so much it only serves five in her household.

NEW YEAR, ANCIENT TRADITIONS

In Iran, preparations for the new year typically begin a month ahead.

“People do a lot of deep, deep cleaning – spring cleaning, really,” Rohani said. “And then you buy a lot of different sweets, or you bake a lot of different sweets. In some families, people come together and bake for days – rice cookies or chickpea cookies or pastry.”

Parivash Rohani has her husband, Nasser Rohani, taste-test rice while cooking a Nowruz meal.

Just as Christians buy a new Easter outfit every year, she said, Iranians splurge on new clothes to wear during Nowruz.

“When we were growing up we couldn’t wait for Nowruz because everything – your dress, your shoes, your socks – everything was brand new,” Rohani said. “You buy it in some families a month ahead, and then you go and look in the closet and say, ‘When is the new year coming? I want to wear my new dress.’ ”

On the Wednesday before the old year ends, people build fires and jump over them while singing a song, asking the fire to burn up their problems and give warmth and color to their lives.

Rohani left the fesenjan to bubble on the stove while she and her husband sat at her kitchen table to talk about the holiday. She cut up a honeydew melon for her guests but didn’t eat it herself since she was still fasting.

Although she has a recipe, she put the stew together without measuring anything, and she skipped the fenugreek and garlic chives listed as optional in her recipe because she doesn’t like them. While most Iranians cook with butter, Rohani prefers healthier olive oil.

A centerpiece of Nowruz is the Haft-Seen table, the couple explained. Families set a table with seven items that begin with the letter S. The items represent things that people hope to bring into the new year, such as garlic (seer) for health, dried fruit (senjed) for love, and vinegar (serkeh) for wisdom and patience.

Why the letter S? “There is not any rhyme or reason because it is more than 3,000 years old,” Rohani said.

Families also grow sprouts from lentils or some other plant for the table. The new growth must be a few inches long before Nowruz arrives.

“Iran is not a very green country,” Nasser Rohani said, “so to represent the coming of the new year, they have to show some green,”

Goldfish and money may also go on the table, along with a holy book for Muslims or Zoroastrians, or the Bible for Christians. People who are not religious often add a book of poetry.

The Haft-Seen table remains set for at least 10 days because after the equinox, families visit each other. The elderly give money – crisp, new bills – to the children who visit them. On the 13th day – the last day of the celebration – families go on a picnic.

“They have to picnic near a river – the flowing water – because it is a good omen to get the sprout thing and throw it in the water and make a wish,” Rohani said.

LOST AND FOUND

Persian New Year festivities are as lively as ever in Iran, Rohani said, because people view them as “an uprising against the government.”

“When the Islamic government took over, they wanted to get rid of all the traditional, important days because they didn’t want anything un-Islamic to exist and people enjoy it,” she said. But trying to ban holidays only made them more popular, and Persian New Year celebrations, especially, have blossomed.

Rohani was just 18 when the Iranian revolution broke out in 1979. She had planned to study law, but after the revolution Baha’is were not allowed to enter university, and if they were already enrolled, they were expelled.

Then her family’s home in Shiraz was burned down, and they lost everything overnight. Rohani and her two female cousins, ages 19 and 21, were sent to safety in India.

“After something so drastic, you don’t feel safe anymore,” Rohani said. “You feel like ‘my god, these are my people and none of them really stood beside me to defend me. How can I live here now?’ ”

After the revolution, 10 of Rohani’s friends – all Baha’i – were hanged.

Rohani stayed in India until 1986. There she met and married Nasser, who had come to India for an education, and the couple emigrated to California. They ultimately settled in Maine to be closer to her in-laws, who lived in New Brunswick at the time.

Rohani wasn’t taught to cook as a child. “When I was a girl, I was spoiled,” she said, but in India she and her cousins shared kitchen duties. Whoever got home from school first would start making dinner, “so we just learned by putting things together.”

Rohani eventually became a nurse, and a mom. She and Nasser have four adult children. Nasser recently retired after more than 30 years as a computer analyst at L.L. Bean.

It’s still not safe for Baha’is in Iran, Rohani said. A few months ago, her sister-in-law was arrested for holding a small religious meeting in her home. “She was in solitary confinement for a month,” Rohani said. “She was released on bail awaiting her sentence, and we are all really worried for her because she has a 9-year-old and a 12-year-old.”

HERE AND NOW

When all of the dishes, including a salad Nasser made, were spread out on the family’s kitchen island for serving, it made for a colorful display – the dark red pomegranate, the green herbs, the yellow saffron in the rice. The herbs gave the kookoo sabzi an earthy flavor, while the fesenjen was both sweet and sour. And it was easy to see why children fight over the fun-to-eat crunchy bits of rice.

Parivash and Nasser Rohani cook food for a Nowruz meal.

After dinner, Rohani served tea in beautiful gold and glass teacups from Iran. A silver spoonholder shaped like a swan held small, ornate silver teaspoons.

Although the Rohanis still feast on traditional Persian New Year dishes, they no longer celebrate Persian New Year as a cultural holiday, partly because many of the traditional festivities seem outdated to them. Rohani cleans her house every day, she says, and she has plenty of clothes. She doesn’t set out a Haft-Seen table. When she was a child, her father was in the army and her family moved so often, and so unexpectedly, that her mother stopped doing it.

“It’s beautiful, and I admire people who are committed to do it,” she said, “but my mother was never committed, so I never grew up having that every year.”

But Rohani will continue fasting through March 25. And on Nowruz, she and her family will venture out to do some kind of service – visit the sick in the hospital or perhaps residents of a nursing home, collect money for the poor – to give back to the community.

“We both left Iran a long, long time ago and we are here,” Nasser Rohani said. “We are Americans now.”

Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.