Whether it’s a 26,000-panel municipal solar array or just a few panels on the roof of a home, someone has to install solar systems for the lights to come on, and Kennebec Valley Community College in Fairfield is ramping up efforts to train workers to do that.

KVCC offers two levels of solar photovoltaic training: an associate program and a design and installation program. Nondegree programs launched in 2012, they are designed for those already in the industry and are seeking certification from the North American Board of Certified Energy Practitioners.

The programs give those enrolled a hands-on learning opportunity with a simulated roof and required safety precautions. Instructors Keven Vachon and Rich Roughgarden say the hope is to have KVCC become a center for this kind of training. As with most programs offered at the college, those who finish are expected to find employment fairly quickly.

“They will (get jobs), maybe not in Maine,” Roughgarden said. “The jobs have to grow locally if they want to stay here.”

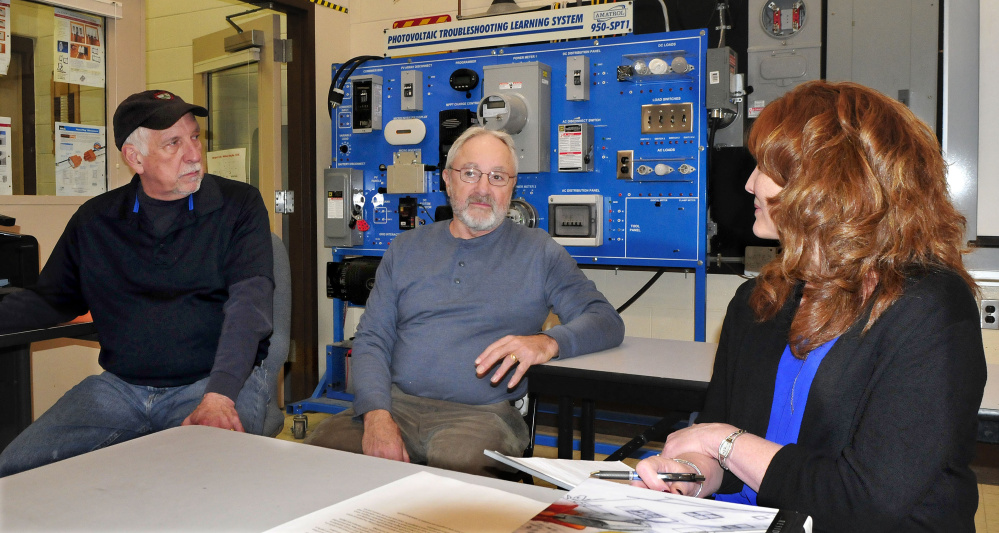

Officials say the solar design program at Kennebec Valley Community College in Fairfield is thriving. Speaking in front of a photovoltaic system are instructors Keven Vachon, left, Rich Roughgarden and program coordinator Robin Weeks on Thursday.

That’s the big problem for the solar industry in Maine: There’s the potential for future industry growth and jobs, but it’s still lagging behind the rest of the Northeast. Industry experts say Maine’s incentives for solar creation are among the worst in New England, even if the actual prospects for solar projects in central Maine are bright.

Garvan Donegan, the senior economic development specialist for the Central Maine Growth Council in Waterville, said central Maine is well positioned to be a player in large-scale solar projects going forward.

Donegan said central Maine has a number of things in its favor. He said there is a continued growth in the solar market that is tied to federal tax credits, which he expects to continue. Also, large tracts of land are available in this section of the state, as well as swaths of land near electrical substations.

“Central Maine does have strategic assets,” he said.

According to data from the Solar Foundation, which conducted a solar job census for 2016, the bulk of Maine’s solar jobs were located in Cumberland County. All told, there were 572 solar jobs in 2016, including installation, manufacturing and sales. This included 242 new jobs since 2015, a 73 percent growth rate.

However, the number of jobs dipped considerably in more northern areas. Somerset County reportedly had only eight jobs listed for 2016, and Franklin County reported just seven. Kennebec County fared comparatively better with 37 jobs.

The foundation, based in Washington, D.C., ranked Maine 40th in the country for solar jobs and 27th in solar jobs per capita.

Even so, central Maine is already home to the largest municipal solar array in Maine. The 26,000-panel array spanning roughly 22 acres in the Madison Business Gateway generates enough electricity to satisfy the needs of about 20 percent of Madison Electric Works customers. Superintendent Calvin Ames has said that on a sunny day, the farm meets the needs of “100 percent” of the utility’s customers – about 3,000 homes and small businesses, excluding Backyard Farms. The array was constructed by Ohio-based IGS Solar, and Madison Electric Works purchases all the energy it produces.

