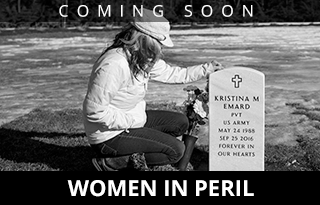

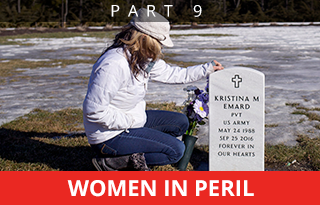

Ann Howgate visits the grave of her daughter, Kristina Emard, in Southern Maine Memorial Veterans Cemetery in Sanford. Emard was sexually assaulted by another soldier while serving in South Korea. After she returned to the U.S. her life devolved into drugs, and eventually death at age 28. Physical or sexual assault is a prime cause of opioid use by women, federal officials say.

Ninth of 10 parts.

For months, Ann Howgate frantically searched for a residential treatment bed for her daughter, an Army veteran facing jail time if she didn’t get into rehab for her drug addiction.

After checking with more than a dozen treatment programs in Maine, Howgate struck out. The programs were either full, with no beds available for a woman, or too expensive, or they wouldn’t take her insurance.

“It shocked me,” she said. “It totally shocked me.”

Her daughter, Kristina Emard, a former Army private whose life unraveled after she was raped by a fellow soldier, eventually got into residential treatment in Massachusetts, moving among several programs as she fought to stay clean and pursue her nursing studies. But she couldn’t get past her addiction, and she died of an overdose of fentanyl and cocaine in September 2016. She was 28.

When it comes to opioids, women are at a deadly disadvantage.

They are dying of overdoses at increasing rates compared with men. They get addicted faster and feel withdrawal more acutely because of their physiology. They are often dealing with sexual trauma as well as their addiction. They tend to avoid seeking treatment if they are mothers, because they fear their children will be taken away from them.

And when they do ask for help, there are fewer resources available for them. Less than a third of Maine’s 200 public treatment beds are for women, and they face long waiting lists to get into a program.

The barriers women face in Maine are reflected across the nation, prompting public health specialists to call for greater attention to women’s needs and more investment to reduce addiction’s deadly toll.

“Our mothers, wives, sisters and daughters are dying from these overdoses at rates never seen before,” said Karin Mack, an associate director of science at the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. “This needs to stop.”

SEXUAL TRAUMA, THEN SPIRALING DOWNWARD

Tina Emard wanted to be a nurse, but college was expensive. So she enlisted in the Army to get training and jump-start her education. She was working as a medical logistics specialist in South Korea in 2008 when she accused a fellow soldier of slipping a drug into her drink and raping her. Howgate, Emard’s mother, said four other women asserted he had done the same thing to them. When he went to trial a year later, Emard returned to South Korea to testify. The soldier was acquitted.

Howgate, who lives in the town of Lebanon, doesn’t know exactly what happened at the trial. But she knows what happened to her daughter.

At her new duty station in Georgia, she was accused of making false accusations against a fellow soldier because the man she accused of attacking her in South Korea was acquitted. Her work performance suffered, and her Army commanders gave her demeaning assignments, such as raking leaves and scrubbing toilets.

Emard began smoking marijuana and then moved on to other drugs, including methamphetamine. She was late for duty assignments and went AWOL twice. After the second incident, the Army gave her an ultimatum: Accept a general discharge or face a court-martial. Emard accepted the discharge in February 2012.

Ten months later she was arrested in Georgia on a felony drug possession charge. Howgate found a bed for her daughter at an 18-month, faith-based treatment program in Manchester, New Hampshire, and convinced authorities in Georgia to release her so she could obtain treatment.

Howgate was on her way to Georgia to pick up her daughter when the treatment offer was withdrawn. New Hampshire probation authorities didn’t want to take on Emard’s case.

The rejection sent Howgate on a desperate scramble for a bed in Maine.

“I tried for three months to find a place here, and nothing,” she said.

Place your cursor on a photo for buttons that allow you to pause or move ahead at your own pace.

- Ann Howgate says her daughter Kristina was so excited to be in the Army she even wore the uniform when she came home to visit. While serving in South Korea, Kristina was sexually assaulted by another soldier. Staff photos by Brianna Soukup

- Ann Howgate has kept the photo collages from Kristina’s funeral on display at her home.

- Ann sits in the car where Kristina overdosed on cocaine and fentanyl at 28. She often sits in the car, smelling the blanket that Kristina was covered with because it was the last thing to touch her daughter’s body.

- Kristina, in a family photo with Ann, went AWOL twice after her sexual assault in Korea and suffered from depression and anxiety.

- Ann’s home is filled with photos and memories of Kristina.

- Records from Kristina’s military career detail her 2008 sexual assault and Post Traumatic Stress disorder.

- Kristina sent a text message to her mother showing a side-by-side comparison of her mug shot from when she was using and a photo of her after being clean for one year. Kristina died in September 2016, and Ann has kept her daughter’s messages on her phone.

‘REALLY COMPLEX AND MESSY’ FOR WOMEN

The sexual trauma that drove Emard into a downward spiral is all too common among women who use heroin or other opioid drugs. It has been estimated that as many as 80 percent of women who enter treatment for drug abuse have experienced physical or sexual assault, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. For addiction treatment to be effective, it has to address not just the drug use but also the interconnected issues that women face, such as sexual or physical trauma and the challenges of child-rearing.

