SOUTH PORTLAND — Maine Department of Corrections Commissioner Joseph Fitzpatrick said Thursday he doesn’t believe Long Creek Youth Development Center should close, as some have suggested, but he agreed with the major points raised in a recent independent audit of Maine’s only youth detention center.

Fitzpatrick said the audit, released last week, validated much of what administrators already had identified as challenges at the facility. He also said a number of improvements, including installing a new superintendent and filling numerous vacant positions, have been made and more are on the way.

One initiative is the development of an unspecified number of regional secure psychiatric facilities specifically for youths with significant mental health needs. That is being coordinated with the Department of Health and Human Services.

“One of the critical things to recognize and realize is, the audit wasn’t forced on us in any way,” he said. “We actually welcomed it. And the reason we welcomed it is … the more voices we have at the table, the more objective looks at our system, that’s how we get better.”

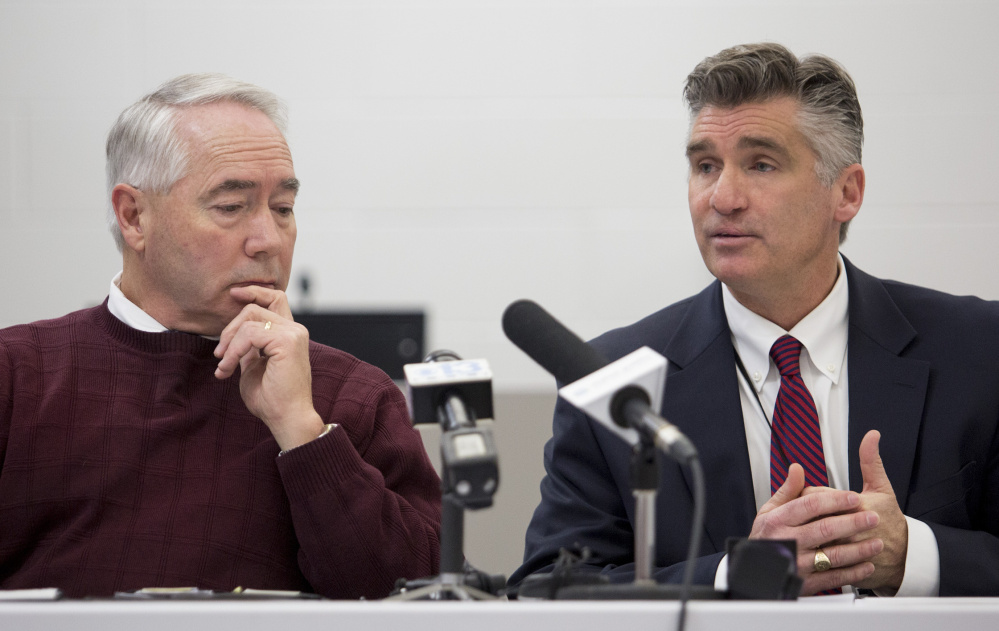

Speaking to reporters for more than an hour and a half, Fitzpatrick, along with his associate commissioner of juvenile services, Colin O’Neill, answered a host of questions about the audit conducted in September by the Center for Children’s Law and Policy, a national organization focusing on youth justice.

The commissioner said he plans to sit down soon with a number of advocacy groups as well, including the American Civil Liberties Union of Maine, which made the case last week that the state should close Long Creek. Fitzpatrick said Thursday that he didn’t respond to the report when it was released last week because he was dealing with a death in the family.

‘KIDS DON’T BELONG IN PRISON’

Alison Beyea, the ACLU’s executive director, said she’s happy to meet with Fitzpatrick and was pleased that he’s taking steps to improve the facility, but that doesn’t change her opinion.

“The system is fundamentally flawed,” she said in an interview Thursday. “No matter how hard he tries, he can’t fix that. Kids don’t belong in prison.”

The audit report was commissioned by the state’s Juvenile Justice Advisory Group, partly in response to the suicide of a 16-year-old transgender boy, Charles Maisie Knowles, whose death in November 2016 prompted renewed scrutiny of how the 160-bed correctional facility in South Portland treats LGBTQ youths and young people with serious mental health problems.

Knowles’ death also resulted in the facility’s then-superintendent, Jeffrey D. Merrill II, being placed on leave. He resigned a short time later.

