A LePage administration proposal that would require drug treatment providers and other professionals to report pregnant women suspected of substance abuse is receiving stiff pushback from medical organizations, women’s advocates and civil liberties groups.

Current law requires a host of professionals – from doctors and dentists to teachers, camp counselors and bus drivers – to notify the Maine Department of Health and Human Services whenever they know or suspect an infant was “born affected by illegal substance abuse” or needs medical attention because of prenatal exposure to illegal or legal substances, including alcohol.

The controversial proposal from Gov. Paul LePage would expand Maine’s child abuse “mandatory reporting” law to include incidents when observers believe a fetus “has been or will be affected by substance abuse” by the mother. The bill, L.D. 1556, also would add substance abuse treatment providers to the list of “mandated reporters,” a scenario that critics said could discourage drug-addicted women from seeking treatment.

“A woman might be afraid to seek help for fear of losing custody of their newborn child or of facing prosecution,” Malory Shaughnessy, executive director of the Maine Alliance for Addiction and Mental Health Services, testified last week to the Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee. “They may try detoxing on their own. Or they just may not seek services at all, including prenatal care.”

Physicians warn that trying to detox from an opioid addiction during pregnancy is dangerous to the unborn child, and that medication-assisted treatment is best for the fetus.

The proposal is one of dozens of submitted bills aimed at addressing – whether through treatment, law enforcement or “tough-love” measures – the opioid epidemic sweeping Maine. In 2016, the state saw a record 376 overdose deaths, or more than one per day. The majority of those deaths involved heroin, fentanyl or prescription opioids.

Fifteen states require health care workers to report suspected drug abuse during pregnancy, and three states – Alabama, South Carolina and Tennessee – have made drug abuse during pregnancy a crime, according to a 2015 report by the investigative journalism organization ProPublica.

LePage senior policy adviser David Sorensen told Health and Human Services Committee members that the governor’s bill is an attempt to address Maine’s soaring rates of drug-addicted newborns. It would allow the state to intervene and get women into treatment, he said.

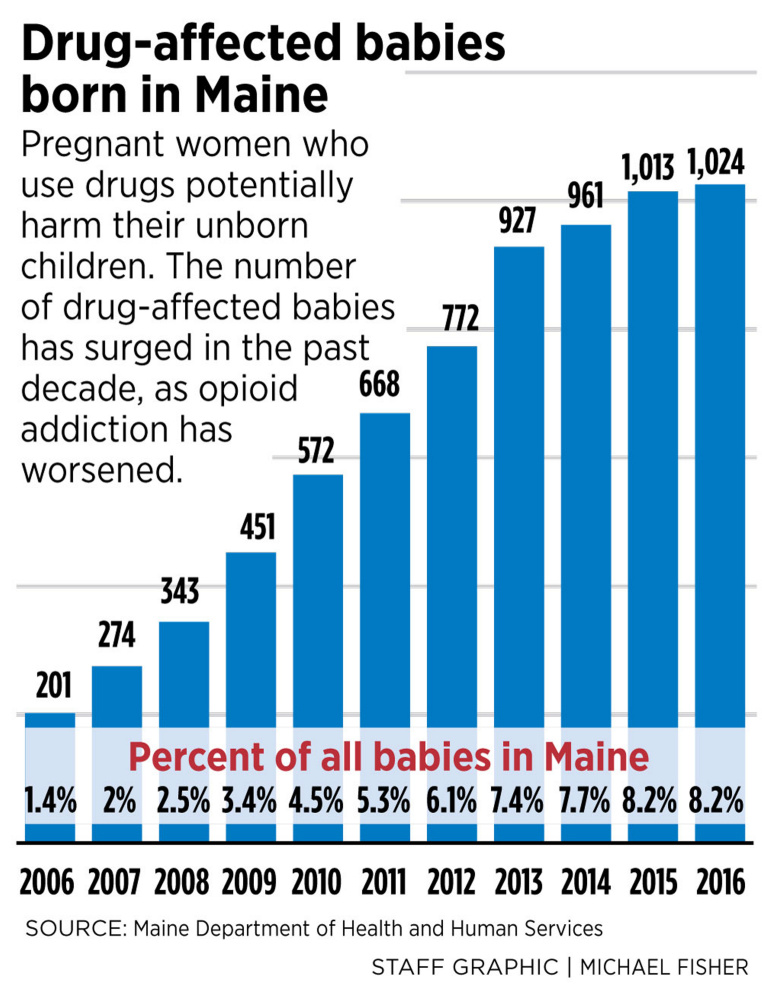

In 2006, 1.4 percent of the roughly 14,000 babies born in Maine were “drug-affected.” That percentage has ticked upward every year since, to the point where 8.2 percent of babies born in Maine last year – 1 in 12 – were drug-affected and were treated for withdrawal as newborns, according to statistics provided by Sorensen. The number of drug-affected babies in Maine grew from 201 in 2006 to 1,024 in 2016, according to the state.

Sorensen said expanding the mandatory reporting requirement would allow DHHS to “intervene on behalf of the mother and the child.”

“These changes would expand DHHS’ ability to identify families affected by this terrible trend and intervene on behalf of the mother and the child,” Sorensen said. “The sooner DHHS can get involved, the better the chances that the effects of drug exposure during pregnancy can be mitigated or prevented.”

But strong opposition from the medical and drug treatment communities likely means the bill faces difficult odds in the Legislature, particularly the Democrat-controlled House.

“Physicians are deeply concerned that this bill, if enacted, would scare pregnant women away from badly needed prenatal care due to the fear of being reported at the time of such care,” said Peter Michaud of the Maine Medical Association. Michaud testified that prenatal care is particularly important for pregnant women using drugs, allowing them to receive medication-assisted treatment and close monitoring.

“Withdrawal during pregnancy causes dangerous physical stress to the fetus,” Michaud said, according to written testimony. “Anything that would interfere with prenatal treatment, such as the prenatal reporting requirement in this bill, creates a serious risk of harm.”

Kate Brogan, vice president of public affairs at Maine Family Planning, dubbed the bill a “wrongheaded approach that continues to demonize vulnerable women and their children.”

Danna Hayes, director of public policy for the Maine Women’s Lobby, said the bill may be aimed at opioid addiction but it also includes abuse of legal substances, which could be a matter of opinion.

“For example, some women choose to occasionally drink alcohol while pregnant – and many doctors agree that an occasional drink is not unsafe. How would

mandated reporters determine how often a drink counts as alcohol abuse?” she asked.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Maine said the bill “is based on faulty assumptions and will unnecessarily insert the government into Mainers’ lives. … This legislation opens the door for reporting on all types of things that might harm a fetus, like not exercising, working long hours or being unable to afford regular prenatal care.”

In a 2011 opinion, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said that “legally mandated testing and reporting puts the therapeutic relationship between the obstetrician-gynecologist and the patient at risk, potentially placing the physician in an adversarial relationship with the patient.”

But LePage spokesman Peter Steele disputed the criticism of a bill that the administration views as a way to address that roughly one in every 12 babies born in Maine is considered drug-affected.

“Mandated reporting for pregnant women abusing substances wouldn’t discourage care any more than it does already for new mothers with drug-affected babies going to doctors’ offices,” Steele said when asked for comment.

The Health and Human Services Committee is scheduled to hold a work session on the bill Monday.

Correction: This story was updated at 12:12 p.m. on May 15 to correct the spelling of Danna Hayes’ name.

Send questions/comments to the editors.