LEWISTON — Pointing to the words on the page, Ja’Syiah Doyle reads out “I . . . am . . . a . . . CROC-odile!” then tips her head sideways and turns on her megawatt grin to kindergarten teacher Lynn Adams. “Beautiful! That’s right,” Adams tells her.

Across the table, Jaycob Costello takes his turn: “Ba . . . Ba . . . Big!” he reads, twisting his feet around the legs of his small chair as he concentrates. “Sssssmall!”

Adams’ class is a typical kindergarten class in Maine, where the lessons are focused on teaching students about colors, numbers, shapes and letters.

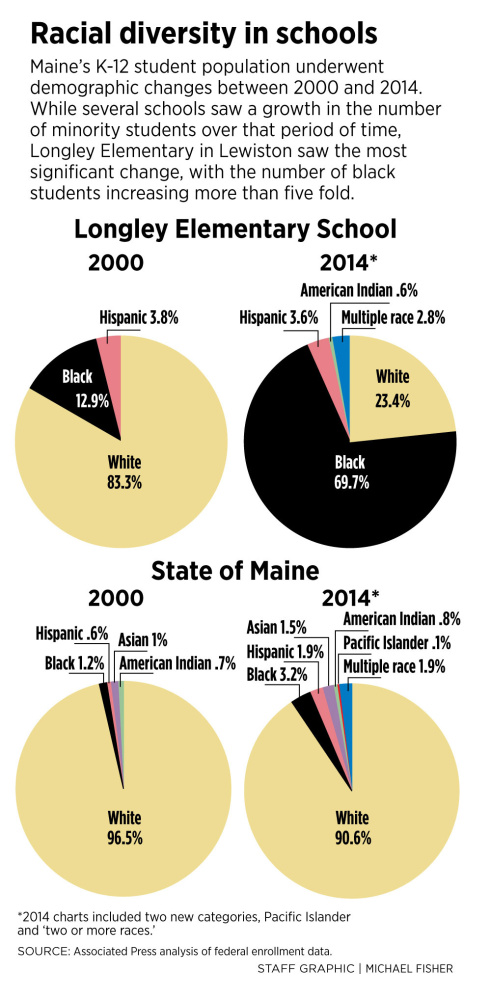

But a huge difference is the students themselves: In the whitest state in the nation, 75 percent of the students here at Longley Elementary School are minorities, mostly in families of immigrants who have arrived in Maine within the last 20 years. By contrast, 15 years ago, minorities made up just over 15 percent of the students at Longley.

Recent waves of immigrants coming to Maine have rapidly changed the racial makeup of schools, with huge impacts on state education funding and potentially altering Maine’s economic future.

As local districts quickly moved to provide new supports and services to immigrants, state funding for English Language Learners – or ELL students – has almost tripled in the last dozen years, according to the Maine Department of Education.

In 2006, the state allocated $7.9 million in ELL funds for 3,128 students. This year, the state allocated $19 million in ELL funds for 5,349 students.

Longley Elementary has seen the biggest change in racial makeup between 2000 and 2015, going from 83 percent white in 2000-2001 to 23 percent white in 2014-15, according to an Associated Press analysis of federal enrollment demographics data. In Maine, the data reflect how racial diversity that was initially clustered in bigger cities like Portland and Lewiston is moving into smaller towns and suburbs.

In 2000, only 18 Maine schools had fewer than 90 percent white students. In 2014-15, there were 50 such schools – and at five of those schools, white students made up less than half the student body.

“When arrivals started arriving in Lewiston, roughly around 2000, there was no crystal ball about what was coming. Nor were there any programs in place, or any awareness of what programs would be needed,” said Lewiston Superintendent Bill Webster.

‘LEWISTON’S FUTURE IS MUCH BRIGHTER’

The new student demographics have been welcomed as the state’s population ages and officials fear the impacts of a growing shortage of workers. A 2016 report from the Maine Development Foundation and state Chamber of Commerce similarly said the economy will suffer if Maine fails to attract, integrate and train more immigrants.

According to that report, new immigrants and their children are expected to account for 83 percent of the growth in the U.S. workforce from 2000 to 2050.

“Our first influx of ELL students are now graduating from college and entering the workforce, and a number of them have been very successful. I want to encourage more of them to go into teaching and education as a profession and, at some point, to return to Lewiston and teach,” Webster said.

That’s one of the state’s top priorities, too, said a Maine Department of Education specialist who works with districts on issues involving English language learners.

“We’re putting a lot of energy into how to bring new Mainers into education,” said April Perkins. “New Mainers are an amazing pool of people in our state and contribute to our education system in really important ways,” such as linguistic and cultural knowledge.

Webster said he’s seen a change in downtown Lewiston, fueled by entrepreneurial immigrants.

According to U.S. Census data, the number of foreign-born immigrants living in Maine increased by about 8,000 people between 2000 and 2015. Over the same period, the number of Mainers born in Africa increased from 1,067 people to 5,791.