The shame surrounding sexual trauma and being a bad mother destroys self-confidence and independence. Women feel trapped by an addicted partner, or by a domestic abuse situation. Even if they are free to seek help, mothers can’t find child care so they can slip away for an hour for a 12-step meeting, let alone more extensive doctor’s appointments, counseling or residential care.

That’s why experts say effective recovery support for women should include safe housing, domestic violence services, child care, transportation, parenting support, and connections with other women in recovery.

“For men, it’s about getting clean and getting a job,” said Georgia Rose, a counselor of more than 30 years who works at McAuley Residence, a Portland residential program for women and children. “It’s really complex and messy” for women, she said. “There’s a lot more stigma with women. There are relationship issues. There is a lot of (sexual) trauma. It’s a really tragic thing.”

Nichole Curtis (in gray shirt) leads a Sunday night meeting at the sober house for women she runs in Portland. Curtis, who used alcohol and drugs, including opiates, for many years knows the challenges women face in recovery.

AN INTERMINABLE THREE-MONTH WAIT

Niki Curtis almost missed her chance at recovery.

FROM THE EDITOR

COMING TUESDAY: Waking up: As Mainers come to grips with the opioid crisis, what will the state do to help?

After years of shooting heroin and smoking bath salts, she tried to find a treatment bed in July 2012. Nothing was available. Crossroads, a women’s residential treatment center in Windham, said it would take her, but she would have to wait three months for a bed to open up. For an opioid addict, three months is an eternity, and Curtis used drugs aggressively, a common behavior for people who know they are going to have to stop using when they enter treatment.

Her courage dissipated and the passage of time weakened her resolve to get help. When Crossroads called a few days before she was scheduled to show up, Curtis started making excuses to delay her arrival. They gave her a deadline and hung up.

“I realized the opportunity was slipping away, so I called back,” she said.

Clean now for nearly five years, Curtis, 45, manages a sober house for women in Portland. Bewildered, she shakes her head at how fragile her first steps into sobriety were, and how difficult it is for women to get timely treatment.

“I’m horrified there are wait lists like that,” she said.

‘CRAZY INCENTIVES … AND DISINCENTIVES’ BUILT IN

There are powerful social pressures that dissuade women from seeking help.

Curtis said she’s still working through her “shame list” – childhood sexual abuse, drug use in her early teens, a partner pressuring her to shoot heroin, using her body to get drugs, and – worst of all – disappointing her son in the chaos of her addiction.

“We women have a shame that is different from a man’s,” she said. “I know I haven’t forgiven myself.”

VITAL SIGNS: Women seek help for drug addiction at about the same rate as men in Maine, yet barely a third of the state’s roughly 200 residential treatment beds are designated for women.

Addiction can be more severe for women because of gender differences in metabolism, absorption and elimination of drugs. They “get sicker quicker” than men, in what’s known as the “telescoping effect,” and are more prone to overdoses.

Poor and childless women are less likely to get insurance and treatment. Custodial parents can get MaineCare and pregnant women are guaranteed immediate treatment help, including going to the top of any waiting list. But if you lose custody, or go into long-term treatment without your child, you lose MaineCare.

There are “some crazy incentives built into the system – incentives and disincentives – like don’t go into treatment because you’ll lose your MaineCare. Get pregnant because you’ll get MaineCare. It’s nutty,” said Bob Fowler, executive director at Milestone.

Most of Maine’s public residential beds are exclusively for pregnant or parenting women – including all 16 beds at Crossroads and a 10-bed expansion at Wellspring in Bangor due to open this spring.

Many women won’t admit to an addiction if they think they’ll lose their children to the state.

“Their potential to lose children is very real, so they will keep it under wraps,” said Melissa Skahan, a vice president at Mercy Hospital in Portland who oversees the McAuley Residence. “Women are often forced to choose between getting help or acting as a mother.”

Substance use alone isn’t grounds to remove a child, but it can happen if the state can prove the child is experiencing abuse or neglect as a result of that substance use. In 2016, state officials removed 411 Maine children from homes because of parental substance use, a 45 percent increase since 2009.

Miranda McCue, 21, sits on a bed in her shared room at Milestone, a detox center in Portland. McCue spent almost a week detoxing from opioids, and in January was making daily calls to try to find a residential program for women. After treatment, she hoped to complete the requirements for her college degree and get to know her 2-year-old daughter without being under the fog of drugs.

CHILD CARE AS A KEY BARRIER TO TREATMENT

In response, many women’s drug treatment residential facilities now allow women to bring their children, even for extended programs like the two-year one at McAuley Residence.

“In the mid-’90s, one of the No. 1 barriers for women seeking addiction treatment was lack of child care,” said Mary Anne Roy, the chief clinical officer at Crossroads, which now has on-site child care and parenting classes. “That prevented women from seeking treatment, and that remains true today.”

Miranda McCue, 21, said her 2-year-old daughter is a big reason why she finally sought help.

She’s been using drugs since she was 13, when she took a Vicodin at a party. That first pill led McCue to try any available street drugs in the small Waldo County town of Knox before she settled into a multi-year, $200-a-day habit of smoking oxycodone.

“I’ve pretty much used every day since I was 13,” she said. “If I wasn’t on drugs, I was just looking for them.”

Now sober for the first time in many years, she’s hoping to complete the requirements for her college degree and get to know her daughter without being under the fog of drugs.

In January she was at the Milestone detox center in Portland, making daily calls to try to find a residential program for women.

“If I go home, I’m using,” McCue said flatly, referring to the accessibility of drugs there. “Going home equals getting high.”

News Assistant Melanie Creamer contributed to this report.

Send questions/comments to the editors.