Marsden Hartley claimed Maine as his own in 1902, when he visited Kezar Lake and Center Lovell on the state’s western edge for the first time. It felt distant from the busy mills of Lewiston, where he was born 25 years earlier and where he grew up, and a world removed from New York, where Hartley had begun showing the promise of his art education.

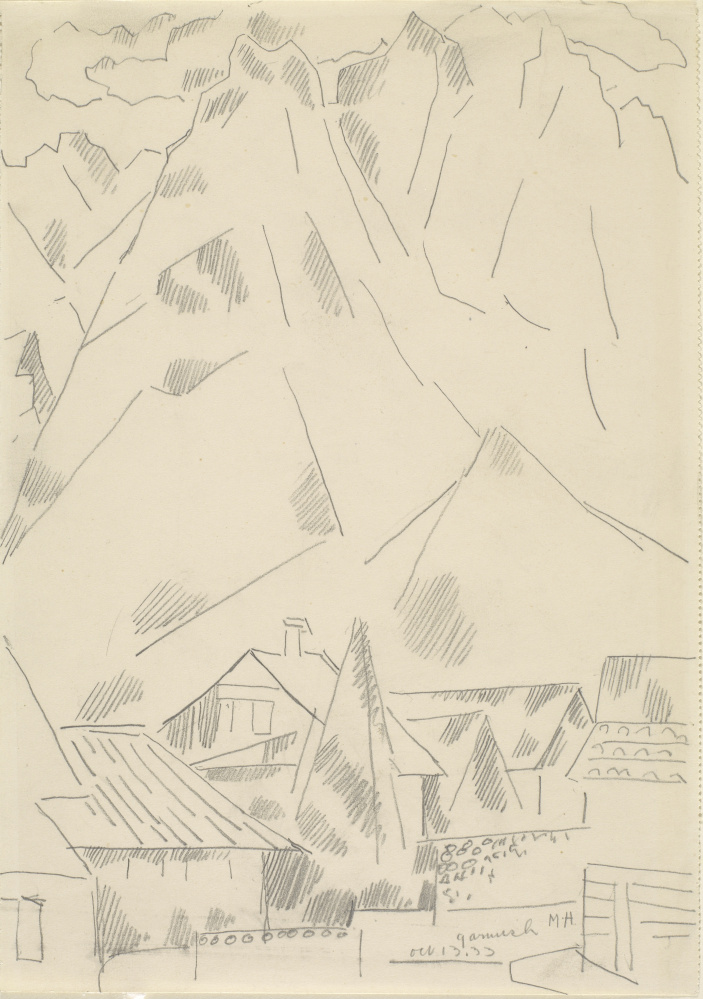

He spent three summers at Center Lovell, from 1902 to 1904, living for a time in a cabin at Hewnoaks, then a seasonal art community and now the home of an artist residency program. “The moon is shining so perfectly bright,” he wrote to a friend, “and the mountains stand out in somber grayness.”

Hartley left Maine soon after, returning only occasionally until he came home for good late in his life. But wherever he went – New York, Paris, Berlin – he brought the somber gray mountains of Maine with him. “His letters are filled with comments about Maine. He doesn’t forget it,” said Donna M. Cassidy, who teaches art history and New England studies at the University of Southern Maine. “No matter where he was, the hills of Maine always followed him. They were part of his life and part of his way of thinking.”

Cassidy is co-curator of a new exhibition, “Marsden Hartley’s Maine,” on view through June 18 at the Met Breuer, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s modern and contemporary art space in Manhattan. The exhibition moves to Colby College in Waterville on July 8.

Other museums in Maine are taking advantage of the interest in Hartley. The Portland Museum of Art is showing a half-dozen Hartleys, the Ogunquit Museum of American Art will show at least one when it opens for the season May 1, and on June 9 the Bates College Museum of Art opens “At Home and Abroad: Works from the Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection,” a companion exhibition to the New York and Waterville shows. It begins with his childhood in Lewiston and includes the time he spent in Europe, including his visits to Germany and France where he learned from artists, artistic movements and expatriates.

In addition, the Maine Office of Tourism has a link on its website directing people to “The Art of Marsden Hartley,” including museums in Maine that are showing his work this year and places in Maine where he painted.

“On the Banks of the Androscoggin River at Lewiston, Maine, My Birth Place,” ca. 1911, from “A Portrait History of Marsden Hartley,” photographer unknown, from “At Home and Abroad” at Bates.

Hartley had a sad childhood in Lewiston. His mother died when he was 8, and his father struggled to maintain a job in the mills. The family eventually resettled in Ohio, where Hartley took his first painting lessons. He came back to Maine in 1900 at age 23 and stayed here, either living year-round or parts of the year, through 1911. After that, he left for Europe and returned to Maine only occasionally until he came back for good in 1937.

He died in 1943 in Ellsworth, after spending the last years of his life in the Downeast fishing village of Corea.

