A pair of warring impulses seem to drive Opera Maine, the freshly renamed company formerly known as PORTOpera (and before that, Portland Opera Repertory Theater). Members of the company’s administration will tell you that they would love to present more than a single large production every year, and they agree that, in an ideal world, interspersing recent works among the repertory staples would best serve Portland’s opera-starved music fans. That’s why the company typically presents a modern chamber opera, like this summer’s staging of Jack Perla’s thought-provoking “An American Dream,” in the weeks before the main stage offering.

The other impulse is to limit its full-fledged, high-visibility productions to enduringly popular works like Verdi’s “La Traviata,” which opened in an attractively staged production at Merrill Auditorium on Wednesday evening and will be repeated on Friday.

You can’t really blame the company for favoring the classics. Opera is expensive, and if Opera Maine’s board is unable to raise enough money to present more than one big work, offering a guaranteed ticket-seller is the fiscally responsible choice.

Whether it’s the artistically responsible choice is a topic on which reasonable listeners may disagree: It leaves the unfortunate impression that in the vast operatic canon, only 19th-century tear-jerkers are worth staging. Yet, in a city where opera productions are few and far between, works like “La Traviata” ought to be seen.

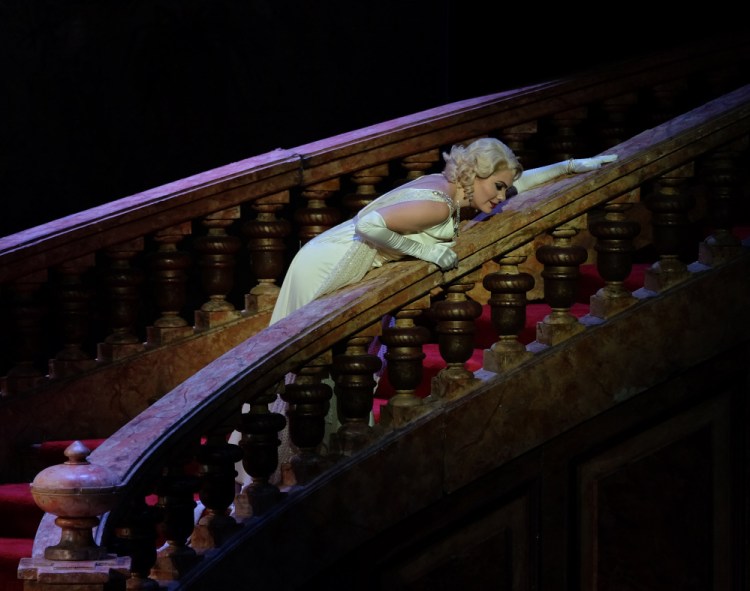

This “Traviata” unfolds on colorful, eye-catching sets, designed by Lloyd Evans (and borrowed from Opera Carolina in Charlotte), that vividly evoke the Parisian opulence that Verdi’s setting of Alexander Dumas’ semiautobiographical tale demands. Not that the staging is entirely traditional: Dona D. Vaughn, the company’s artistic director and the stage director here, moved the action into the early decades of the 20th century, with costumes by Millie Hiibel and hair and makeup design by Sondra Nottingham that suggested the party atmosphere of the Roaring ’20s.

If you don’t already know the story, Alfredo Germont, a wealthy young man, has fallen in love with Violetta, a Parisian courtesan, and the two are living an idyllic life at Alfredo’s country home when Alfredo’s father turns up to tell Violetta, without much delicacy, that his daughter cannot marry so long as Alfredo is involved with a woman of ill repute.

Implausibly, by today’s standards, Violetta agrees to give up Alfredo and returns to Paris, where Alfredo, unaware of the discussion between his father and girlfriend, tracks her down at a party and showers her with recriminations (and, insultingly, cash). Violetta, already gravely ill, takes to her bed, where both Germonts visit her to make amends just as she is dying.

The company fielded a cast that was surprisingly inconsistent; although the good news is that, in the last two acts, the wobbliness evident through much of the first act had vanished, giving way to more solid, well-phrased singing and less flighty portrayals.

Maria Natale, made up to look uncannily like Madonna, proved a flexible and often powerful soprano whose dark hues at the low end of her range and bright, strong top notes created an alternately puzzling and endearing portrait of Violetta. The puzzling part was in the opening party scene, where she tossed off Verdi’s virtuosic filigree without much apparent feeling and where lines that ought to be clearly articulated sounded soft-edged. Yet in her interaction with the elder Germont and throughout the finale, her singing was the picture of clarity.

Mackenzie Whitney‘s portrayal of Alfredo followed a similar trajectory, from flighty and detached to passionate. He has an appealing light tenor, closer to that of, say, Afredo Kraus than to Luciano Pavarotti, and once he settled into the role, he used it elegantly.

Joo Won Kang used his satisfyingly rounded baritone to fine effect in his dignified – and, in his rendering of “Di Provenza,” his big second act aria, affecting – portrayal of Giorgio Germont, Alfredo’s father.

There was some fine singing in the smaller roles, too, most notably from bass Hidenori Inoue, as Baron Duphol. Kelsey Harrison and Russell Hewey, from the Portland Ballet, contributed a pas de deux in the third act party scene, and if the choral singing was generally tepid, the orchestra, conducted by Stephen Lord, sounded wonderful throughout.

Allan Kozinn is a former music critic and culture writer for The New York Times who lives in Portland. He can be contacted at:

allankozinn@gmail.com

Twitter: kozinn

Send questions/comments to the editors.