Mainers are learning more than they ever wanted to know about opioid addiction. We’ve learned that it can start with a routine prescription for pain medicine, or a moment of bad judgment at a party.

We’ve learned that people with unrecognized depression, anxiety or other mental illnesses are especially vulnerable to dependence on a drug that manipulates the pleasure and reward center of their brains.

We’ve seen that once it’s established, addiction is a hard cycle to break, and in most cases it takes more than willpower to get well, with multiple relapses being the norm.

And we’ve learned that it’s deadly. As recounted in the 10-day Portland Press Herald series “Lost: Heroin’s killer grip on Maine’s people,” opioid abuse has been killing, on average, a Mainer every day, and no corner of our state has been spared.

That’s what we’ve learned. But what has Gov. LePage learned?

He is still fighting the same battles he began years ago, opposing treatment initiatives while the public health crisis exploded on his watch.

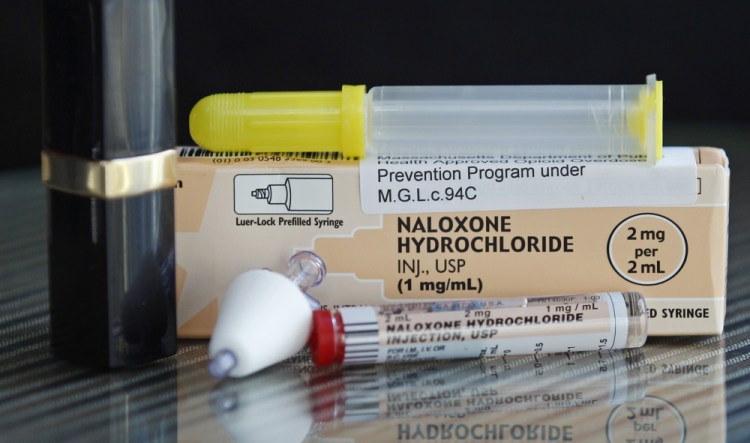

In 2013, when Maine was reeling from 176 overdose deaths, LePage vetoed a bill that would put the overdose antidote drug naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan, in the hands of police, firefighters, at-risk drug users and their families. He relented somewhat the next year but continued to push back, vetoing another bill to allow naloxone to be distributed without a prescription at pharmacies, claiming that “it serves only to perpetuate the cycle of addiction.” By the end of 2016, the annual death toll had climbed to 376 in Maine, a pace the state maintained through the first half of 2017.

The latest naloxone bill was passed over his objection, and was sent to the state Pharmacy Board for rulemaking. The board’s work was done in August, but the regulations have stalled in the governor’s office.

LePage has not said why he is standing in the way of giving life-saving medicine to people who would otherwise die, but his series of veto messages indicates that he holds to a discredited belief that people with opioid use disorders have the power to stop taking drugs at any time they want.

But that’s not what the experts say. For years, consensus in the medical community has been that addiction is a “primary” disease of the brain and body – one that occurs spontaneously and not as a result of an injury or another disease. According to the American Society of Addiction Medicine, “Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response.”

Most people with addictions reach a point where they want to quit, but can’t. One of the most dangerous times for opioid addicts is when they relapse after abstaining for a period and don’t have the ability to tolerate what used to be a normal dose.

A dose of naloxone in the hands of a friend or family member won’t cure an addiction, but it saves lives, and people who have been revived go on to succeed in the hard work of recovery.

Having it on hand is no more an excuse for an addict to keep using than having a fire extinguisher around would be an excuse to play with matches.

Mainers have had to learn the hard way about this crisis.

By now, Gov. LePage ought to know what to do, too.

Send questions/comments to the editors.