PORT ARTHUR, Texas – The water was leaving, at last. But, across southeast Texas on Thursday, new dangers kept appearing in Hurricane Harvey’s wake.

In Crosby, northeast of Houston, loud “pops” were heard coming from a crippled chemical plant, where safety systems were flooded and authorities said an explosion could be imminent.

A fire burns Thursday at the flooded Arkema SA chemical plant in Crosby, Texas. The plant’s safety systems were flooded and authorities said it could explode.

In Beaumont, 118,000 people were without drinking water after floods disabled the city’s system. For most of them, there was no easy way out of a town that now felt like more of an island: The city was surrounded by swollen rivers and bayous, cutting off most roads.

Forty miles to the southwest, in Anahuac, the employees of an alligator farm circled their flooded property in boats, with guns at the ready. There were 350 alligators inside, and their pens were flooding. “They were very close to getting out,” a police officer said.

Above, Environmental Protection Agency planes sniffed for toxic-chemical releases. Below, there was floodwater that authorities warned could contain pollutants and pathogens. In between, there were authorities and regular people trying to find order and supplies in a landscape totally changed by the massive storm.

“We’re running low on water and on food,” said Lam Nguyen, a Port Arthur police sergeant who was overseeing a command center in a Walmart parking lot. He was wearing a red polo shirt instead of his usual police uniform, which was lost when his home flooded. “Our shelters are filling up. We are getting them food, for now, but we are running out of food. We’re doing all we can now.”

A Black Hawk helicopter landed nearby every 30 minutes, bringing in newly rescued people. Nguyen paused.

“We are in trouble,” he said.

The remnants of Harvey were still moving to the northeast Thursday. Even in a weakened state, the storm caused flash-flood watches in Tennessee, Kentucky and southern Ohio. Behind it, authorities continued to try to assess the damage left by the largest rainstorm ever to hit the continental United States. On Thursday, an official with the Harris County Flood Control District gave an astounding estimate of the storm’s impact on the Houston area: at the height of the flooding, 70 percent of the county’s 1,800 square miles were covered with at least 1.5 feet of water. That is an area larger than Rhode Island.

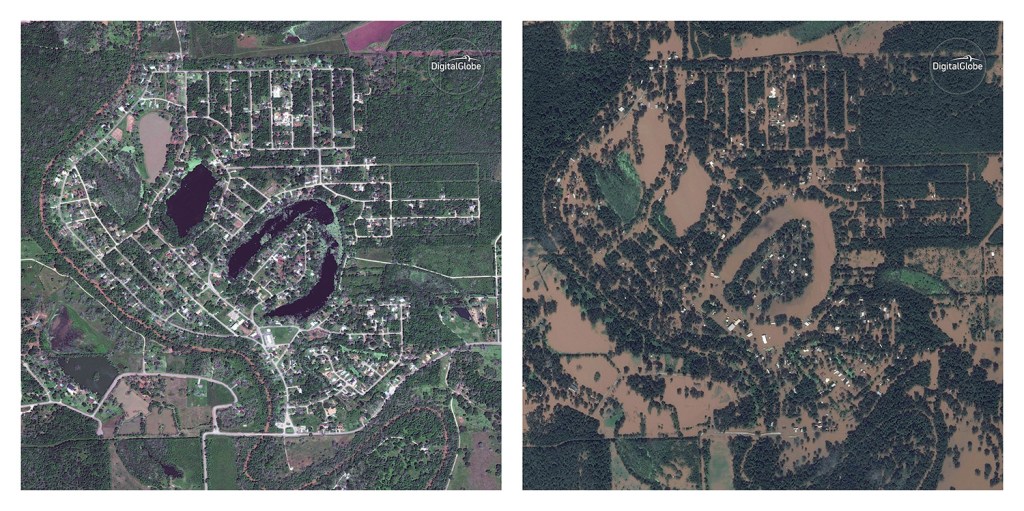

This combination of satellite images provided by DigitalGlobe shows Simonton, Texas, west of Houston, on Nov. 20, 2016, left, and on Wednesday, after Harvey inundated the area.

At least 39 people were dead. They included Andrew Pasek, 25, who officials said was electrocuted when he stepped on a live electrical wire in the floodwaters, and Ronald Zaring, 82, an evacuee who became unresponsive while on a charter bus carrying him away from the flooding. Police in Houston began to make house-to-house searches, looking for more victims.

At least 34,000 people were scattered among dozens of shelters. Two huge convention centers. Mosques. Schools. At least 11 First Baptist Churches in 11 small Texas towns.

