When President Trump and the Republican majorities in Congress swept away privacy rules preventing your internet service providers from selling your data without your permission, you might think Fletcher Kittredge would want to celebrate.

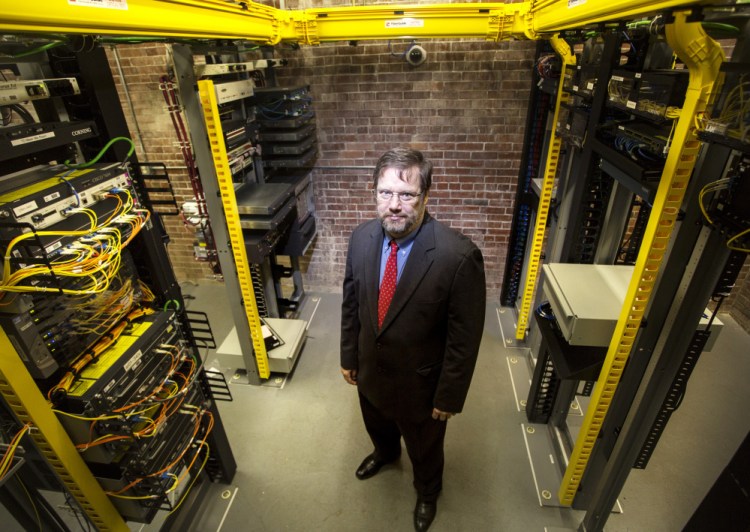

Kittredge, after all, is founder and CEO of Biddeford-based GWI, an internet service provider that serves more than 18,000 Maine customers and would benefit from the repeal, which lets companies like his sell his customer’s Web browsing history, geo-location movements, and all sorts of other valuable information to advertisers. The rules, repeal advocates said, had put more stringent restrictions on such firms than are applied to Web-based companies like Facebook or Google.

But Kittredge says the repeal is a disaster for his customers and anyone who cares about privacy or civil liberties, an ill-conceived move that will ultimately make people’s data less secure and the internet itself less valuable.

“ISPs have broader access to information about you than anybody else because everything else goes on top of the connection they provide,” he says. “They can tell who you’re having conversations with, where you go, and lots of information that’s best left private, especially as hackers will be attracted to it.

“If we all end up not being able to appropriately trust the internet, that’s not good for anyone.”

The rule repeal – which the president signed into law April 3 – will make most things we do on the internet much less private, privacy experts say, as providers learn how to make money selling their customers’ data. For years prior to the repeal, providers had been expecting tightened rules and had set their policies to anticipate this, but now are free to exploit data more aggressively. This has implications for Maine internet users and national policymakers alike.

Proponents of the repeal said it was necessary to create an even playing field between internet service providers and other Web-based companies, but the practical effect so far has been to shift the balance in favor of service providers, who can now operate with far fewer privacy restrictions.

“There are no rules here now,” says lawyer Peter Guffin, who heads Pierce Atwood’s privacy and data security practice and teaches information privacy law at the University of Maine School of Law. “There’s a complete vacuum in terms of when an ISP can see into the contents of our communications, what it can do with those contents, and even whether it has to tell us if this data has been hacked.

“From a user’s perspective, you should be on notice that the ISPs have been given the green light by the U.S. government to essentially surveil all of your electronic communications,” Guffin added. “My hunch is that many providers are rewriting their privacy notices, and whatever they said about opting out won’t be the same as a year ago.”

Internet providers can see a wide range of their customers’ online activity, according to Jeremy Gillula, senior staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the San Francisco-based digital civil liberties group. Unless you’re using special tools like a virtual private network or the free, privacy-minded Tor internet browser, he says, “an ISP could definitely see and sell all the web addresses you visit,” though they would be limited to the domain name for “https” sites using encryption, such as banks, most online shopping sites, Google, Facebook, and Web mail.

They can also gather your geo-location data – especially interesting for mobile internet – and could glean what songs you’ve been listening to, movies you’ve watched, or items you’ve shopped for from any unencrypted addresses you’ve visited.

While they can also see the content of emails in accounts they provide their users, wiretapping laws likely prevent them from sharing or selling this information.

Reducing exposure to snooping

There are steps Mainers can take to reduce their exposure, says Zachary Heiden, legal director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Maine. One is to use the Tor browser (download the Tor browser here) – though it will slow down your internet traffic – and encrypted text messaging tools like Signal (download Signal here).

“That will at least protect the content of your communications,” he says. “But it doesn’t protect the metadata” – the digital equivalent of a letter’s envelope, with sender, receiver, time stamp, and size information about the text.

Users can also ask their ISPs to opt them out of at least some of their data being shared, though this process is often cumbersome. “An ACLU colleague of mine who is an expert on internet privacy tried as an exercise to contact different ISPs and exercise the opt-out option and found it incredibly challenging and confusing – and this is somebody who studies technology for a living,” he says. “But if you care about privacy and don’t want your personal browsing history stored, commodified, and sold then it may be worth it for you to take those steps to opt out.”

More sophisticated users may consider subscribing to a virtual private networking – or VPN – service, which masks much of one’s internet activity from your service provider, but experts say that comes with its own risks, as the VPN provider may be snooping on you itself.

“There’s a strong overlap between VPN companies and the dark web, because a lot of people who want to hide things this way are also doing something wrong,” says Kittredge. “It can be like hiring a security guard to protect your warehouse by going to the local bar and picking out somebody who looks tough.”

A fourth possibility, depending on your geographic location: “Vote with your wallets and choose ISPs that are protective of your privacy,” Heiden says.

Most ISPs active in Maine are seeking to reassure customers about their commitment to their privacy, but on closer scrutiny, the strength of their stated commitments varies considerably.

