Once there was a tree …

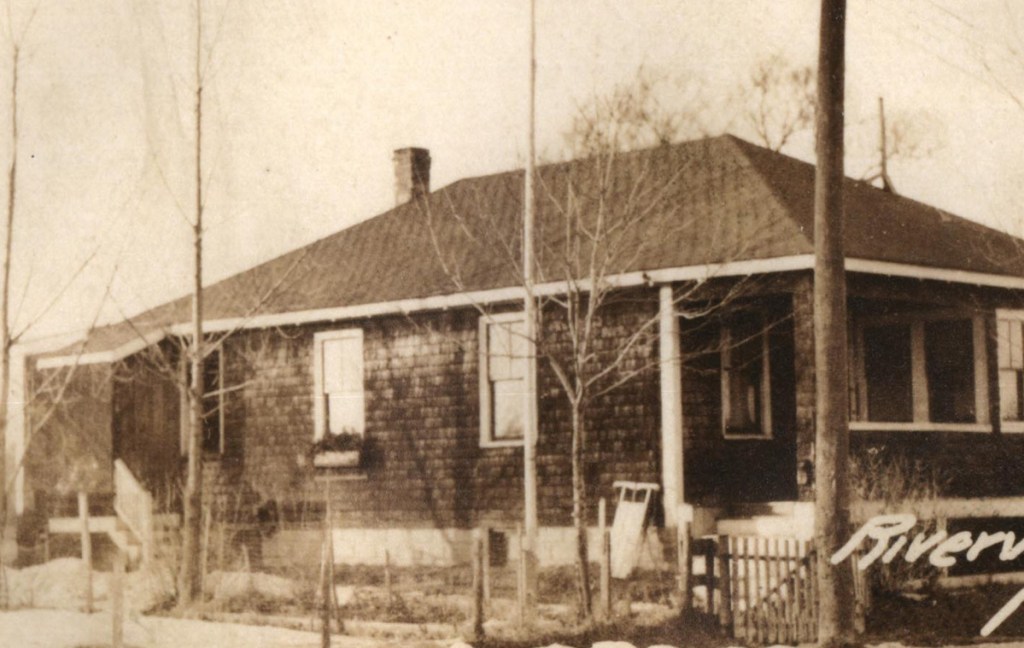

A red maple tree. It was a sizable tree, though not immense. It stood next to a small, shingled brown bungalow on a one-block, dead-end street in Portland, Maine. The tree sheltered the little house, and the woman who lived there, too. In spring, she remarked on its beautiful crimson buds. In summer, she enjoyed its leafy green shade, which kept her house cool and comfortable. Every fall, the woman spent many hours raking, but she never minded, even when she got blisters on her fingers, because the red maple had the most beautiful red leaves imaginable. In winter, its handsome, battered trunk – bark peeling and specked in lichen – greeted her like an old friend as she stepped off the front porch each morning to go to work. “Good morning,” she’d nod at the tree, and it seemed to her the wise old tree wished her good morning, too.

That woman is me. And this fall, I faced a decision that tore me apart. Did the red maple tree need to come down?

BEFORE

My house was built in 1915. A tax photograph taken of the house and yard just nine years later shows the red maple, a spindly thing. Portland city arborist Jeff Tarling’s best guess is that the family who lived here then – possibly Frank H. Sawyer, clerk at a grain company, according the 1916 City Directory, or perhaps Jens Christian Bruns and his wife Alberta, who owned the place by 1924 – yearned for some pleasant shade in what was then a new development of modest matching bungalows. ” ‘I’m sitting on the porch in bright sun,’ ” he pictured them thinking. ” ‘I’m going to get a tree here.’ ” Tarling turned to me, smiling. “They thought of you when they put this tree in.”

It was a “little teeny tree,” he said.

But it must have liked its new home, because over the years it grew big and strong. By the time the red maple and I got acquainted just a few years ago, its trunk was the girth of an imposing column, and the tree itself towered over me and the single-story house it was planted to shade. A sizable branch bent toward the house, seeming to snuggle. (That’s not how the house inspector saw it. He warned me about a squirrel highway.) Several more fair-sized branches reached up to make a three-dimensional V shape of sorts that supported the crown. The maple’s position near the house – too near, Tarling said – made it feel private and secure.

Squirrels chased and chattered up the tree and back down again. Birds perched on its accommodating branches. The cat in residence, Trixie by name, made occasional and frenetic runs up the trunk, while the neighbor’s little boy was partial to the peeling bark. Though the roots defied me at every turn when I tried to carve out garden beds, it felt like a friendly game we played.

The red maple contained its own world, too. “There’s a microscopic ecosystem within a blade of grass,” Jan Santerre, project canopy director for the state’s Urban Forestry Program, said when I asked her how the tree shaped my backyard environment. “Certainly there is an ecosystem within a tree and all the fungi and the bugs and the animals that depend on it.”

