Maine’s got a lawyer problem.

A rural lawyer problem, specifically. There aren’t many of them to start with, and more than 65 percent of them are over 50 years old. To combat that shortage, the state’s only law school is offering students paid summer fellowships to work in law offices in rural areas, and a state lawmaker is proposing an income tax credit aimed at attracting new lawyers to underserved areas of the state.

“It’s an access-to-justice issue,” said Rep. Donna Bailey, a lawyer and Democrat from Saco who recently submitted the bill to the revisor’s office. Bailey said the bill will be modeled on the successful income tax credit program offered to dentists who work in underserved areas. That pilot program was renewed last session and funded again.

“We’re trying to find creative ways to attract lawyers to underserved areas,” Bailey said.

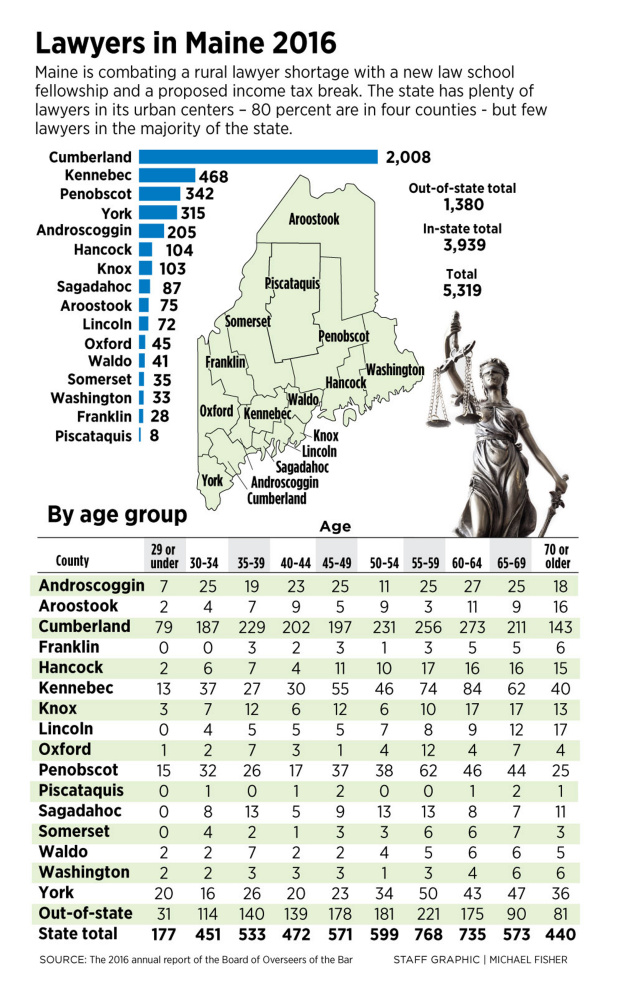

Maine has 5,319 active attorneys, and 3,939 of them live in-state. That works out to about 30 resident lawyers per 10,000 residents, lower than the national average of 40 lawyers per 10,000 residents. In New England, the per capita average is 53 lawyers per 10,000 residents.

But experts say it’s not about the per capita figures. It’s the distribution of those lawyers.

In Maine, more than half of resident attorneys – 51 percent – live or work in Cumberland County. Add in Kennebec, Penobscot and York counties and fully 80 percent of the state’s lawyers are located in just four of Maine’s16 counties.

It’s a critical problem for people who do not have access to a lawyer, said Danielle Conway, dean of the University of Maine School of Law in Portland. It’s the only law school in the state, and graduates between 70 and 90 students a year.

“If people can’t access it and depend on it, then they stop depending on the law,” Conway said. “We can’t have people question the rule of law. And lawyers represent the rule of law.”

Conway launched the new “Rural Practice Fellowship” pilot program this summer, with two students paid by the school to work with attorneys in rural practices. It introduces the students to rural practice and, hopefully, to pursue a career there, Conway said.

Student Ryan Rutledge said one of the best things about the fellowship at the Bemis and Rossignol law firm in Presque Isle was the chance to work on many different areas of law. In a rural law practice, much like a country doctor’s, the lone lawyer in town has to be able to handle all the legal issues that come up, from selling a piece of land to representing a client on criminal charges.

“I have been fully immersed in everything that this firm does,” Rutledge said in a phone call during the summer, midway through his fellowship. “At the big firms in Portland, it’s all sectioned off and everyone has a role to play. Up here, there’s just a lot more going on. Because there’s not a lot of attorneys, the attorneys here have to be well versed in many areas of the law instead of just specializing.”

The fellowship has given him some perspective on what kind of job he wants after graduation.

“In Portland (law school graduates) are all fighting over the bigger firms. They’re going to be paid a little bit more, but everyone is fighting for those positions,” he said. “But I think the cost of living is so much lower and you are going to get more experience in a rural area in your first few years than you would in a firm in Portland.”

It will also mean diving right in to a full, busy career, he said.

“It’s kind of like drinking from a fire hose. You are thrown at everything a senior attorney is going to do because they need the manpower. In Portland, for the first one or two years, you’re going to be seated at a desk, doing exactly what someone tells you to do,” he said.

In addition to the summer fellowship, the students attend workshops and seminars during the school year. It is open to two students in each class, for six students total. Conway said they hope first-year students will return for second- and third-year experiences, so they will be in the program for their entire law school career. The program would be expanded if funding becomes available, she said.

Conway said the school pays fellows $6,000 the first and second year, and $7,500 the third year, easing the burden of $23,500 in-state tuition per year.

Jacqueline Rogers of the Maine Board of Overseers of the Bar said the rural lawyers shortage is an issue nationwide. Maine is just particularly hard hit since it’s a “gray state,” second only to Florida in percentage of residents over age 65.

Several states have set up similar programs to encourage more young lawyers to consider rural areas.

In Oregon, Vermont and Nebraska, the state bar awards fellowships and places law school students in rural locations during the summers. In South Dakota, where the rural lawyer shortage is so severe that the American Bar Association says there is a “very real possibility of whole sections of South Dakota being without access to legal services,” the state bar has partnered with multiple organizations, including county commissioners and local retailers, to cultivate rural lawyers.

In 2013 South Dakota drew national attention when it became the first state to pay young lawyers to relocate permanently to rural areas – up to $12,000 a year for five years – and ran a website matching lawyers with communities or with other lawyers seeking a successor.

“We need to see an influx of younger lawyers. That isn’t panning out yet,” Rogers said, noting that many lawyers in Maine will be retiring in the next five to 10 years. In Maine, 44 percent of resident attorneys are over the age of 60 and 12 percent are under 35, according to the most recent annual report of the Board of Overseers of the Bar.

Falmouth attorney Lowell Brown has long championed the need to attract young lawyers to rural Maine.

“The whole legal system really turns on whether people know what their rights are. The law is sufficiently complex now, that unless you have access to a lawyer, you can’t understand that. People’s rights are being denied to them, and not because of some grand conspiracy but because they don’t have access to the resources that allow them to participate in the justice system,” Brown said.

“That’s why I think this initiative is so important.”

Noel K. Gallagher can be contacted at 791-6387 or at:

Twitter: noelinmaine

Send questions/comments to the editors.