One of the now-retired Portland police detectives who investigated the 1989 murder of Jessica L. Briggs has turned over two boxes of case files he has kept in his attic, including material never before disclosed to Anthony Sanborn Jr.’s defense team, court documents show.

Portland police Detective James Daniels, the lead investigator in Briggs’ murder, returned the boxes to the Portland Police Department on April 26, after they were stored for an unknown amount of time in his attic, according to court documents filed Monday by Sanborn’s attorney, Amy Fairfield. She used the filing to reiterate her request for a judge to set aside Sanborn’s conviction.

Sanborn was sentenced to 70 years in prison for the murder in 1992 and had been in jail until he was freed on bail April 13, when a judge determined that he was likely to prevail in his effort for post-conviction review.

In the new court filing, Fairfield wrote that she found original witness statements, original police reports, photographs of alternative suspects, and what appeared to be physical evidence, including a knife and a box cutter. Fairfield also asserts that handwritten investigative notes turned over by Daniels’ partner, Daniel Young, show that Daniels lied on the witness stand at Sanborn’s 1992 trial about who was shown photo lineups during early moments in the investigation.

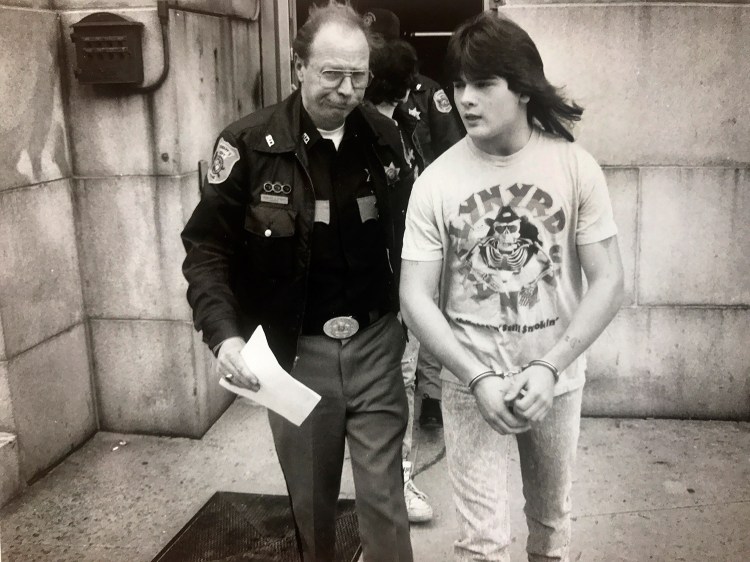

Anthony Sanborn Jr., shown in a handout photo from April 1990, was convicted of murdering Jessica Briggs and sentenced to 70 years.

“There was … evidence and information in those boxes that was exculpatory and absolutely and unequivocally should have been turned over to the defense,” Fairfield said in a telephone interview Monday. “There is conclusive proof of some really bad behavior on the part of the state actors who handled this case. I had it before. I just have a lot more of it now.”

This most recent filing adds to Fairfield’s argument that police and prosecutors colluded to hide evidence from the defense nearly 30 years ago and coerce witnesses to testify against Sanborn, who has proclaimed his innocence since he was charged with Briggs’ murder in 1990.

According to court records and media accounts at the time, the murder investigation began on a drizzly morning in May 1989, when police were called to the Maine State Pier, which at that time was partially occupied by a Bath Iron Works dry-dock.

Near a dumpster at the end of the pier behind the BIW receiving department, police found a pair of black high-heeled shoes, a woman’s earring, a pack of cigarettes and a fresh pool of human blood. Drag marks pointed to an opening that led to the water. When divers pulled Briggs’ body from Casco Bay, they found her throat had been cut, and she was stabbed multiple times and nearly disemboweled.

During the trial, workers from BIW testified about seeing a woman who was apparently Briggs walk across Commercial Street headed toward the pier around midnight, pushing a bicycle with a young man at her side.

BIW’s second shift had just let out, and a charter bus was idling near the entrance to the pier to take workers back to the Bath area, documents from the trial say. Police interviewed and turned over information about three interviews with workers who were on the bus that night.

But Fairfield alleges that notes provided by Young show they interviewed at least 11 people. One of them was John Asquini, the bus driver, who saw a third person walking ahead of Briggs and her companion.

Based on an eyewitness account in 1989, police prepared this sketch of a man seen walking near Jessica L. Briggs and another man before she was murdered. It had been stored with case materials turned over to Anthony Sanborn Jr.’s attorney last week.

Asquini worked with a police sketch artist to develop a composite of the man, but the sketch was never turned over to the defense at trial, and had never been seen by Sanborn’s attorneys until Fairfield viewed it April 28, she wrote in the latest filing.

Fairfield said she has been looking for that composite sketch ever since she took on Sanborn’s appeal in 2016. “I think that could be the end-all, be-all,” she said.