The center of the tree, it’s true, had a gap, a gash really, where it looked as though a scaffold branch should be – had been. And the maple dropped small – and sometimes not-quite-so-small – branches on the lawn more often than perhaps was strictly usual. But it leafed out beautifully each spring, and I doubt I’d have given its health a second thought until I heard different from a parade of experts.

First came Press Herald Maine Gardener columnist Tom Atwell, who strolled around the yard a few years ago to help me envision a garden. He took one hard, practiced look at the red maple, described it as dying, and told me I’d need to take it down.

I did not.

Some months went by. Lisa Fernandes of Portland’s Resilience Hub, came over for a permaculture consult. She circled the maple, appraising it with a critical eye and told me to remove it. I must have looked stricken because she added gently, “It can be heartbreaking to take a tree down.”

I waited.

Sixteen months passed.

Winter approached. My third winter in my home. During wind and ice storms I found myself avoiding the corner of the house where I feared the tree could hit if it fell.

Reluctantly, I asked around for the names of arborists, preferably one who will err on the side of inaction, I specified. Arborists, I was learning, run the gamut. “It’s like going to a doctor,” Tarling told me. “Some think you’re fine. Others think you need your knee replaced.”

One early fall day I made an appointment, and a week or so later, Kevin Bachelor of For-Tay Landscaping in South Portland came round to take the tree’s measure. He, too, thought its days were numbered.

How long do I have? I asked.

“Three storms. Maybe two,” Bachelor said.

THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

Tarling didn’t make the decision any easier when he stopped by in October and told me the tree had good “root flair,” that it had survived the summer’s drought surprisingly well and that its condition wasn’t “catastrophic.” But he wasn’t exactly sanguine, either, guessing my red maple had been damaged in a storm – he ticked off the ice storm of 1997, the Patriot’s Day storm, and hurricanes Bob and Gloria as possibilities.

Press Herald Source editor Peggy Grodinsky puts a hand on a red maple tree in her yard before it was cut down on Jan. 12.

The top blew out, Tarling said, and decay gradually set in. My nearest neighbors, longtime residents, didn’t remember the event. Tarling, who has been city arborist for going on 28 years and knows Portland’s trees with the intimacy of an old friend, thought he did.

The red maple could last a few more years, he said. Trees often surprise him. On the other hand, “I wouldn’t go out in a thunderstorm and stand under the tree, or in a big, heavy snow.” When you’re deciding the fate of a tree, there are two factors to consider, he advised: first, its health, and second, what he called “the target.” As he put it, “If the tree fails, what’s underneath the tree?”

In the case of my red maple, the answer was, in part, the power lines.

“My thought is that” – Tarling pointed at a high branch – “could fail, and it’s going to take out this primary wire, and knock out the neighbor’s power line. And it’s going to be that coooold day in February.” He stretched out the word and laughed. “And because you’re on a dead-end street, you’re not going to be a high priority for repair. It probably won’t knock your power out, but it could take out the rest of the street and then they’d say, ‘Our power was great until Peggy’s tree damaged it.'”

I’m a newcomer to the neighborhood. I have lived in my house not yet three years, while the red maple has called the place home for a century. Neighbors aside, what gave me the right to kill it? When my sisters and I were small, we gave my mother, an accomplished gardener, an apple tree one Mother’s Day. It thrived for some five years until one day she decided it didn’t suit the lines of her garden. And just like that it was gone.

Like my mother, Press Herald garden columnist Atwell had no romantic notions about my tree. “The tree is a living thing, but there is no problem with taking it down,” he said when I called him, indecisive and distressed. Just plant another maple in its place, he suggested.

“I love this tree. How can I take it down?” I pressed. “I don’t even feel comfortable weeding.”

An incredulous silence blared from the other end of the phone.

“You got to pull the weeds!” Atwell finally said. “Plants have a lifespan. Sometimes it’s over.”

DEATH WARRANT

I live in the Forest City and in the Pine Tree State. I live a mere 20-minute drive from the late Herbie, a massive 217-year-old American Elm that stood in Yarmouth, so beloved it got its own name, its own caretaker (town tree warden Frank Knight) and its own Wikipedia entry. Tarling told me that in 1854, Captain George H. Preble counted every tree in Portland. ” … no person builds a house on a respectable street but his first object is to plant trees about it,” Preble wrote at the time. Tarling added that when the city was given Deering Oaks Park in 1879, the Deering family put a condition on the gift: “Spare the woodsman’s axe.”

A number of maples grow on my own street, all roughly the size of my red maple. Maybe each of the families that lived in each of the then-new bungalows a century ago also longed for shade. The trees grew up together, not unlike the children on the block who grew up together over the years. Were they fretting about their ailing old friend? Would they mourn its demise?