“I think Lewiston’s future is much brighter because of the influx. That doesn’t mean there aren’t challenges,” Webster said. But he can see the influence in the wider city. In recent months, three immigrants ran – unsuccessfully – for the school committee. A street that was previously full of shuttered businesses is now a mix of ethnic groceries, restaurants and other open businesses. There are approximately 7,500 immigrants in Lewiston.

“I find it quite exciting to see,” Webster said.

IMMIGRANTS ‘REALLY VALUE EDUCATION’

In the school system, the immigrant population is seen as more highly engaged than traditional families, with a sharper focus on academic success.

“Immigrants see education as their ticket to the American dream,” Webster said.

“In all my years, I have heard more thank-yous from the Somali families than anyone else,” Adams said. “They really value education.”

Lynn Adams, a kindergarten teacher for more than four decades, answers pupils’ questions at Longley Elementary School in Lewiston. The immigrant families she has interacted with “really value education,” Adams says. “In all my years, I have heard more thank-yous from the Somali families than anyone else.”

That is a change from earlier years in Lewiston, which saw a rash of anti-immigrant violence soon after 2000 when thousands of Somali immigrants arrived. In 2002, the mayor sent a letter to the Somali community asking them to discourage their friends and family from moving to Lewiston, saying, “Our city is maxed-out financially, physically and emotionally.”

Then an out-of-state white supremacist group seized upon the upheaval to hold an anti-immigrant rally. Three years after the rally, a pig’s head was thrown into a local mosque. The act was widely condemned, the governor at the time visited Lewiston to denounce the act, and police quickly charged the perpetrator.

That level of angst and anger has passed, Webster and others say.

For school communities, a diverse school setting is now seen as a learning opportunity.

“What a richness of experience that is for all of our students,” said South Portland Superintendent Ken Kunin. About 25 percent of South Portland students today are not white. “Our students are growing up in Maine, but they are getting an experience that prepares them to work in a diverse world. We see that as a tremendous advantage,” Kunin said.

Kunin, who experienced the first wave of immigrant students as a principal in Portland, said immigrants started moving to South Portland in recent years when the cost of living in Portland got too expensive. But that’s starting to change.

“We’re losing families to Westbrook because there is more housing there,” Kunin said.

‘WHY PEOPLE COME TO PORTLAND’

Westbrook saw its percentage of white students drop from 95 percent in 2000 to 77 percent in 2014, according to the data.

Schools have to hire teachers for English language learners and provide space for ELL instruction. In districts with a large number of ELL students, they may need ELL directors or coordinators, or hire translators.

In Portland, for example, one in four students is an English language learner and the district has a multilingual and multicultural center that provides translation services, a family welcome center to centralize paperwork and a college preparation program tailored for multilingual students. The center also holds special student financial aid nights and cultural events during the year.

Center Director Grace Valenzuela said she remembers joining the district in 1987, when there were only 150 ELL students and five other languages being spoken in the district, mostly from Southeast Asia. Today there are 1,739 ELL students who come from homes where about 60 different languages are spoken.

“It’s been sustained growth,” Valenzuela said. Portland, she said, has always been welcoming for immigrants and the district’s programs reflect a close partnership with immigrant families.

“I think that’s why people come to Portland and that’s the reason they stay,” she said.

Substitute teacher Zainab Hussein, center, supervises in the Longley Elementary School cafeteria last week. “When arrivals started arriving in Lewiston, roughly around 2000, there was no crystal ball about what was coming. Nor were there any programs in place, or any awareness of what programs would be needed,” said Lewiston Superintendent Bill Webster.

SHIFTS AT PORTLAND AND DEERING

But the demographic shift has played out differently at Portland’s two largest high schools, where students can choose to attend any high school no matter where they live.

Traditionally, Portland High School in downtown Portland has been the most ethnically diverse. But the percentage of black students at Deering High, located off the peninsula, increased from 2 percent in 2000 to 28 percent in 2014 – a 1,300 percent increase. Valenzuela said she believes that’s because Deering has adopted a new global competency model, a schedule that allows in-depth study of a few subjects at a time, and a new agreement with the Metro bus system that allows students to ride city buses for free, easing transportation issues.

At Portland High School, the percentage of black students didn’t even double during that same period, going from 14 percent in 2000 to 23 percent in 2014.

Portland’s neighborhood elementary schools reflect the demographics of their local neighborhoods.

The local elementary school in the traditionally diverse Munjoy Hill neighborhood – Jack Elementary in 2000 and East End Community School in 2014 – saw its black student enrollment quadruple from 10 percent in 2000 to 40 percent in 2014. But the whitest elementary school – Longfellow Elementary in the Deering Center neighborhood, next door to Deering High – saw its black student enrollment barely budge from 3 percent in 2000 to 5 percent in 2014.

Noel K. Gallagher can be contacted at 791-6387 or at:

Twitter: noelinmaine

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.