A story published June 1, 1989, in the Evening Express newspaper described how police had prepared a sketch of someone seen on the pier with Briggs that night, but they did not release it or indicate whether they believe the person in the sketch was the man who killed her. It is also not clear whether the sketch provided in court documents this week is the same sketch described in the Evening Express story.

Also described in the new filings is a segment of video footage that was altered and edited before it was disclosed to the defense, Fairfield said.

In the filing, Fairfield describes how a roughly 10-minute segment was prepared by a news crew at WCSH-TV shortly after Briggs was killed. The segment had six parts. But the copy of the footage turned over to the defense in the case was reproduced without audio and omitted the final part.

The original and unedited news reel has been turned over to Fairfield, she wrote, and the sixth deleted scene showed Portland police detective Young interviewing BIW employees on the bus back to Bath.

At trial, Daniels said he did not show any photo lineups to people on the pier because they all said they could not identify anybody. But the handwritten notes by Young appear to contradict this testimony directly.

At the top of one page, Young wrote “Photo Series #2,” with a list of names of potential witnesses, and their reactions to viewing a lineup. Later on in the notes, a page is titled “Line-up as shown,” with six entries; two are names, including “Ingalls,” another witness and a friend of Briggs interviewed by police at the time. The other four entries are all five-digit numbers.

Fairfield also reiterates allegations that she can prove that police had more extensive knowledge of accusations of rape against a key witness who testified against Sanborn.

Gerard Rossi was in his 30s when Briggs was killed, and was a close friend and roommate of Sanborn. At trial, Rossi testified that after the killing, Sanborn confessed to her murder on three occasions.

Jessica L. Briggs, the murder victim

But Fairfield alleges that police had received information that multiple underage girls had reported that Rossi drugged and raped them, including Michelle Lincoln, a friend of Sanborn’s at the time of the murder who later married him in 2012.

Both Daniels and then-Assistant Attorney General Pamela Ames, now an attorney in private practice in Waterville, did not return a call for comment Monday. A phone number for Young could not be located.

A spokesman for Attorney General Janet Mills said her office had no intention of litigating the case in the media. “We will present our position on the issues to the court at the appropriate time,” Timothy Feeley said.

In written affidavits submitted in April, both Daniels and Young denied allegations of coercion and hiding evidence.

“The reports I completed in this case are truthful (and) factual,” Young said in the affidavit. “There were no ‘secret deals’ or suppressed interviews in this case. Det. Daniels and I, along with the prosecutors, have professional standards and moral beliefs that were followed throughout this investigation.”

The storage of original police documents and investigative materials at a detective’s home raises new questions about police policy and practices at the time of the investigation.

Michael Chitwood, who served as Portland police chief during the time of the murder and trial and is now police superintendent in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, did not return a call for comment.

Chitwood previously has defended the work of his detectives on the Briggs homicide, along with the professional standing of Ames, Young and Daniels, saying that all are “three superb and ethical people.”

Typically, from the first moment when a piece of evidence is identified at a murder scene, investigators and evidence technicians create extensive records that are known as chain of custody documentation describing who controlled the evidence, said Joseph Latta, executive director of the International Association for Property and Evidence, a nonprofit group of property room professionals.

Latta, who is not connected with the Sanborn case, said that in general, standard police procedures should spell out how the evidence must be handled and stored, who must approve of its transfer from one person to another, and when – if ever – the evidence may be destroyed.

These policies are designed to lower the risk of inadvertent contamination or intentional meddling, and help preserve the integrity of evidence when it is presented at trial, Latta said.

He said he could not think of any reason for a detective to keep original copies or physical evidence at his home.

“Standards would always say it should be kept under lock and key at all times,” Latta said. “As a defense attorney, I’m going to jump on that. The chain of custody has sort of been broken.”

Portland police provided to the Portland Press Herald a copy of their evidence control procedures circa 1993, the earliest such policy that was readily available. It does not directly address evidence removed from the property room by detectives or other department personnel.

A revision in the policy dated 2013 adds a pertinent section, “Preservation of Chain of Custody,” which requires all persons who temporarily remove material from the property office to record basic information, such as what they are removing, the date they are taking it, the reason for the release, and the date of return.

A call to Portland Police Chief Michael Sauschuck, was not returned Monday.

Beyond the issue of evidence handling, Fairfield has alleged in multiple court filings that police and prosecutors colluded to withhold information helpful to Sanborn.

At the April 13 hearing, the star witness in Sanborn’s trial, Hope Cady, recanted her testimony entirely.

Cady had testified in 1992 that she saw Sanborn stab Briggs from a distance on a dimly lit pier sometime around midnight. But Cady had serious vision problems that were uncorrected at the time of the murder, a fact that was never disclosed to the defense, Fairfield said.

Matt Byrne can be contacted at 791-6303 or at:

Send questions/comments to the editors.