For Corey Coburn’s sister, Meghan Stuart, and their mother, Heidi-Sue Stuart of Lisbon, the pain of his overdose death in November 2015 is still raw. “You could see that he wanted to get better,” Meghan says of her brother, who had faced numerous obstacles, including a lack of insurance, in his attempts to get treatment. All told, federal officials say, there are 25,000 to 30,000 people with addiction in Maine who can’t get the help they need.

Fifth of 10 parts.

Before he overdosed on fentanyl and died on his bedroom floor in November 2015, Corey Coburn had been in and out of treatment for opioid addiction several times.

He enrolled twice in an intensive outpatient program, which included counseling and medication. He was thrown out the first time for smoking pot, and he relapsed shortly after completing the second program.

His family tried to get him into a residential center, even out of state, but they couldn’t get a bed. Coburn didn’t have insurance, and the family couldn’t pay. His criminal history, minor offenses all tied to his addiction, disqualified him for some programs.

Coburn’s sister, Meghan Stuart, said the family became frustrated by the obstacles to treatment.

“You could see the desperation,” she said. “You could see that he wanted to get better.”

As Mainers die in record numbers from overdoses, a simple question emerges: How do we treat their addiction before it’s too late?

The answer is anything but simple.

Among more than 100 families of overdose victims and people in recovery interviewed by the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, scores said they faced waiting lists or other barriers to treatment, much like Coburn’s family. All told, there are 25,000 to 30,000 people with addiction in Maine who can’t get the help they need, according to the federal agency that oversees substance abuse funding.

The demand for in-patient treatment beds far exceeds the supply, which has remained relatively unchanged – about 200 Medicaid-eligible beds – for more than a decade. The demand for Suboxone, the leading medication to treat opioid addiction, exceeds the number of doctors who can prescribe it. And the cost of virtually any kind of treatment exceeds the ability to pay among the uninsured or low-income Mainers who make up a large share of those struggling with addiction.

For several years, the administration of Gov. Paul LePage made it more difficult to get treatment, by tightening eligibility for MaineCare, cutting reimbursement rates for methadone providers and opposing more access to Narcan, an overdose antidote.

Compounding these problems is a disagreement – among treatment providers as well as people in recovery – about the best method.

Research has shown that the most effective treatment combines medication with intensive outpatient therapy. Yet many programs still follow an abstinence-based, 12-step model that has been used for alcohol addiction since the 1930s.

These programs, such as Ocean House Sober Living in Portland, won’t accept patients who are using medications like Suboxone or methadone to treat their opioid dependence because they don’t believe they are effective.

Greg Lowell, Ocean House’s program director, acknowledged that there is a natural tension between those who advocate for medication and those who advocate for abstinence but he said the most important thing is that more people are talking about it from all sides.

“Hopefully, people understand and respect that everyone’s path is going to be different,” he said.

Thomas Kivler, behavioral health director at the Addiction Recovery Center at Midcoast Hospital in Brunswick, said treatment need only be compassionate and judgment-free.

“The biggest thing is access, and that’s getting people into the door,” he said. “But we also don’t kick people out for being symptomatic. We assume that is part of what addiction is. You relapse, you get back up. That hasn’t always been an easy sell.”

‘PEOPLE DON’T HAVE THE RESOURCES THEY NEED’

Three people enrolled in the treatment program at the Addiction Recovery Center, or ARC, spoke with the Press Herald about their experiences. They agreed to share their stories if their last names were not used because they worried that speaking publicly might affect their jobs or bring embarrassment to their families.

Derek got hooked on pain medicine in his early 20s, after multiple surgeries on his knees left him hobbled. He had been taking pills for so long he didn’t know how dependent he’d become until his doctor stopped prescribing. Pills turned to heroin, and suddenly he was 30 years old wondering how things had gotten so bad.

FROM THE EDITOR

COMING FRIDAY: Vulnerable in recovery: Shannon Long’s story illustrates how fragile sobriety can be

Melody was prescribed painkillers after shoulder surgery, and when the prescription ran out, she found her body still craving the feeling they gave her so she sought them elsewhere. Luckily, she avoided heroin but was headed down that path.

“Addiction runs in my family,” she said. “I should have known. I didn’t listen to myself.”