Two more large-scale utilities are in the works in nearby towns. Fairfield and Clinton have been eyed for farms that would generate enough power for 6,000 out-of-state homes combined and create more than 200 jobs locally.

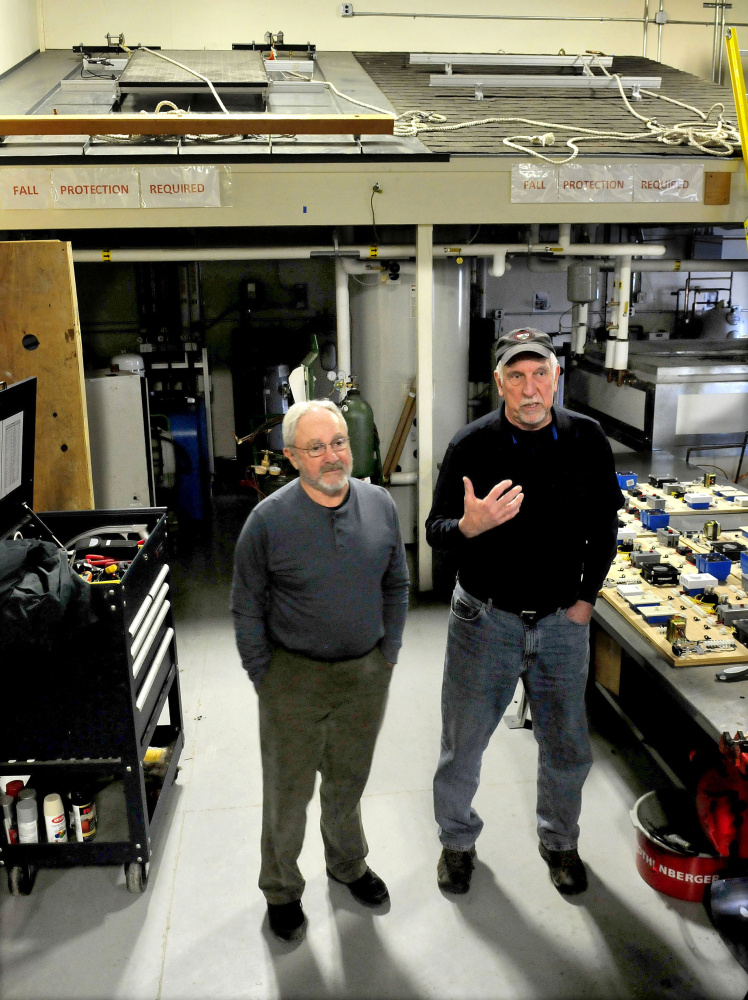

Solar Design instructors Rich Roughgarden, left, and Keven Vachon speak in front of a solar panel roof installation lab at Kennebec Valley Community College in Fairfield on Thursday.

Ranger Solar, based in Yarmouth, is planning for the projects in Fairfield and Clinton to generate 20 megawatts of power each, and the generated power will be sold to Connecticut. The farms, the exact locations of which have not been released, are each expected to cost around $20 million. Before sites are finalized, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection needs to investigate the sites.

At KVCC in Fairfield, Solar Program Coordinator Robin Weeks said the new programs are geared toward certification and are the only ones she knows of in the state to offer design and installation. The associate program, which she said was about providing the fundamentals necessary for jobs in the solar field, is worth 18 educational credits. The design and installation program is worth 40 credits. In order to take the certification exam, a person needs those 58 credits.

INDUSTRY UNCERTAINTY

Roughgarden, the instructor, is an electrical engineer who started his own company, Maine Solar Engineering, in 2008. He said he took entry-level classes toward certification at KVCC and eventually was certified. He and fellow instructor Vachon run the design and installation program, a 40-hour program broken up over the course of two Friday and Saturday workshops with eight hours of the program done online. Vachon, a master electrician, said he came to KVCC after teaching electrical programs in Waterville and became an adjunct professor at the college a decade ago.

Vachon said they would like to bring solar programs into high schools to gauge interest early on.

Weeks said that so far 161 people have gone through the nondegree solar technology program. She said the plan is to start a steering committee to see what the next steps for the program will be.

Roughgarden acknowledged that the uncertainty regarding future legislation makes planning for installers difficult. But, he said, even though Maine’s incentive climate for solar technology is the worst in New England, there are still local companies that hire.

Send questions/comments to the editors.