BOOTHBAY HARBOR — The slain American Nazi leader whose career and writings inspired leaders of today’s neo-Nazi movement was raised near this seaside town, graduated from Hebron Academy, and ran advertising and publishing businesses in Portland and Boothbay Harbor in the decades prior to becoming an advocate of industrialized mass murder and the forced deportations of non-whites.

George Lincoln Rockwell founded the American Nazi Party in 1959 and with his few dozen followers elbowed his way onto the front pages of newspapers across the country by staging hate-themed rallies and marches, complete with Nazi flags, armbands, and calls for the gassing of Jews and the hanging of communists and alleged traitors to the ambitions of an imagined “master race.”

After decades of obscurity, Rockwell’s legacy burst back into the national spotlight after last month’s neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, some of whose leaders have called him their movement’s “grandfather” and adopted a phrase he coined, “white power.” A half-dozen members of the successor to his party staged a vigil Aug. 25 in Arlington, Virginia, on the site of his murder by one of his followers 50 years before.

“He’s the most important figure in the white supremacist movement since World War II,” says Heidi Beirich, who tracks hate groups as director of the intelligence project at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama. “His original organization spawned the movement’s most important organizations until very recent times, and his ideas remain central to what is going on right now in the movement.”

Rockwell’s contributions, Beirich says, include the creation of Holocaust denial, the idea that white people should have their own “ethno-state,” and the expansion of the Nazi definition of “whites” from certain northern and central European ethnicities to nearly all Europeans, including Slavs, Greeks and southern European Catholics, whom Hitler himself held in dim regard. “Without Rockwell, you wouldn’t have what we see today,” she says.

Marilyn Mayo, a senior research fellow at the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism, says neo-Nazi groups still venerate him, while his tactics have been adopted by an even broader swath of white nationalist groups. “He wanted to get his ideas mainstream attention by staging events that would draw media attention, like rallies or speeches on college campuses,” Mayo says. “His tactics have great resonance today.”

In the 1960s, former Maine neighbors, friends and classmates were surprised to discover the energetic and sociable young man whom they had known in the 1930s and 1940s was praising Adolf Hitler, driving a vehicle labeled “the Hate Bus” through the South to oppose civil rights, and calling for African-Americans to be deported en masse.

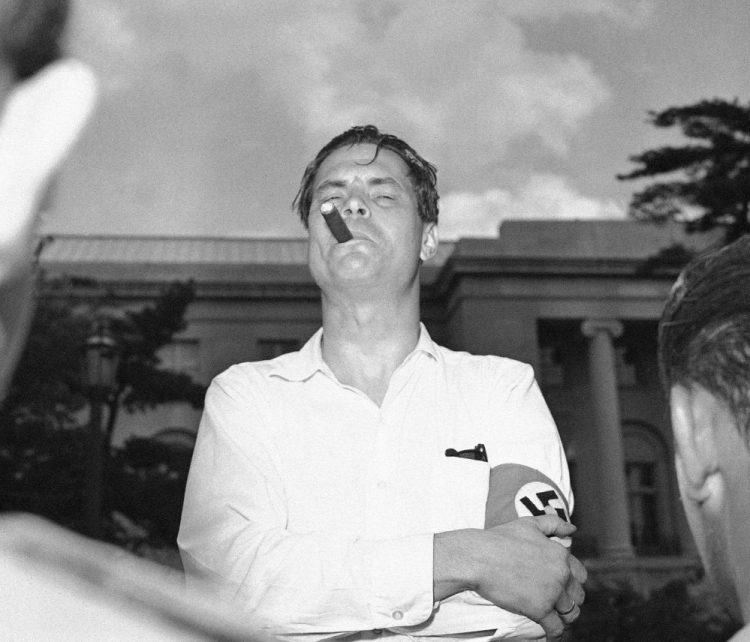

George Lincoln Rockwell, center, self-styled leader of the American Nazi Party, and his “hate bus” bearing several young men wearing swastika arm bands, stops for gas in Montgomery, Ala., May 23, 1961, en route to Mobile, Ala.

“I recall Linc as a happy-go-lucky fellow, a real good egg,” one unnamed Portland friend told the Press Herald in 1960, when word of Rockwell’s effort to revive Nazism reached Maine. “He was an extrovert all right, but I don’t believe he ever expressed any political ideas or was bigoted in any way.”