Don’t ask me why at this juncture I thought it was a good idea to read German forester Peter Wohlleben’s fascinating “The Hidden Life of Trees.” “When you know that trees experience pain and have memories,” he wrote in the introduction, “and that tree parents live together with their children, then you can no longer just chop them down and disrupt their lives with large machines.”

It confirmed my worst fears. Can trees feel? I anxiously asked Santerre, of Maine’s Urban Forestry Program, after reading that. “My biology background and my scientific background would say no,” she answered, then paused. “But I’m also not a tree.”

On Oct. 29, a wind and rain storm ripped through Maine, toppling hundreds of trees. Among them was a tall, thin, erect white pine that stood directly across the street, a favorite hangout for passing crows and hawks. It took its last breath – yes, trees breathe – early in the morning. By the time I woke up, it lay on the ground, its crown stretching toward the street, its trunk precisely aligned alongside the length of my neighbor’s house, missing it – missing her – by a barely a foot.

I had prayed the red maple would fall, on its own terms, in its own time – missing the house, the street and the power lines.

In fact, my red maple survived without so much as a scratch – making it even more wildly unfair that that storm and the damage it wrought sealed its death warrant.

City arborist Jeff Tarling talks to Grodinsky about the health of a century-old red maple tree on her property.

THE WOODSMAN’S AX

For weeks, the song that Lancelot sings to Guinevere in the musical “Camelot” ran on a loop inside my head, “If ever I would leave you, it wouldn’t be in summer. Seeing you in summer, I never would go.” The ardent knight sings his way through the rest of the seasons, and likes those options no better. “Oh, no! Not in springtime! Summer, winter or fall! Never could I leave you at all.”

If you ask me, there is no good time to cut down a tree. Certainly not one that looks, at least to the inexpert eye, like it has years of life left. But if you ask the experts, late fall or winter is the right time. The birds have flown, so you won’t be an avian homewrecker. Unless you’re sheltering a hibernating bear – the red maple wasn’t – you are probably OK on that count, too. You’ve had one last season to delight in the tree’s flaming red leaves, and once they fall, their lack makes the arborist’s job easier, while the hard, frozen ground protects the yard from any heavy machinery that’s required to do the job.

“I’m not sure there is ever an easy time to let things go,” a sympathetic Tarling said.

With a heavy heart, I scheduled the day of execution.

On Jan. 11, a cold, beautiful, star-lit evening, I came home from work, stepped into snow up to my knees, wrapped my arms around the tree’s trunk – they didn’t meet, or come close to meeting – and sobbed.

Jan. 12 dawned gray and gloomy, “a good day for grief,” my friend Charmaine Daniels said.

At 8:10 a.m., my smartphone pinged me with my day’s schedule: Tree comes down 🙁

By 9 a.m., Bachelor was setting up, and Richmond woodworker Jeff Raymond, who hoped to turn the wood into a few of his beautiful, handcrafted bowls, had arrived.

“If you have the opportunity to get any of the wood, do something with it,” Santerre, who owns a necklace and artwork made from Herbie, had suggested. “It sort of memorializes it and eases the sting.”

By 10:19 a.m., Bachelor had put his equipment in place, and he clambered up the tree in spiked boots. I retreated to the back of my house, unable to watch. The sounds of the chainsaw followed me like a scream.

By 2:11 p.m., there was no red maple. It took 100 years to grow and four hours to demolish.

AFTER

A week earlier, I’d spoken with Tim Vail, an Orrs Island arborist with a reputation for saving trees. “It’s never easy,” he said. “And it’s not going to get much easier when it’s gone. You’re going to have a stump there until you plant a tree.”

He was right. I still feel a little stab of shock every time I come home. My bungalow looks forlorn, and Shel Silverstein’s “The Giving Tree” rattles around in my head: “I wish that I could give you something … but I have nothing left. I am just an old stump.”

On the Seven Stages of Grief scale, I remain somewhere between 2 (pain and guilt) and 4 (depression, reflection, loneliness). Possibly the worst moment of the day my red maple came down was when Bachelor told me he was surprised to find that no bugs had infested it. Had I made a mistake? – a question I asked him at least seven times the morning he was setting up. If he was exasperated, he kept it to himself. And if I made a mistake, it was irrevocable.

Stage 7 (acceptance and hope) still eludes me. “One thing that will give you some hope is that you can plant another tree,” Vail suggested. “If you plant another tree, you will know you have done something to compensate for the urbanization of the planet. You are going to plant another tree for someone who will be there in 100 years.”

It may be a quince tree, to shower the yard every spring with beautiful pink blossoms and my kitchen every fall with tempting quince tarts. Or, like the dog owner who buys the same breed time and again when his pet dies, it may be a red maple.

Send questions/comments to the editors.