Oscar Cronk is well acquainted with the sights, sounds, tastes and even smells of Maine’s wildlife. The 86-year-old is a longtime hunter and trapper who makes and sells bait out of his store in Wiscasset, using ingredients such as herbal oils and deer urine. He also makes regular trips to a camp in northern Maine.

So last week, when Cronk was watching a short presentation of archival hunting photos at the Maine State Museum in Augusta, he didn’t hesitate to correct the record when the big, antlered animals in one photo were identified as caribou.

“That’s moose,” Cronk said.

Bernard Fishman, the museum’s director, readily admitted his mistake and noted that he is neither a Maine native nor an experienced outdoorsman.

“I’m just a student,” said Fishman, who is preparing to deliver a longer presentation of the photos Saturday, as part of a multimedia project about Maine’s sporting history. “I have to be careful. I need to go through all this before I do this (presentation), so I don’t embarrass myself.”

Fishman may not have spent many nights on the forest floor or in the company of big game, live or dead, but his understanding of an old photographic technology has allowed the museum and several partner organizations to bring new life to a significant chapter of Maine history: that of the hunters, trappers, fishermen and other outdoors enthusiasts who have shaped the state’s wilderness and culture.

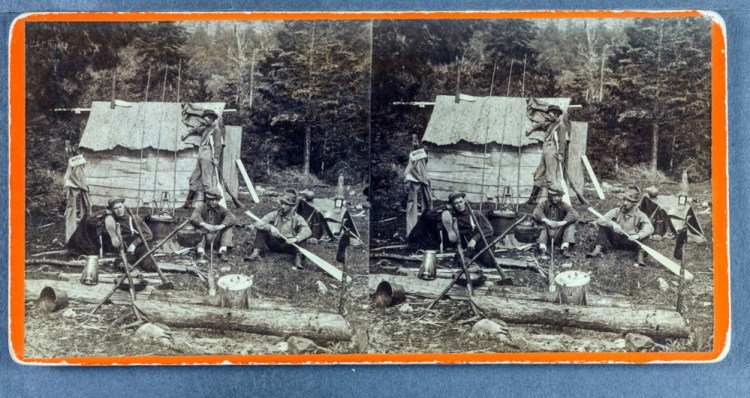

On Saturday, Fishman will present more than 50 photos at the Elks Lodge in Augusta. Those photos were taken between the 1860s and 1890s in a format known as stereoview, which allowed them to be viewed in three dimensions using special devices.

Many of those photos have never been seen by the public, Fishman said, and he has managed to digitize them so they can be viewed on a large screen. They depict everything from hunters in northern Maine camps to the moose, deer, wolves and other animals that have been hunted in Maine and around the Northeast. Fishman will distribute cardboard glasses with red-and-blue lenses that can be used to view the photos in 3D.

The organizers of the multimedia project include Friends of the Maine State Museum and the Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine. To complement Fishman’s photo presentation, they have also put together a 17-minute video documentary that features several Maine men and women, including Cronk, talking about going up to camp – or “uptah camp,” as the organizers have called it.

“It’s the first oral history project the museum has done,” said Jennifer Dube, development director of Friends of the Maine State Museum, a nonprofit group that supports the museum’s work. “By sharing oral histories and spending time with these communities, what we’ve done is really identify blind spots in our natural sciences program. We have bear and coyote (stuffed and on display in the museum). Now we can tell more meaningful stories about that bear and that coyote in the future.”

The project was partly funded with grants from the National Rifle Association Teach Freedom Foundation and the Maine Arts Commission.

Another hunter whose perspective is included in the documentary is Paul Wade, a veterinarian who runs the Cat Hospital in Manchester and who has donated numerous taxidermied animals to the museum.

“You’ve got to get up there all by yourself,” Wade says in the video of going up to camp. “You can’t have a crowd. You can’t have noise. I mean, I’ve had mice run up my legs. I have had a flying squirrel come down and land right next to me. I’ve had deer come up and just about take my hat off with their nose in my ear.”

Also interviewed in the video is Judy Sirois, a New York native who moved to northern Maine and has nursed animals such as coyote and bear in her home. Like Wade, Sirois speaks of the sense of solitude she has found in the woods, particularly at night.

“There’s no light, so the sky is brighter and the stars are brighter,” she says. “I’ve kayaked in the night around 10 o’clock. I was going around the corner, and I came across billions of fireflies, all lit up in one spot, and I think they were mating. I think that’s why they were all gathered there. I never had a camera to take a picture of that. It was just amazing.”

The video of those interviews will eventually be available on the museum’s website, and transcripts will be housed in its collections, according to Dube.

“It’s capturing a tradition and a knowledge before it’s long gone,” she said. “It’s a Maine community, and if we didn’t catch some of it now, we could lose it.”

Last week, Wade, Cronk and another hunter featured in the documentary, Robert Shelton, visited the museum to watch a short preview and to see a sampling of the photos Fishman will present.

They said they hope the project will convey the important role hunters have played in protecting Maine’s wilderness and managing the state’s wildlife populations. They also spoke of changes that have made hunting safer – like blaze orange clothing – and the need to draw younger Mainers away from their smartphones and into the woods.

They and the other people featured in the documentary will be at the event Saturday, which will go from 5 to 8:30 p.m. and include a buffet dinner and a discussion of the state’s sporting history. Admission is $60 and tickets can be purchased at mainestatemuseum.org and by calling the Friends of the Maine State Museum at 287-2304. All proceeds will benefit the project and museum programming.

Shelton, 78, grew up in Augusta and eventually became a surgeon. He recalled hunting trips to the Allagash. He described killing his first deer at the age of 12, and killing the largest deer of his life in the 1980s on a winter day when the temperature was minus 20 degrees. Surgery is supposed to be one of the most stressful careers, Shelton said, and he has always found the outdoors to be a good antidote.

“There can’t be a bigger high in a bottle or a needle or a pill than seeing a 10-point buck with the sun shining off his rack walking up on you,” he said. “There’s no bigger thrill in the world than something like that.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.