CUMBERLAND — Inside the unfinished basement of Dean Rock’s house, where the only natural light comes in through a pair of transom windows, a 3D printer whirs.

A shape slowly begins to form out of tiny layers of filament known as polylactic acid, or PLA, It looks like a hollow tube about 4 inches in diameter.

When it’s done, the shape will resemble a forearm, which will then be combined with a hand – also made by Rock’s 3D printer using the same polymer material – to create a prosthetic arm.

The arm is not mechanical, but when attached to the residual limb of an amputee, it is both functional and natural-looking, two things that matter a great deal to the eventual recipients.

Most of the prosthetics made in Rock’s basement so far have ended up in the Dominican Republic, where machete violence has left many without limbs and where the stigma of being an amputee is as great as the disadvantage of being without the appendage itself.

“I guess it’s pretty cool to think about it in those terms,” said Rock, a 69-year-old retired substance abuse counselor turned stay-at-home dad.

Since he first bought a 3D printer as a hobby a few years ago, Rock has joined e-NABLE, a growing network of volunteers who use open-sourced programs and templates to create prosthetics.

Rock is the only such volunteer in Greater Portland. Last year, he partnered with the Portland Rotary Club on its 3H Project, an international service effort in the Dominican Republic. He made 14 custom prosthetics for amputees in the Dominican, where most people would never be able to afford one.

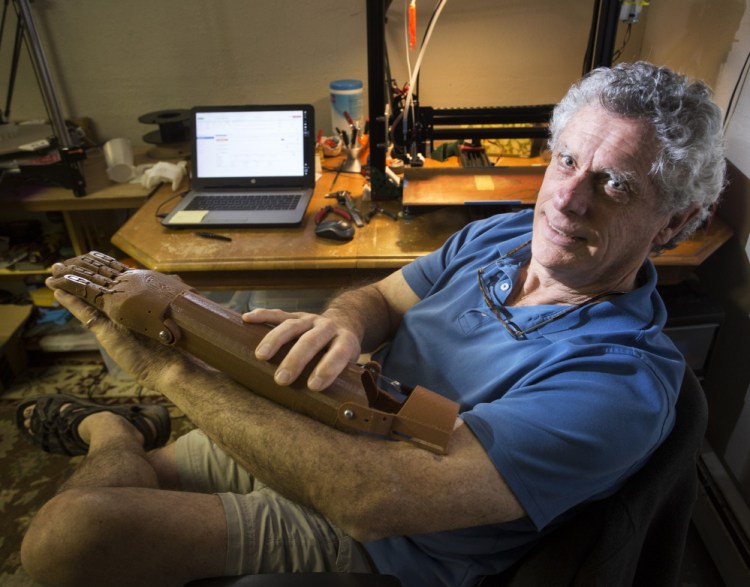

Dean Rock, who volunteers time and money to create prosthetic hands and limbs using a 3D printer in the basement of his Cumberland Center home, demonstrates the movement capabilities of one of his unfinished prototypes.

John Curran, vice president of the Portland Rotary, said the 3H Project has included prosthetics since 2012 but previous limbs were a little rough and could not be customized.

“Then we learned that there were people making these prosthetics using 3D printers and there was a network of them,” he said. “We sent an email asking, ‘Is there anyone doing this near us?’ They pointed us to Dean.”

Rock will join Curran and other Rotary Club members on a follow-up trip in January, with the goal of fitting many more people with prosthetics.

The Rotary Club also connected recently with a doctor from Kosovo, currently training in Boston, about replicating the project in his home country.

The idea that prosthetic limbs could be manufactured from easy-to-obtain materials in someone’s basement was far-fetched even five years ago. But 3D printers, which allow people to manufacture a wide range of items on a small scale, have opened up opportunities.

Some people use 3D printers for fun or for profit. Some use them in less savory ways, like making illegal firearms. But every so often, people use them for something truly good: Rock makes no money from his prosthetics and uses his own money to buy all the supplies.

“My wife and I just thought, it’s a great way for us to do a little bit in this world,” Rock said.

Dean Rock volunteers his time and money to make prosthetic hands using this 3D printer in the basement of his Cumberland Center home. The manufacuring process for one piece can take over 20 hours.

A HOBBY THAT BECAME A GIFT

Rock spent his career as a substance abuse counselor, mostly in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where he had a private practice. When his wife, a physician, got a residency in Portland, he closed the practice and became a stay-at-home dad to their son, who is 11.

They have lived in Cumberland Center for the last six years, in a traditional Cape-style house at the end of a dead-end street.