SON OF VAUDEVILLIANS

Rockwell was born in Illinois in 1918, the son of famous vaudevillian comedians Claire and George “Doc” Rockwell, who were friends with Groucho Marx, Fred Allen and Benny Goodman. His parents divorced in 1924, and the young Rockwell spent school years with his mother in Atlantic City and summers with his father on Southport, where the elder Rockwell moved full time during the Great Depression.

Rockwell wouldn’t embrace fascism until after leaving Maine, but in his autobiography he described several Maine experiences as formative. First was his alleged love of the reckless and difficult, which he first expressed in dangerous sailing trips in a small open boat.

“I preferred to go out when the others came in because the wind was ‘too strong,’ ” he recalled before describing a round trip from Southport to Pemaquid Point that required tacking up the narrow passage known as the Thread of Life in darkness, heavy winds, and against the tide. “I am now fairly certain that the driving force in my life is a deep satisfaction in defying any overwhelming odds which seem to press against that which I will.”

This characteristic, he continued, would help propel him to the White House. (He ran in 1964 and got 212 write-in votes nationwide.)

His father’s Jewish visitors on Southport, Rockwell wrote, cultivated his anti-Semitism, particularly radio comedian Fred Allen’s wife, Portland Hoffa, and big band leader Benny Goodman. Hoffa’s transgression was to have “used the Anglo-Saxon word for body waste to express her distaste for some idea” in their parlor, which shocked the teenager. Goodman’s was to have left their company after just one evening because, in Rockwell’s view, he couldn’t stand the peace and quiet and “scurried back to the soul-destroying hothouse life of New York City with his millions of Jews.”

His parents, he said, may have injected “some slight vestige of prejudice into my upbringing, but no more than in the upbringing of millions of other American boys who are not leading Hitler movements.” His father later would cut off communication with him, appalled by his embrace of Nazism.

After Rockwell graduated from Atlantic City High School, his father enrolled him at Hebron Academy for the 1937-38 school year, hoping it might help him gain admission to Harvard. There he found two Boothbay Harbor friends, Eben Lewis (who had joined him on the epic Pemaquid sail) and Stanley Tupper, who would go on to represent Maine in Congress. There he and Lewis organized what he would later term “my first tiny political organization”: a mob that terrorized an especially strict chemistry professor by burning him in effigy, marching around the Hebron campus with torches and signs and leaving “impudent notes.” The professor quit at the end of the school year.

Classmate John Hahn, who became a reporter for United Press International, later recalled Rockwell as “a tall, skinny teenager who – even then – smoked a pipe, had a lot of odd ideas, trained mice, and loved classical music.” Hahn was the yearbook editor at Hebron, and described him there as “the loudest talker on campus and the originator of more weird theories than anyone else,” but later said he couldn’t “equate anything in particular” Rockwell did there with the hate leader he would become.

Rockwell was accepted at Brown University but left to serve as a naval aviator in World War II, primarily in the Pacific theater. After the war, he enrolled at the Pratt Institute, a commercial arts and design school in Brooklyn, but became fed up with New York’s diversity, which, to his disgust, included people of mixed race. “The ‘melting pot’ has turned out to be more of a garbage pail,” he complained. He dropped out of Pratt in 1947 and returned to the relative homogeneity of Boothbay Harbor, where he operated a studio for photo developing, portrait drawing and sign painting. (“It was a wonder to me that more photo-finishers do not get tempted into blackmail schemes,” he later observed.)

Rockwell, now married with a child to support, started Maine’s first advertising agency, eventually persuading Al Bonney and Norton Payson to invest in the venture. Maine Advertising Inc., with offices at 53 Exchange St. in Portland, later reorganized into the Simonds Payson Co., but by then Rockwell was long gone.

Rockwell, who had been living in Lewiston while working as art director for the advertising agency, moved his growing family to a cottage in Falmouth Foreside in 1949 and started the Rockwell Publishing Co. The tourist guide he published, the Olde Maine Guide, was modestly successful – the Press Herald published a picture of Rockwell and then-Gov. Frederick Payne holding a copy together in May 1950 – but it wasn’t paying the bills. “The financial struggle to stay alive was deadly, and my family lived in … the most heartbreaking poverty and misery,” he recalled. His wife left him, taking their two children to her mother’s home in Connecticut.

Then, one night in that cottage in the summer of 1950, he heard a voice on the radio that changed his life.

