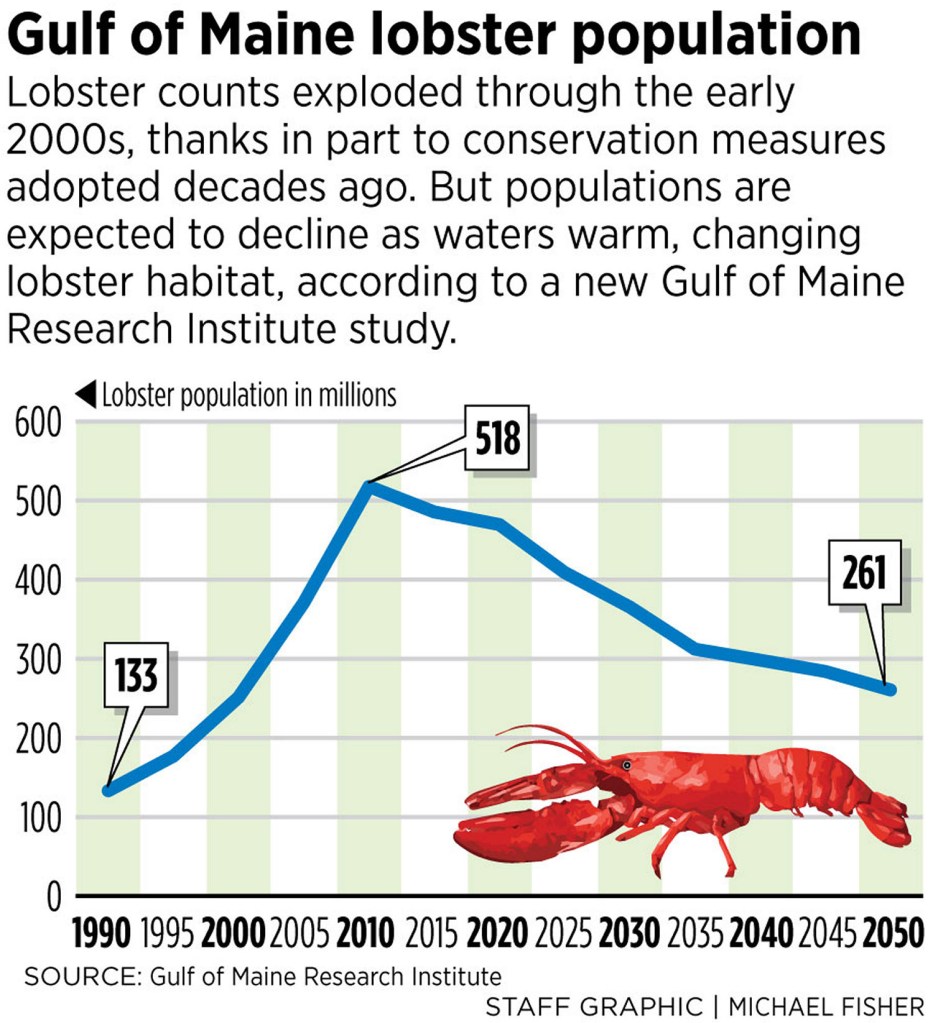

The Gulf of Maine lobster population will shrink 40 to 62 percent over the next 30 years because of rising ocean temperatures, according to a study published Monday.

As the water temperature rises – the northwest Atlantic ocean is warming at three times the global average rate – the number of lobster eggs that survive their first year of life will decrease, and the number of small-bodied lobster predators that eat those that remain will increase. Those effects will cause the lobster population to fall through 2050, according to a study by researchers at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, the University of Maine and the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration.

Looking ahead 30 years, the researchers predict a lobster population “rewind” to the harvests documented in the early 2000s. In 2002, 6,800 license holders landed 63 million pounds of lobster valued at $210.9 million. By comparison, 5,660 license holders harvested 131 million pounds valued at $533.1 million in 2016.

“In our model, the Gulf of Maine started to cross over the optimal water temperature for lobster sometime in 2010, and the lobster population peaked three or four years ago,” said Andrew Pershing, GMRI’s chief scientific officer and one of the authors of the study. “We’ve seen this huge increase in landings, a huge economic boom, but we are coming off of that peak now, returning to a more traditional fishery.”

Industry leaders have been girding themselves for a decline in landings ever since the recent boom began. While not everybody believes the decline will happen that fast or fall so much, most lobstermen admit the impact that warming water has had on their fishery, said Dave Cousens, the president of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association. It drove up landings by pushing lobsters into the Gulf of Maine, and over time it will drive lobsters out to colder offshore waters or the Canadian Maritimes, he said.

