The brutal killing of a 16-year-old Portland girl in 1989 was most likely the work of a serial killer and not the victim’s teenage boyfriend who was convicted of the slaying, a respected forensic profiler working for the man’s defense team has said.

New evidence uncovered by attorneys for Anthony Sanborn Jr., and first filed in Portland Unified Criminal Court last week, also has prompted the state Attorney General’s Office to request a bail hearing for Sanborn on Thursday. Sanborn has maintained his innocence since he was convicted of Jessica L. Briggs’ murder in 1992 and later sentenced to 70 years in prison.

Jessica L. Briggs, who dated Anthony Sanborn Jr. briefly, was 16 when she was killed in 1989.

At the hearing, Justice Joyce Wheeler is expected to hear testimony from Hope Cady, who was 13 years old and living on the streets of Portland when she claimed to have witnessed Sanborn kill Briggs from a distance at the end of a dimly lit pier late one night, said Amy Fairfield, Sanborn’s attorney.

Fairfield also has filed papers with the court indicating that a forensic profiler reviewed the case and will submit a written opinion describing how Briggs’ killing was likely premeditated by someone who had killed before, and did so out of a pathology that developed over time, and ruling out Sanborn as the possible killer.

The profiler, John Philpin, said in a phone interview Monday that Sanborn, at 16, was too young and too inexperienced to have killed Briggs, whose remains showed signs of deliberate brutality that exceeded the crime of passion described by prosecutors.

Philpin said many perpetrators of so-called one-off killings will snap to their senses the moment they see the damage they have inflicted on another human being.

“That’s not what happened here,” Philpin said. “It wasn’t a one-off kind of deal, ‘Oh my god, what have I done.’ There’s a much larger dimension – terrorizing, humiliating and destroying.”

Cady’s testimony Thursday could upend the state’s version of the case, which relied on Cady as its star witness. At trial, Cady said she was some distance away in a hidden location on an adjacent pier when she saw Sanborn encircle Briggs along with at least three other people before she said she saw Sanborn stab Briggs repeatedly.

New evidence uncovered by Fairfield, however, shows that Cady has had serious and well-documented vision problems since she was a child, and was most likely legally blind when she claimed to have witnessed the killing.

According to a doctor’s evaluation performed about 18 months after the killing and described in a 104-page motion for bail filed Wednesday, Cady’s vision was tested at 20/200, meaning her view of an object at 20 feet was comparable to a normal person’s vision of the same object at 200 feet.

TESTING CREDIBILITY OF TESTIMONY

The information about Cady’s history was disclosed to Fairfield last year after the Attorney General’s Office agreed to turn over an expansive volume of confidential records held by Cady’s state-appointed social worker that were never made available to Sanborn’s original attorneys, Neale Duffett and Ned Chester.

In a phone interview Monday, Fairfield lauded Assistant Attorney General Donald Macomber, who assisted Assistant Attorney General Pamela Ames in prosecuting Sanborn 25 years ago. Macomber is now representing the state in Sanborn’s current motion for bail.

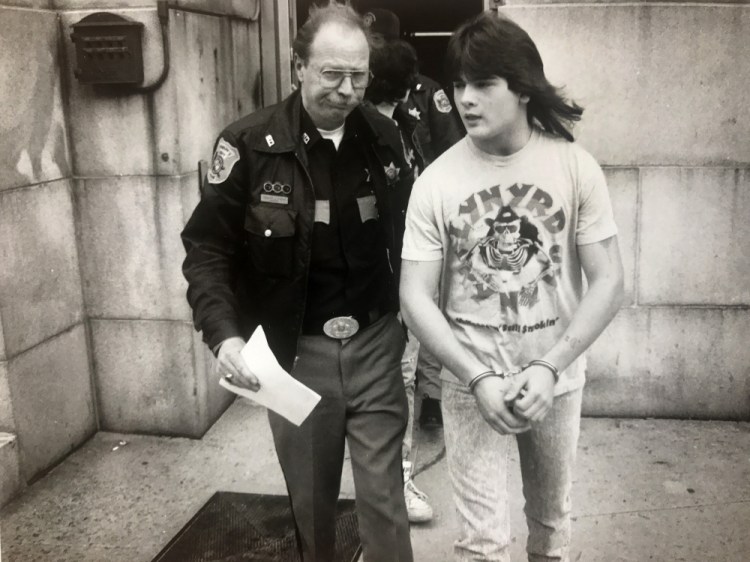

Anthony Sanborn Jr., right, looks toward the public seating area as the jury files out of court on Oct 27, 1992, during Sanborn’s murder trial. With him is Edwin P. Chester, one of his attorneys. Sanborn was convicted after a nine-day trial and sentenced to 70 years in prison.

“I think I raised some very troubling issues with the investigation and with then-Assistant Attorney General Pam Ames, and I think that Don is looking now to test the credibility of the testimony that put Tony in jail, and I think that is extremely commendable,” Fairfield said. “I couldn’t ask for a more gracious and honest and forthright prosecutor.”

Macomber did not return a call for comment, but a spokesman for the Attorney General’s Office confirmed that the state requested the bail hearing Monday.

Ames, who is now a private defense attorney in Waterville, has not responded to two requests for comment left with her office last week.

In addition to the suppressed evidence of Cady’s vision problems, Fairfield alleges in the bail motion that prosecutors and police colluded in multiple ways to prevent Sanborn’s defense attorneys from receiving information that would have undermined their case.

In addition to Ames, Fairfield’s allegations center on the two Portland police officers, lead investigator Detective James Daniels and Detective Daniel Young.

Normally, prosecutors are required to turn over their evidence to the defense in a process called discovery. This includes all material that would either help the accused or impeach the credibility of a state’s witness.

Fairfield documented multiple instances in which prosecutors knowingly withheld information, including a copy of a police report taken from the prosecutor’s files that includes a handwritten sticky note with a reminder that three witness statements should be withheld from the defense.

PROBE FOCUSED ON STREET KIDS

Both Sanborn and Briggs were 16 at the time of the murder, and belonged to a rough-and-tumble group of teenagers living on the streets of Portland, staying with friends or at shelters, doing drugs and drinking, and trying to avoid the police.

Police focused almost exclusively on the group of street kids who knew Briggs and Sanborn, despite not finding physical evidence at the crime scene linking Sanborn to the killing, and semen samples taken from Briggs’ body that were not from Sanborn.

This focus on the street kids, to the exclusion of other possible suspects, was an immediate red flag to Philpin, who also reviewed trial transcripts, investigation records and documents filed in the case.

At the time of Briggs’ murder, the Maine State Pier was partially occupied by a Bath Iron Works dry-dock. Naval ships docked regularly, with sailors staying aboard the ships or in nearby barracks.

Philpin said he found no records that indicate police checked the background of sailors who may have had shore leave that night.

Another avenue of investigation could have been the BIW workers themselves. A second shift of BIW employees got off work about 12:10 a.m. May 24, around the time that Briggs was seen walking toward the pier with an unidentified young man.

Philpin also said the police did not endeavor to reconstruct what he described as the choreography of the crime – an attempt to re-create how Briggs and her killer moved through the crime scene, leaving behind the trail of clues that investigators found the next morning.

In a functional and well-run investigation, detectives are chasing all manner of angles at once.

“You start with your evidence, you start with your crime reconstruction,” Philpin said. “You do not start with a theory. And this is another area of compromise for this investigation. They focused their investigation on a small group of street kids.

“They figured they would get anything they needed to know from those street kids, and to me that was a terrible mistake.”

Matt Byrne can be contacted at 791-6303 or at:

Send questions/comments to the editors.