“It seemed like a voice from another planet – a wonderful, patriotic, American voice – a voice which almost seemed to come from inside myself,” Rockwell later wrote. “I whooped and hollered for Joe McCarthy!” Sen. McCarthy had started his hyperbolic campaign against alleged Communist infiltration of the federal government, and Rockwell was transfixed.

As he later told it, he soon got in his car and drove, alone, from Falmouth to San Diego, to “start the career which has led me so far to embattled notoriety all over the Earth, and which will one day place me at the head of millions of Americans who now hate me and all I stand for.”

RADICALIZED BY MCCARTHY, ‘MEIN KAMPF’

In reality, the Korean War had begun and he had been again called up for service. But while training in San Diego he became radicalized, reading the fabricated “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” and Hitler’s “Mein Kampf,” which convinced him that almost everything he found bad in the world – the Soviet Union, communism, democracy, racial equality – was part of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy.

In November 1952, he was assigned to the naval air station at Keflavik, Iceland, where he met his second wife, Thora Hallgrimsson, a member of one of the country’s most powerful families and a niece of Iceland’s ambassador to the United States. She followed him to his final assignment at Brunswick Naval Air Station, and they lived in a cottage on Bailey Island in late 1954 and early 1955, where he conceived of creating a glossy magazine for the wives of servicemen, US Lady.

They moved to Washington, D.C., so he could pursue this dream, but when the publication failed to make money, Rockwell threw himself into hate politics full time. He set up an anti-Jewish organization and then, in 1959, the American Nazi Party. Horrified, Thora’s family brought her and their three children back to Iceland. (Today she is the wife of disgraced former billionaire Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson, chairman of Landsbanki, a bank whose 2008 collapse helped bring down Iceland’s economy.)

Flanked by his followers, American Nazi Party leader George Lincoln Rockwell addresses the media in Arlington, Va., on Nov. 3, 1965. Rockwell had deep Maine ties, living and working here for decades.

Over the next three years, Rockwell did his best to draw attention to his tiny party, which rarely had more than a few dozen active members. He held a rally on the Washington Mall, spoke at unfriendly college campuses, drove his “Hate Bus” through the South railing against racial mixing, and was pelted with stones by Holocaust survivors as he and his men picketed the Boston premiere of “Exodus,” a movie about the creation of Israel, in their storm trooper regalia. (“I was at Auschwitz – I lost my whole family there,” 39-year-old Icek Wluka told reporters. “We must stop this before it spreads.”)

He returned to Portland on Memorial Day 1966 in a swastika-festooned black Lincoln Continental convertible to toss a wreath from East End Beach to honor “white Christian fighting men.” The Press Herald reported that Rockwell proceeded under police escort and that a crowd of 300 watched the proceedings in silence from the bluffs above the beach but subjected Rockwell and his handful of fellow Nazis to “a gauntlet of boos and catcalls as they returned to the promenade.”

It was his last trip to Maine.

A May 31, 1966, clipping from the Portland Evening Express chronicles George Lincoln Rockwell’s final visit to Maine.

‘A TIGER BY THE TAIL’

The following year, Rockwell made a surprise visit to U.S. Rep. Stanley Tupper’s Washington office, the first time they’d seen each other since Rockwell’s turn to radical politics. “I could simply not help asking, ‘Why, Linc, why?” Tupper recalled in his own memoirs. “He grinned and spread his hands and said, ‘If I said I hate Jews and Negroes, people would say ‘so what,’ but when I praise Hitler they go crazy.’ And then, leaning toward my desk he said, ‘Tup, I’ve got a tiger by the tail and I will be killed.'”

“I’m not a psychiatrist,” Tupper added, “but it would seem that his lifelong need for attention was so strong that it finally did not matter how he got his attention.”

On Aug. 25, 1967, Rockwell was shot and killed outside a laundromat in Arlington, Virginia, by an estranged member of his group. “I’m not surprised at all. I’ve expected it for some time,” his father said softly when a reporter informed him of the murder. “I think he would have liked to have gotten rid of the whole Nazi mess. He was more afraid of his own men than people were of him,” he added.

His father arranged for his son to be buried in Maine, but the Arlington-based American Nazi Party seized his remains, ultimately cremating the body after half a dozen cemeteries turned them away.

Last month The Washington Post quoted a leader of one of the American Nazi’s successor group as saying they still had his ashes in an ivory urn. “We want to keep them in a secure location until a time when we can inter them properly,” Martin Kerr of the New Order group told the paper. “We’re not at the end of the Rockwell wave; we’re at the beginning.”

Colin Woodard can be contacted at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.