Rock needed a hobby and settled on 3D printing. Like other neophytes, he started by making small objects – knick-knacks that had little practical value other than to show off to friends.

Then, on an online forum for other amateur 3D printers, Rock learned about e-NABLE. Once he loaded the software and began messing around with designs, he was hooked. All the supplies he needed could be ordered online and were inexpensive: A $20 spool of PLA filament could make as many as four prosthetics. He had Amazon Prime, so shipping was free.

Not long after Rock joined e-NABLE, the Portland Rotary Club started looking for better prosthetics. Since 2012, the member organization’s international service project has been assisting residents of the Dominican Republic in three areas – providing hearing aids, water (H2O) filtration systems and prosthetic hands.

Curran, who has been heavily involved with the project, said connecting with Rock was serendipitous, and Rock, who had grown tired of using his 3D printer for frivolous things, jumped at the chance. He began trying out different templates and designs offered through e-NABLE. The first few attempts were rough, but he enjoyed tinkering and making adjustments.

“I’ve gotten pretty good, but there’s always something that can be changed or refined. That’s part of the fun,” he said.

Printing the prosthetics alone in his basement was one thing, but for Rock, the real eye-opener was visiting the Dominican Republic.

Long before he was involved, the Portland Rotary Club built a relationship with Hospital General El Buen Samaritano in La Romana, a resort community on the island’s southern coast. La Romana’s resorts include the expansive luxury golf destination Casa de Campo, but it also has numerous batayes – slum-like villages where many who work in the sugar cane fields live.

The fields are scattered throughout the island, and the workers wield massive machetes all day. Those same machetes are often a weapon and have contributed to a high number of people whose hands or arms have been amputated.

Many simply go without prosthetics, while others make do with what is available. But there is great stigma in the country about losing a limb.

“The assumption is that if you don’t have an arm, you must be a thief,” Curran said, referring to the practice of thieves having their hand cut off as punishment for stealing.

Since he first started printing prosthetics, Rock has made changes meant to take that stigma into consideration. His first models had an open forearm piece, which didn’t look natural. They were also made with black filament, which didn’t match the skin tone of recipients and made them stand out. Now, the prosthetics are brown – or white, which can then be painted – and the forearm pieces are closed all the way around to look more like a forearm.

“One of the men just broke down crying when we were there. I had this feeling of ‘wow, his life is so hard,’ ” he said. “You forget how hard things are in other parts of the world.”

‘THE NEED IS TREMENDOUS’

Curran, Rock and others from the Portland Rotary were already planning a return trip to the Dominican when a recent connection with a Rotarian from Kosovo presented a new opportunity.

Dr. Gani Abazi, who has been studying and working in Greater Boston for the last 10 years, had been trying for some time to get a teenager in his home country fitted with a prosthetic.

Abazi had met Portland Rotary member William Dunn, who had spent time in Kosovo when he was an electric power industry consultant.

Dunn said they should work together on a service project and the conversation steered toward prosthetics. In Kosovo, the demand for artificial limbs is as great as it is in the Dominican Republic. Many of the amputees lost hands or arms during that country’s war in the late 1990s, and although the country gained independence in 2008, health care has not been a priority.

“The need is tremendous,” Abazi said. “There are no real health services at all.”

Dunn has done numerous service trips with the Rotary Club and each has opened his eyes.

“So much of the stuff we do is stuff that we Americans really don’t think about,” he said. The 3D printed prosthetics are a perfect example. “How often do you get to change someone’s life for less than $50?”

Dean Rock volunteers his time and money to make prosthetic hands using a 3D printer in the basement of his Cumberland Center home.

Already, Abazi has fitted the teenager with one of Rock’s prosthetics, just in time for her to start college.

He plans to join Dunn, Curran and other Portland Rotary members on a trip to Kosovo in April, with the aim of having a bunch of prosthetics to take with them.

“It’s wonderful to connect to this project,” Abazi said. “This is the first time something like this has happened there.”

Curran said the overseas trips have been the best part of the Rotary Club’s service projects.

“It’s extremely infectious to see what is being done,” he said.

Rock said he plans to go to Kosovo as well, although his goal isn’t really to travel the world delivering the prosthetics he made in his basement. He’d rather teach people in those countries so they can make them without his help.

Until then, Rock is happy to keep cranking out the devices from his basement in Cumberland. Each takes about 20 hours, he estimates.

As for his own investment, he hasn’t calculated it exactly, but estimates he’s spent about $4,000 to date.

“I mean, I could spend that on a golf membership,” Rock said. “As far as hobbies or charities go, this suits me.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.