Jessica wasn’t introduced to opioids through a prescription, but her story is equally common. She was a young adult experimenting with substances and someone had Vicodin. She didn’t get hooked right away but came back to it later, then got into heroin.

All three said Suboxone, which reduces the cravings of addiction and limits withdrawal symptoms, has given them back their lives. They don’t know how long they’ll have to take the medication, but they hope more people see it as an option.

“I’m sick of people dying,” Jessica said. “If people are afraid, they need to understand that they can do this.”

Drug users who want to get clean without medication-assisted therapy face a serious challenge. They might do well in a residential center, but openings are hard to find and hard to pay for. And most abstinence-based residential programs last only about a month, after which the person in recovery is sent back to the same environment where their addiction took root.

Leah Bauer, the medical director at ARC in Brunswick, said some patients aren’t the right fit for Suboxone and might be better suited to methadone. But there is no methadone clinic nearby. Similarly, some might need a residential facility, particularly if they don’t have supportive recovery environments. But there are so few beds and the ones that are available have long waiting lists.

“The most frustrating thing is that people don’t have the resources they need,” she said.

FAILURE TO INVEST IN TREATMENT COMES AT A PRICE

Efforts to increase spending and access to treatment have consistently lagged behind the problem in Maine.

The LePage administration has recently committed to $5.4 million in new state spending for medication-assisted treatment. The funding will provide help to an estimated 750 additional Mainers who are uninsured or on MaineCare.

It’s the first significant state investment in treatment since the opioid crisis accelerated in 2013. For several years, the administration focused on hiring more drug agents, and it directed federal money toward prevention, rather than treatment. Among policymakers, it’s generally agreed that law enforcement and prevention are key components in fighting addiction, along with treatment.

But the state’s failure to invest quickly in more treatment came at a price. In the three years that the administration was focused on enforcement and prevention, overdoses killed 858 people.

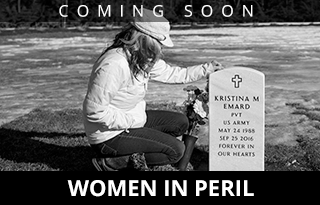

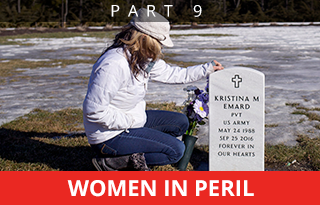

Corey Coburn and his sister, Meghan Stuart, pose in a photograph in the Stuarts’ Lisbon home. When he wasn’t using, Corey was funny and very compassionate – the kind of person who once hugged a crying stranger who had just struck his car, telling her, “Everyone makes mistakes.” Corey overdosed on fentanyl in November 2015; he was 28.

Maine treatment admissions for opioid addiction actually declined from 7,483 in 2013 to 6,372 in 2015, according to the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. A major contributor to the decline was the state’s decision to narrow MaineCare eligibility, which removed 19,000 people from the program.

Corey Coburn was 28 when he died. His parents couldn’t afford to keep him on their insurance when he was a young adult and, since he was neither disabled nor a parent, he was not eligible for MaineCare.

Experts say it’s not clear yet whether states that expanded government health care have had more success battling the opioid crisis. But states, such as Vermont, for example, which invested heavily in treatment in 2014, have at least seen the number of overdose deaths level off – although there was an increase in overdoses in Vermont last year, after a period of stability.

Without insurance, methadone can cost about $300 each month and Suboxone can be as much as $600 a month. But that’s just for the medicine. Counseling appointments and drug tests add to the cost, although many places offer a sliding scale. Residential treatment facilities can cost thousands of dollars for a 30-day stay.

‘LIKE RUNNING A RESTAURANT WITHOUT FOOD’

Treatment providers have been advocating for more spending on medication-assisted treatment for years, but only recently have there been investments in new or expanded programs.

Eric Haram, an addiction treatment consultant and former head of the Maine Association of Substance Abuse Providers, said many providers still don’t understand how medication-assisted treatment works.

“In this day and age, to run an addiction clinic without medication-assisted therapy is like running a restaurant without food,” he said.

Not everyone agrees.