“Their goal was to improve practices here and we welcome that level of scrutiny,” Fitzpatrick said of the advisory group’s review.

Six investigators visited the facility in early September and observed both staff and residents.

Although the auditors praised staff as hard-working and professional, they also concluded that most were overworked and burned out. Also, many had not been trained to handle some of the major mental health issues that some residents present.

Those circumstances led to dangerous, unsafe conditions and have limited the center’s ability to fulfill its mission of rehabilitating youths and reintegrating them into society, the report found.

The facility is so short-staffed that workers often are forced to work double shifts. So far this year, the staff of roughly 170 has logged 5,454 hours of overtime. Because workers are selected for mandatory double shifts on a reverse seniority basis, the least experienced workers are often left working the longest hours.

NEW SUPERINTENDENT STARTED IN OCTOBER

The commissioner acknowledged that staffing levels at Long Creek have been a problem. Since July, though, 30 positions have been filled.

“We are fully staffed at this point,” Fitzpatrick said, noting that some new staff members hired are mental health acuity experts.

He also said leadership has greatly improved. Not long after the audit was conducted, Long Creek also hired a new superintendent, Caroline Raymond, formerly the CEO of Day One, a youth substance abuse services agency. She started in mid-October.

A new director of education has been hired recently as well, and the Corrections Department is in the process of finding a contractor to provide special education services at the facility. As many as 60 percent of the 68 residents currently at Long Creek qualify for special education services, O’Neill said.

Beyea said she believes corrections officials are trying to do the right thing.

“But this report is one of many reports issued over decades on how the youth center can’t provide services to youth,” she said.

Perhaps the biggest concern cited by the audit, and by Fitzpatrick on Thursday, was providing adequate mental health services to residents.

The commissioner acknowledged that in many cases, residents with severe mental health needs who end up at Long Creek don’t belong there. He said when O’Neill surveyed the population earlier this year, the results were startling.

“There were kids coming in the door with a level of mental health needs we had never seen before,” he said.

Knowles’ mother has said she begged staff and doctors to give her son the mental health treatment he needed before he took his life, but was rebuffed because Knowles was only detained at the facility temporarily. The population there falls into two broad categories: youths who are detained and those who are committed.

Like adults in county jail, detained youths are awaiting the final outcome of their legal case, with the length of their stay ranging from a few days to several weeks or months. Committed youths are more permanent residents whose legal cases have been fully resolved, and will sometimes spend years at the facility receiving treatment and counseling while attending school.

will lawmakers take legislative action?

Corrections officials have said everyone at the facility, regardless of whether they are housed temporarily or long term, has the same access to care.

But Fitzpatrick said the issue about mental health treatment has indeed been a growing problem and one he said he identified in advance of the audit. About five months ago, before the audit was conducted, he sat down with Gov. Paul LePage to talk of his concerns about these residents.

“You can’t fix (a problem) if you don’t have an option. The governor said, ‘Create an option.’ So that’s what’s happening,” Fitzpatrick said.

The solution is to explore creating regional residential facilities for youths, although Fitzpatrick said he could not provide additional details. He said DHHS was taking the lead on that effort. A representative of that department did not respond to a request for more information.

As recently as 15 years ago, Maine operated two 160-bed facilities – Long Creek and the former Mountain View Youth Correctional Facility in Charleston – often at capacity.

Mountain View has since been converted to an adult correctional facility.

Despite calls for its closure, Fitzpatrick reiterated that he thinks there will always be a need for a facility like Long Creek.

“We’ve seen a steady decline in our youth population,” he said. “I don’t see us closing the door to any facility, but I’ll listen to anyone and I’ll be open-minded.”

It’s not clear whether the audit will lead to any legislative discussion when lawmakers reconvene in January.

Last week, both Democratic and Republican lawmakers said the audit report confirmed that there remain problems at Long Creek, but also with the state’s broader system of mental health services.

“We need political will. I do think there is a growing energy in this state to find a new solution,” Beyea said. “Other states have used a wide variety of tactics to find ways to get kids out of prison, but the uniform basis for those decisions is the acknowledgment that kids should never be locked up.”

Eric Russell can be contacted at 791-6344 or at:

Twitter: PPHEricRussell

Send questions/comments to the editors.