A statewide shortage of nurses has injected a tough new challenge into Portland’s efforts to contain millions of dollars in annual overtime spending, and the city is looking to new immigrants as a possible part of the solution.

With chronic staff vacancies at the city-run Barron Center nursing home, Portland spent more than $1 million on overtime for nurses in 2016. That is about as much as the city spent on overtime for police officers and for firefighters, two groups that have been the focus of city efforts to contain OT costs.

In response, the city has intensified its efforts to recruit and train certified nursing assistants by targeting new immigrants and low-income workers looking for new careers.

Ed Latham, director of nursing at the center, said there are about 600 CNA vacancies statewide, creating an especially acute problem for nursing homes such as the Barron Center.

“It takes a special kind of person to do this job,” Latham said. “You have to get something out of caring for elders, or you wouldn’t be able to do the job for any amount of money.”

OVERTIME REDUCTIONS

The nursing shortage adds a new wrinkle to what has been a recurring struggle to contain OT costs in Maine’s largest city.

Along with the annual payroll expense, overtime also costs the city in additional retirement payouts because the earnings are combined with base wages when retirement benefits are calculated. And City Manager Jon Jennings said he is concerned that excessive overtime also could lead to employee burnout and affect job performance, especially in the police, fire and public works departments.

“I’ve made it well known – we need to do anything and everything to take care of our people and to moderate overtime,” Jennings said.

Records show Portland has had some success and reduced overall spending for overtime in 2016.

In 2016, the city spent just under $4.6 million on overtime, roughly 6 percent of its $75.7 million payroll, according to a Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram analysis.

That’s down from the $5.4 million in 2015, when overtime costs reached 7.3 percent of the city’s payroll after years of steady increases. The 2016 overtime cost was slightly less than the $4.7 million spent on overtime in 2013.

Also, fewer individual employees earned more than $20,000 in overtime wages last year. In 2016, 25 employees crossed that threshold, compared to 34 the previous year.

The biggest reason for the overall decrease is the city’s success in reversing OT growth in the fire department, which in recent years has accounted for the biggest share of overtime.

Overtime spending for firefighters decreased by more than $600,000 last year, from $1.7 million in 2015 to under $1.1 million – the lowest level in the last decade. Only eight firefighters earned more than $20,000 in OT last year, compared to 21 the previous year. That reverses years of increases since 2013.

The turnaround follows steps last year by Jennings to ensure the department was fully staffed after a hiring freeze helped lead to 18 vacancies in the department in 2015. Firefighters also agreed to work the first 12 hours of overtime at straight pay to help rein in the costs.

KEEPING PATIENT COUNT BELOW 200

On the other hand, overtime costs continued to grow in 2016 for the city’s police department, the result of a struggle to fill vacant jobs.

Jennings said last month there were 15 vacancies in the police department, which is authorized for 163 sworn officers and 59 civilian employees.

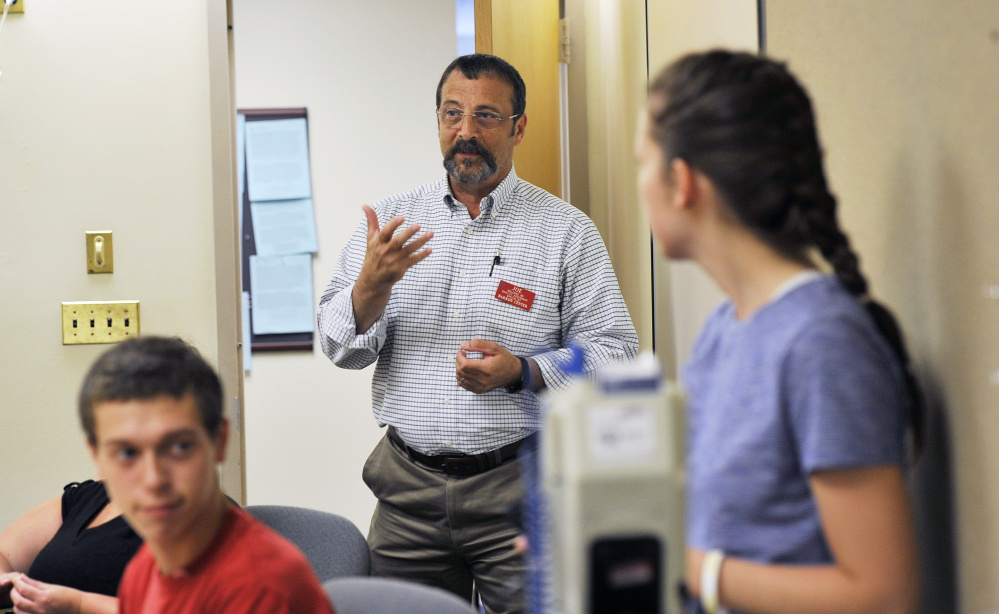

Chris Willette of Standish plays the role of a patient during the Barron Center training program. Ed Latham, director of nursing at the facility, says: “It takes a special kind of person to do this job.”

Staffing shortages pushed up the police overtime budget by $65,000 in 2016, from nearly $961,500 to over $1 million for the first time since 2013. Nine police officers made more than $20,000 in overtime last year – up from five the previous year.

Portland is not the only community struggling to hire police officers, and the city is seeking an edge by offering $10,000 signing bonuses for new recruits.

The state’s worsening shortage of nurses, meanwhile, has fueled a 27 percent increase in overtime at the city’s Barron Center in the past three years, from about $780,000 in 2013 to nearly $1.1 million in 2016.

As of late last month, there were six CNA openings and five registered nurse/licensed practical nurse openings, the city said. The center has about 250 nurses and about 100 are scheduled to work each day.

Latham, the nursing director, said the Barron Center has 219 beds available, but he keeps his patient count to below 200, simply because of the staffing shortage.

Starting pay for CNAs is $12.92 an hour, according to city officials. However, a CNA with three years experience could earn a starting pay of $15.30 an hour, plus differentials, with an on-call rate of $14.50 an hour, according to the city’s job posting. Latham said Portland’s starting pay is higher than other nursing homes.

Among the licensed nurses at the center, Olga Davydora, LPN, and Teresa Koontz, RN, are frequently among the city’s top overtime earners annually. Last year, Davydora earned $48,560 in overtime, bringing her gross earnings to $102,058, while Koontz earned $43,391 to make $104,920.

Latham said both nurses usually step up to work overtime when no other nurse is willing.

“Somebody’s got to take care of these older people, so they stay,” he said. “Those two really do work inordinately hard.”

And they’re not alone. Last year, Barron Center nurses accounted for four of the top 10 municipal overtime earners.

RECRUITING NEW ARRIVALS

Latham said CNA training courses are being held for three hours a night, three nights a week to reach people who may be working low-income jobs and are looking for another career path. Students must complete 180 hours of training in the classroom, lab and clinic to become a CNA.

Jennings said the city is looking to tap immigrants for nursing jobs. Through the city’s HIRE program, which brings together Portland Adult Education, workforce development groups and businesses, he said immigrants are being immersed in an English language course so they can be trained as nurses. After learning English, they become eligible for the CNA course, he said.

The course costs $450 per student. Those unable to pay have their tuition covered with funding from Goodwill and Coastal Counties Workforce Inc., the city said.

City officials said the first round of classes started July 17. There are nine people enrolled, including four immigrants.

“We’re very focused on making sure we have a group of people who are qualified and will be with us for a while, with a specific focus on reaching out to our immigrant communities,” Jennings said.

Randy Billings can be contacted at 791-6346 or at:

rbillings@pressherald.com

Twitter: randybillings

Send questions/comments to the editors.