“Marsden Hartley’s Maine” exclusively features paintings that Hartley made in Maine or paintings of Maine that he made elsewhere. It’s the first major exhibition that looks closely at his relationship with Maine, revealing Hartley as a modernist painter with an abiding love of landscape and one who was deeply and spiritually tied to his place of birth, even if he spent much of his life trying to distance himself from it. He had a love-hate relationship with Maine, deriding its provincialism and probably never quite feeling at ease as a gay man, knowing he would never be accepted here as he was in Berlin. But he recognized the state’s influence on his art and proudly claimed it as his own when he came back late in his life.

“He loved Maine and he loved the landscape, but he complained about a sense of isolation from intellectual hubs,” Cassidy said. “Early on, he was always going back and forth to New York and Boston, from Lewiston and Lovell, and later, from Corea to New York. He really felt, as many artists do, that sense of needing to be connected to these artistic hubs but also needing that time away.”

‘THE PAINTER OF MAINE’

The Maine exhibition won’t reshape how people view Hartley’s career. His best-known paintings will remain his Berlin paintings, which combined abstraction with German expressionism, said Elizabeth Finch, a curator of American art at Colby and co-curator of this exhibition with Cassidy and Randall R. Griffey of the Met. But this show reinforces the importance of Maine on Hartley’s life and work, his difficult personal history with the state and, ultimately, his pride in calling himself “the painter of Maine,” a distinction he felt he owned as the only native Mainer among the many modernists who came to the state in the early- to mid-20th century.

“The revelation of this show is the role that Maine played in his work throughout his career,” Finch said. “He found his subject here, carried it around with him and returned to it from memory when he was in New York, Paris and elsewhere.”

Below, “Intellectual Niece,” depicting Hartley’s niece Norma Berger, 1939-40, oil on academy board, 22 by 22 inches.

The New York exhibition has become a source of pride for those involved in the project from Maine. Colby originated the show, the impetus a gift of nearly a dozen Hartleys to the museum from the Alex Katz Foundation. “With one fell swoop, we had depth in Hartley,” said museum director Sharon Corwin. The museum showed the Hartleys in 2015, soon after receiving them, and began thinking about his work in Maine in the broader context of his life and career.

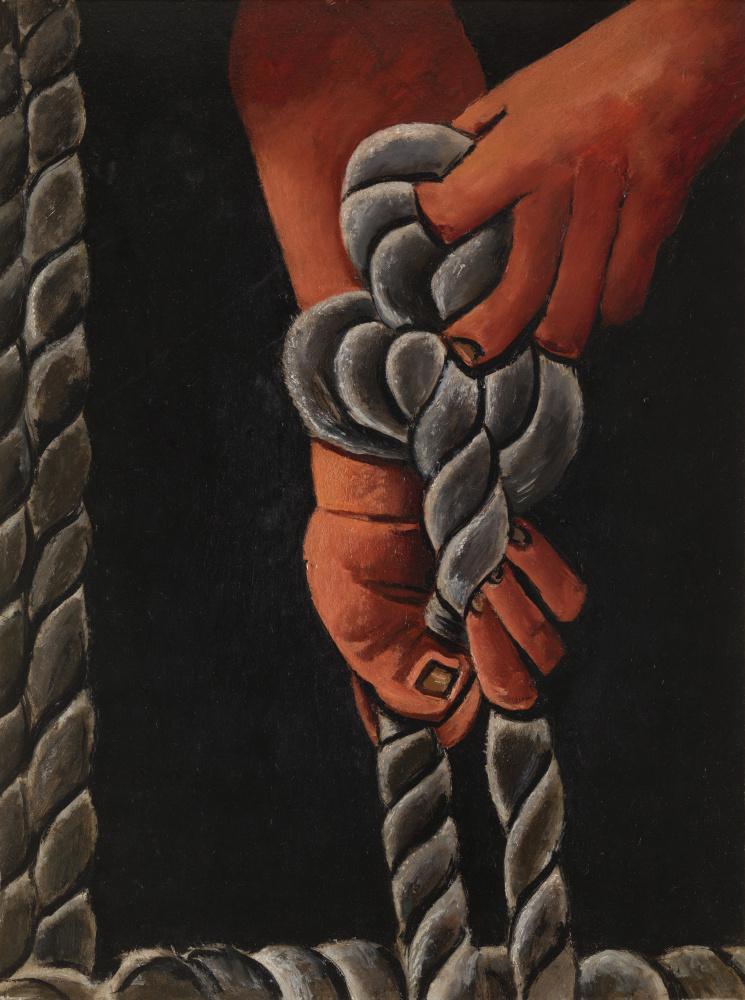

The Met was a logical partner. It also has a large holding of Hartley paintings and works on paper, acquiring its first Hartley, “Lobster Fishermen,” in 1942, the year before the artist died. A picture of six lobstermen gathered on the pier, their traps serving as places of rest, Hartley painted it in Corea.

