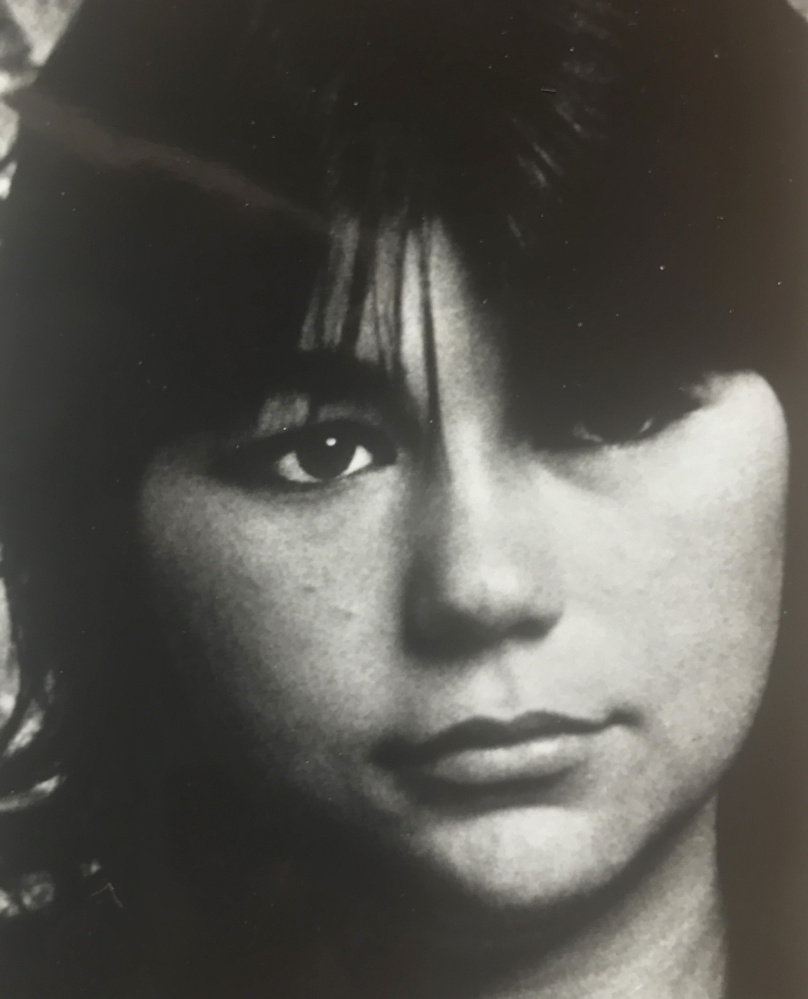

The retired Portland police detective who investigated the 1989 homicide of Jessica Briggs lashed out from the witness stand Thursday, insisting that he did not “zero right in” on Anthony H. Sanborn Jr. for Briggs’ murder.

James Daniels’ heated exchange with Sanborn attorney Amy Fairfield came in response to rapid-fire questions about his handwritten notes that listed supposed links between Sanborn and the murder. After reading aloud each item, Fairfield tried to refute it.

It was the final exhibit in Fairfield’s direct questioning of Daniels.

Sanborn was convicted in 1992 of the murder, but was freed on bail in April after a key witness recanted. He is trying to clear his name in marathon evidentiary hearings being held before Justice Joyce Wheeler.

As Fairfield went through the list Thursday, Daniels, who had appeared calm over several long days on the witness stand, began to react more forcefully.

“You’re trying to create links to Anthony Sanborn,” Fairfield said, after contradicting a few items with Daniels’ own notes and reports.

“I don’t know what I’m trying to do, you’re telling me what I’m trying to do,” said Daniels, who has asserted repeatedly that he does not remember what some notes meant. “You make a list and you look at a checklist. This points to him. If there’s things that can clear a person, you do that as well.”

But, Fairfield pointed out, no such lists of linkages existed for at least five other possible suspects – “Because you singled, zeroed right in on Anthony Sanborn,” Fairfield said.

“I did not single, zero right in on anyone,” Daniels responded.

The detective said he focused on Sanborn because people around him began to come forward with information that Sanborn had admitted to the murder.

But Fairfield said the reports of second- and third-hand information began pouring in after Sanborn’s picture was shown across the news, and that most of the witnesses in the case were young, vulnerable street-kids.

“And you and Danny Young played good cop, bad cop with these kids, right?” she asked in her final question.

“No, we never did that,” Daniels said.

But less than a week ago, Daniels’ partner, Daniel Young, testified that the two investigators used exactly those tactics when interviewing a teenage witness, David Schwarz.

“I screamed at (Schwarz) trying to be the bad cop, so to speak, trying to get him to stop holding back,” Young said during testimony on Oct. 13.

Now the state will get its chance to cross-examine Daniels.

At the heart of the case are allegations by Fairfield that police withheld exculpatory information from Sanborn’s original defense team, contrary to a legal principle that requires police to turn over such details. Failing to do so is considered a violation of a defendant’s constitutional rights to due process and a fair trial.

Fairfield has focused on a trove of Sanborn case files that Daniels kept in his home for decades after retiring, and has worked to show whether information found in the handwritten documents were faithfully transferred to typewritten reports that were then handed over to the defense.

Daniels, who retired in 1998 after 22 years as a police officer, has struggled to come up with independent recollections of events that occurred nearly 30 years ago.

He has been forced to rely on his notes and reports in a laborious process to discern the meaning of what he wrote half a lifetime ago.

The heated exchanges Thursday came after a round of questions about a potential alternate suspect, Morris “Butch” King, who knew the 16-year-old victim and was angry Briggs had refused to be a prostitute for him and had broken up with him.

Daniels read from his notes about meeting with multiple people who described King and said he “went” with Briggs.

But in an official report that was turned over to Sanborn’s original defense team, King told investigators he did not know Briggs, and the record was never altered to reflect the information in Daniels’ handwritten notes.

“What ruled him out?” Fairfield asked.

“Nothing ruled him out, we just didn’t build a case against him,” Daniels said.

“And you have three instances in your notes saying Morris ‘Butch’ King knew Jessica Briggs, and we have a report saying that he didn’t know her.”

“Yes,” Daniels said.

Although the hearings were originally scheduled for 12 days and would end next Wednesday, the clerk’s office at Cumberland County Unified Criminal Court is holding Courtroom 8 for the Sanborn hearings indefinitely, or until Wheeler leaves for vacation on Nov. 17.

The length of the proceedings is unusual.

Wheeler indicated fatigue with the slow course of the hearing, and has asked the attorneys during witness testimony to speed along the admission of documents into evidence.

“I don’t know about anyone else, but I’m wiped,” Wheeler said, after she ascended the bench just after 9 a.m.

So far only two witnesses – Donald Macomber, one of the original prosecutors on the case, and Glenn Brown, a friend of Sanborn – have completed their testimony.

The rest of the time has been absorbed by the painstaking testimony of the retired detectives.

Still yet to testify is then-Assistant Attorney General Pamela Ames, the lead prosecutor during the 1992 trial, who is expected to begin testifying Friday.

Ames is now an attorney in private practice in Waterville.

She maintains that Sanborn’s conviction was proper and that he was guilty of the murder.

Matt Byrne can be contacted at 791-6303 or at:

Send questions/comments to the editors.