Authorities also were still tallying homes damaged or destroyed in the disaster. Texas localities had reported by Thursday that more than 93,000 homes suffered damage, including nearly 7,000 that were destroyed by Harvey, according to a Texas Department of Public Safety report. But that preliminary estimate does not include figures from heavily populated Houston and other cities that were hit hard by flooding, such as Port Arthur and Beaumont. The real number is likely to be far higher once authorities are able to assess areas that are currently unreachable.

On Thursday, thousands of people – the luckier ones – went back to homes that were waterlogged but salvageable.

“We raised up everything,” said Susan Rath, who had returned to a home in south Houston where she and her husband, Jim, had tried to place valuables higher before evacuating. The water got higher still. They returned to soggy drywall, destroyed furniture and a closet full of blouses soaked up to the elbow. “It didn’t matter.”

The Raths had just rebuilt this house, after it was destroyed in a 2015 flood. Now, they will have to decide whether to rebuild again.

“The main thing is: This is just stuff,” Jim Rath said. “And the more stuff you have, the more you’re controlled by it.”

Vice President Mike Pence visited Texas on Thursday, stopping in Rockport and Corpus Christi, and touring the affected area by helicopter. He met with Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, R, who declared this Sunday a “day of prayer in the state.” Pence also cleared storm debris in Rockport, near where Harvey first slammed ashore.

“We will be here today, we will be here tomorrow, and we will be here every day until this city and this state and this region rebuilds bigger and better than before,” Pence said. On Thursday, the Federal Emergency Management Agency said it had distributed more than 2 million meals and 2 million liters of water. Of the recovery effort, Pence said, “It’s a long way to go; it’s not months, it’s years,” adding that the challenges are “great.”

Also, White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said that President Donald Trump would donate $1 million of his own money to help with hurricane relief efforts. Sanders said that Trump wants the news media to choose which charity receives the money.

There are early indications that yet another tropical storm may form in the western Gulf of Mexico next week. Although rainfall is impossible to predict in a storm that hasn’t developed, any additional rain would be significant for the already devastated region. Not only would it affect and delay recovery efforts, but it also could lead to additional flooding – water on top of water.

“If this system does develop, it could bring additional rainfall to portions of the Texas and Louisiana coasts,” the National Hurricane Center said Thursday.

All day Thursday, authorities in Crosby watched the damaged Arkema chemical plant – which manufactures organic peroxides, a family of compounds used in such products as pharmaceuticals and construction materials.

Those chemicals must be kept cold, or they will combust. They are not cold anymore. The storm left the plant submerged in six feet of water, and its cooling systems and backup systems failed.

Now, everyone within a mile and a half of the plant has been ordered to evacuate. On Thursday, there were reports of pops and “intermittent smoke” coming from the compound. It was unclear whether that was the worst of it, or just the start.

An explosion at the plant could release a plume of the chemicals, which have been classified as skin and eye irritants. William “Brock” Long, administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, called the potential for a chemical plume “incredibly dangerous” at a briefing Thursday morning.

Already, the Harris County Sheriff’s Office said that one deputy was hospitalized after inhaling fumes from the plant, while several others sought medical care as a precaution.

Police and the Coast Guard were still rescuing people from the water there, under blue skies. Haley Morrow of the Beaumont Police Department said that about 700 water rescues had been made in the city in recent days.

Then the water went out.

The city lost access to running water after 2 a.m. Thursday, when floodwaters overwhelmed the pumping system through which the city draws water from the Neches River into its treatment facilities.

“When you take water out of the picture, people start to panic a bit,” Morrow said.

Morrow said that city officials were scrambling to find a temporary solution to the absence of running water, and to assure residents that help was on the way. They were hoping for a water delivery from the outside, but weren’t sure when it would arrive.

Those hoping to leave Beaumont found they were on an island, surrounded by murky water. Police said some people who tried to leave anyway were turning around upon discovering that the exit was impossible, driving the wrong way on U.S. Highway 90 to return.

In nearby Port Arthur, an ad hoc volunteer operation was set up to bring people from flooded homes to a new shelter at a bowling alley.

“It’s been chaotic, to say the least,” said Mason Simmons, a mechanical engineering student at Lamar University, standing with a group of friends and family members on the curb of Max Bowl. They were pitching in to help people off boats and out of pickup trucks.

This combination of satellite images provided by DigitalGlobe shows Holiday Lakes, Texas, south of Houston, on April 3, left, and on Aug. 30, five days after Hurricane Harvey made landfall and brought historic rainfall.

Simmons said he has seen hundreds of people in the roughly six hours he had been at the bowling alley.

Someone nearby said one boat rescued 60 people.

Inside Max Bowl, some people slept at the edge of bowling lanes. Luggage and plastic bags filled with clothing competed for space with racks of bowling balls.

“I think the most incredible part is it’s been community organized, really,” Simmons said. “There’s no one person leading anything. We’re just doing what we can.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.