Another unknown is what lawmakers will do next.

Repeal’s goal: An ‘even playing field’

Congress repealed the privacy rules the Federal Communications Commission was about to put into effect that would have prohibited internet providers from selling or sharing a wide range of personal data without users’ consent, including Web browsing history, geo-location, and application usage. It was a party-line vote, with Sen. Susan Collins and Rep. Bruce Poliquin voting with their Republican colleagues for repeal, independent Sen. Angus King, Democratic Rep. Chellie Pingree and the entire Democratic caucus voting against.

The action also prevents the FCC – the only entity currently authorized to regulate ISPs – from developing new rules.

Supporters of repeal say it was necessary to create an even playing field between ISPs and other internet firms like Google and Facebook. The FCC rules on internet providers were stricter than those for Web-based firms and application developers, which are regulated by a different agency, the Federal Trade Commission. Opponents reject this as a false comparison.

Poliquin says that repealing the rule will enhance privacy. “I absolutely want to ensure there are proper safeguards to keep Mainers’ private data secure when they use the Internet, which is why I voted with Senator Collins to remove this FCC rule,” he said in a written statement to the Maine Sunday Telegram. “The reality is that the FCC rule creates a misleading sense of security for users” because they applied “to only a specific segment of the industry, while giving unequal advantage and preference to a handful of companies that wouldn’t be under their jurisdiction. This is not the way to regulate, as it would also undermine the very goal of protecting users’ data.”

His vote, he added, was “the right thing to do.”

According to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics, internet firms have not been important campaign donors to either Collins or Poliquin. No member of the industry appears in the top 20 donors to either’s campaign or the political action committees they control.

Users don’t pay Google, Facebook

The most prominent advocate pushing for the changes is Jon Leibowitz, a former movie industry lobbyist who was chairman of the Federal Trade Commission under President Obama, and is now co-chairman of the 21st Century Privacy Coalition, which represents and lobbies on behalf of Comcast, Time Warner Cable (now Spectrum), Verizon, DirecTV and other major internet providers who disliked the restrictions.

In interviews with the Telegram, Leibowitz defended the rule change on fairness grounds. “The whole history of American privacy protection is focused on three things: the data itself, the way in which it’s collected, and the way in which it’s used,” he said. “You shouldn’t discriminate on the basis of silos, on the basis of who is doing the collecting.”

ISPs, he and other proponents of the repeal argue, should be on an even playing field with other internet firms in terms of exploiting users’ digital data. But repeatedly asked why internet service providers should necessarily operate under the same rules as Web companies, he was unable to provide a clear answer. “It’s not about who is collecting your data, it’s about what data is being collected and how it is being used,” he reiterated, adding that he thought you could make a fair “apples to apples” comparison between ISPs and other internet firms.

Elsewhere he has argued that ISPs don’t really have a comprehensive picture of our internet use, both because they can’t see the content of browsing at “https” sites and because customers roam from ISP to ISP during the day, connecting at work or the local coffee shop.

Opponents of the rule change disagree, arguing there is a fundamental difference between the companies we pay to provide us internet access and those like Google and Facebook that are paid by advertisers for information about who we are and what products we might like. For internet service providers, they say, their users are their customers, while for Google and Facebook their users are the product they’re selling to their real customers, marketers and advertisers.

“It’s a little disingenuous for ISPs to argue they should be treated equally, because it’s not really comparing apples to apples,” Pierce Atwood’s Guffin says. “Unlike using Google, which is free, I’m actually paying my ISP 50 bucks a month to get that ISP connection, and now I find out all my data is also being monetized and leveraged to make more money.”

ISPs, he says, are more akin to the postal service – a conduit through which we conduct our digital lives, and one you can’t avoid having, which is why European regulations prohibit such firms from collecting user data. Nor do most Maine consumers have a lot of options, as many communities are served by just one or two providers. “It’s an essential service, and there aren’t hundreds of ISPs that are knocking at my door for business,” he adds.

Heiden at the ACLU of Maine agrees. “The rules should be different, because ISPs are literally invited into our home and provide a service that is almost necessary for participating in the public and economic life of our country,” he says. “That carries with it a social responsibility that’s different than that of the Web companies we may choose to visit through the internet.”

It’s unclear how or when privacy rules will be replaced

In the short term, the repeal has also created a profoundly uneven playing field, as ISPs are now far less regulated than other firms. It is unclear how and when Congress will move to rectify the situation, given that the FCC still has authority over the ISPs yet is barred from developing privacy regulations.

Some backers of the repeal appear concerned about the vacuum. On April 7, 50 Republican House members wrote the FCC chairman to urge him “to continue to hold ISPs to their privacy promises” laid out in the privacy policies they present their users. The letter also suggested the FCC should turn regulation of ISPs over to the FTC. (Poliquin was not a signatory.)

But Gillula of the Electronic Frontier Foundation says that’s not reassuring, as many major ISPs’ privacy policies allow them to collect your browsing history and target ads at you unless you opt out, something most users are unaware they can do. “Basically, the letter is kind of like asking the FCC to ensure that the fox guarding the henhouse stands by the contract he imposed on the hens, which says in fine print that he’s allowed to eat one or two of them now and then,” he says.

It’s also possible that the Maine Legislature could try to impose its own rules, though this might be tested in court. “This is all uncharted waters,” says Guffin. “But if you have Congress saying we’re not regulating ISPs, it may create an opening for states to step in.”

Colin Woodard can be contacted at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Clarification: This story was revised at 12:50 p.m., April 24, 2017, to clarify that former FTC chairman Jon Leibowitz is a former lobbyist who co-chairs an organization that represents and hires lobbyists on behalf of large broadband companies.

Send questions/comments to the editors.