“We know that time is coming,” Cousens said. “That’s why the older generation is encouraging our kids to diversify their fishing, go into aquaculture or look to fish one of the warm-water species that’s coming up, like black sea bass. They’ve got to start thinking about it. I think the lobster fishery is still going to be here, but not like it is now. We’ve got to keep protecting what we can, but start thinking about what we’ll be doing when the boom is over.”

Curt Brown, a lobster biologist at Ready Seafood in Portland, said the industry needs to keep funding lobster monitoring efforts, especially in the first few months of the lobster’s life cycle, so it has that “canary in a coal mine” to help predict a decline on the horizon, but he is skeptical of the magnitude of the decline that is predicted by the study’s model. Instead he would rather focus on penetrating new markets, developing new value-added products and extending the shelf life of high-value products.

“I don’t worry too much about predictions 30 years out,” said Brown, who is also a licensed commercial lobsterman. “Historically, we don’t have the best track record of prediction over long-term scales. That being said, I do not think landings will increase indefinitely and we must be prepared as an industry for a world where we don’t rely on volume to drive the value of our fishery.”

As grim as the study’s lobster stock outlook may be for Maine’s most valuable fishery, the forecast could have been far worse if it were not for the industry’s commitment to conservation measures, like throwing back large lobsters and egg-bearing females. These measures protect the lobsters most likely to produce large amounts of eggs. For example, a 5-pound lobster can produce a thousand lobsters, while a 1½-pounder produces 100, Cousens said.

Without such conservation measures, the Gulf of Maine lobster population would shrink another 20 percent by 2050, Pershing said. By then, the water off the coast of Portland over the summer will probably feel like the summertime water off the coast of Rhode Island does now, he said. The last time the Gulf of Maine had a population and corresponding harvest numbers like that would have been in the 1990s, Pershing said.

“That is the difference between holding on to a reasonable fishery and a really challenging situation for the state’s most valuable fishery,” Pershing said. “If Maine did not v-notch (the practice of marking egg-bearing female lobsters with a notch in their tail to prevent future harvesting) or have a maximum size limit, the impact on our future fishery will be worse then the impact that shell disease had in southern New England. ”

CONSERVATION MEASURES

The conservation measures more than doubled the population boom in the Gulf of Maine that would have been expected from the warming temperatures alone, the researchers said. As more habitat in the Gulf of Maine approached the optimal 61.5 degree summer water temperature for lobster, and more lobster eggs survived their first year of life, the size of the local lobster population would have been expected to increase 242 percent over the last 30 years, the researchers said. Instead, with the conservation measures in place, the population grew by 515 percent.

Scientists don’t know exactly why the number of lobsters that survive the first year of life falls as the water temperature begins to exceed 62 degrees, Pershing said. The scenarios that scientists are exploring to explain the increase in mortality in warmer waters range from a decline in food available to lobster larvae to a direct impact on a baby lobster’s physiology to the increase in predators able to remain active in warmer waters for more of the year.

Although they don’t know the why, researchers found a clear link between lobster abundance and water temperatures across New England over the last 30 years.

The research team used advanced computer models to simulate the ecosystem under varying conditions, allowing them to understand the relative impacts of rising water temperatures, conservation efforts and other variables. Their results show temperature change was the primary contributor to population changes, but local conservation methods helped the Gulf of Maine fishery take advantage of changing waters over the last 30 years, the study concluded.

Previous generations of Maine lobstermen that established conservation methods – local fishermen began v-notching in 1917 and set a maximum size limit in the 1930s – have given today’s lobstermen a gift, Pershing said. It is a gift that Maine lobstermen like Cousens tried to share with other lobstering states, traveling throughout Canada and as far south as New York to convince skeptical audiences to mark and spare their breeders from the trap.

In southern New England, where the lobster fishery has shrunk to 78 percent of its size 30 years ago, harvesters did not impose a maximum size limit until 2008, and the practice of v-notching is voluntary and less common. The study concluded the southern New England lobster population would have decreased by 57 percent instead of the catastrophic 78 percent if it had implemented Maine’s conservation methods.

“I know this forecast may cause a certain amount of stress, but it is only bringing us back to conditions more typical of the fishery in Maine,” Pershing said. “We were incredibly lucky to have lived through this fishery boom, to have been in a position because of the conservation measures in place to make the most out of it, but now we are going back to a more normal state of the fishery. But even under our warmest temperature model, there will still be a fishery.”

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and will be published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Penelope Overton can be contacted at 791-6463 or at:

poverton@pressherald.com

Twitter: PLOvertonPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.