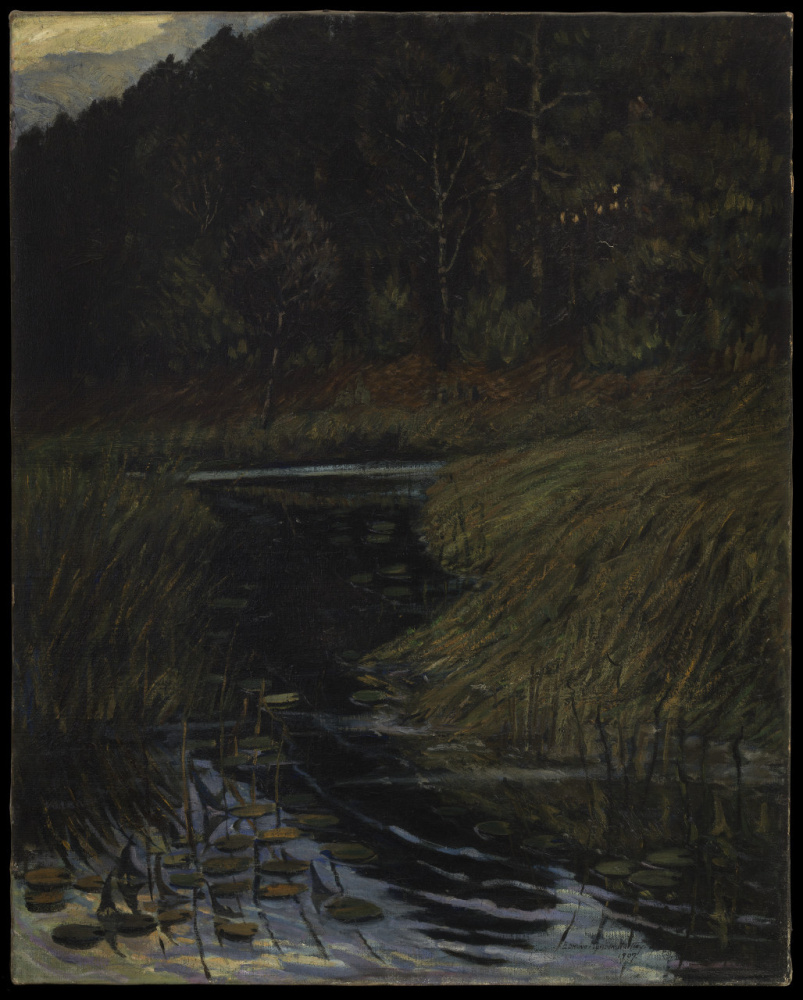

The curators borrowed from dozens of museums, including the Portland Museum of Art, the Ogunquit Museum of American Art and the Bates College Museum of Art. Among the other Maine donors was the Lewiston Public Library, which loaned its 1907 oil painting “Shady Brook” to the exhibition. It’s the earliest painting in the show and the first thing people see when they enter the exhibition at the Met Breuer. It is believed to be based on a scene from western Maine, very likely from around Center Lovell.

The painting is a dark rendering of a pastoral setting, with lilies and reeds reaching from lazy water in the foreground and giving way to a sweeping hill in the background. Hartley gave the painting to the library soon after he completed it. He had a studio nearby and presented the painting as a gesture of appreciation for the library and its services, Finch said.

Although a lot of people don’t like the painting – “It is very dark,” said library Director Rick Speer – it is a source of pride locally, especially now that it’s part of a New York art show that is generating national attention and positive reviews. The Lewiston library has loaned “Shady Brook” to the Portland and Bates museums, but it’s never been out of Maine until now.

Speer was surprised when he received a letter from the Met two years ago that extolled the importance of the painting and requesting permission to borrow it. Speer always liked the painting, but he had no idea how highly others thought of it. “They said some pretty amazing things about it,” he said.

The Met reframed the painting as part of its installation.

Speer attended the opening in New York and came away impressed by how well Hartley portrayed Maine and how well the curators portrayed Hartley. “It was just so heartwarming to see Hartley honored like that,” he said. “To see Maine featured, to see Lewiston featured and spoken of so highly was just really nice.”

He was especially impressed “by the big bold strokes and the brighter colors” of some of Hartley’s later Katahdin paintings. People from Lewiston who know Hartley only through “Shady Brook” will be surprised to see how his paintings evolved after he left town, Speer said.

William Low, curator at the Bates museum, also appreciated the visual impact of the New York exhibition.

“There have been a couple of significant Hartley exhibitions in the last 10 or 15 years, but no one has ever really taken a look at the Maine paintings,” he said. “He did some serious, significant work here, and it’s a real pleasure to see them all grouped together.”

People who look closely will see Hartley’s conflicted feelings for Maine throughout the exhibition. Some landscapes are brilliantly colorful and luminous, creating an upbeat sense of place and the carnival atmosphere of autumn. In other paintings, a belching cloak of darkness covers those same mountains. There’s no brilliance in the foliage. The trees and barren and the farms abandoned. It’s an image of Maine as an unwelcoming place.

“That was something he holds with him a long time,” Cassidy said. “He was hesitant to come back.”

But he did come back – as a successful artist. Hartley finally had money in the bank when he returned to Maine in 1937, a result of museums buying his paintings.

Low thinks the artist would appreciate the attention that’s being paid to his Maine roots.

“Ultimately, he was a very, very proud Mainer,” Low said. “He was always a proud Mainer, but it took him awhile to realize the depth of it.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.