Lowell, who manages the two sober-living houses in Portland, said he doesn’t believe medication truly allows people to manage their addiction. As a former heroin addict himself, he has used both types of treatment.

“If we’re talking about harm reduction: Sure, those (medications) are valuable, but I don’t think it’s a long-term solution,” he said, adding that the financial incentive for providers to have patients stay on medication is strong.

One major concern with a cold turkey, abstinence-only approach is that if a person relapses, which is common for opioid users, they are at much higher risk of overdose because their tolerance has weakened. Many family members of overdose victims said their loved one overdosed immediately after a period of sobriety.

VITAL SIGNS: As the heroin crisis deepened, state funding on substance abuse treatment declined by 7 percent. From 2011 to 2015, total substance abuse expenditures fell from $76.7 million to $71.6 million, with much of the decline coming in spending on MaineCare, the state’s version of Medicaid.

Tom Parks of Saco thought his daughter Molly was doing OK. She had gone through a residential rehab in New Hampshire, her third attempt, and was starting to feel like she could beat her addiction.

But when she got out, she hadn’t escaped the culture. Her dad said her dealer offered to give her drugs for free just to get her back. She fought him off for only so long. Molly never really tried methadone or Suboxone until her final stay in rehab. Her dad said she always tried to white-knuckle it. She was tough that way.

Not long after she left the rehab facility, she could feel herself slipping, Tom said. In early 2015, she got a prescription for Suboxone. She went back in the next month for more but never took it.

When family members cleared her apartment after she died, they found the Suboxone in a bag from the pharmacy, still stapled closed.

DOCTORS HAVE ENORMOUS RESPONSIBILITY TO LEAD

Heidi-Sue Stuart comforts her only surviving child, Meghan Stuart. Corey Coburn, her son and Meghan’s brother, overdosed on fentanyl in November 2015. Heidi-Sue’s other child, Hannah, died from a rare disease at the age of 3. Meghan says her mother is the strongest person she knows.

Recent investments in medication-assisted treatment, along with a gradual willingness among more doctors to prescribe Suboxone, offer hope, but there are still challenges.

The number of doctors who have federal waivers to provide Suboxone increased from 32 in 2011 to 119 this year, but that still represents only about 5 percent of primary care physicians.

Recent federal rules were relaxed to increase the cap for doctors from 100 patients to 270 patients and also to allow nurse practitioners and physician’s assistants to obtain waivers but there is no requirement.

Ann Dorney, who has a family practice in Skowhegan, has been seeing patients with opioid addiction for about 12 years and demand has grown significantly.

“Sometimes five people a day call my office looking,” she said.

Dorney has heard other doctors express concern about opening their practice to people with addiction but said that’s shortsighted.

“In reality, they are seeing these people already. They just don’t know,” she said. “There is a lot of work. It’s gratifying, but it’s not easy.”

Noah Nesin, chief medical officer at Penobscot Community Health Care in Bangor, said doctors have an enormous responsibility to lead when it comes to treatment and many have failed.

“We contributed mightily to this,” he said. “Family doctors were the biggest prescribers of painkillers.”

The Maine Medical Association recently has begun holding workshops around the state to educate doctors about medication-assisted treatment. In rural areas, access to a doctor who prescribes Suboxone, and to a counselor who provides the critical outpatient therapy to complement the medication, will be a key challenge.

There remains, too, the persistent feeling that using drugs to treat drug addiction is wrong. Many people in recovery share stories about others who sell their Suboxone on the street or even exchange it for heroin. And the knowledge that the pharmaceutical companies that benefited greatly from sales of opioid painkillers – which helped create the current crisis – also profit from Suboxone and methadone sales undermines support for medication-assisted treatment.

In-patient treatment can be an option for those who object to using medication, but there have been virtually no investments in affordable treatment beds in Maine for years.

Corey Coburn once made his little sister, Meghan, a package of redeemable coupons for her birthday. They still make her laugh – and cry.

ANY BARRIER CAN SEEM LIKE TOO MUCH

Getting people in the door is often the hardest part. Any barrier, no matter how small, is going to seem insurmountable.

Like so many others battling addiction, Corey Coburn’s family said his run-ins with police made it harder to find treatment. If he had gotten help before he ended up in the criminal system, maybe it would have made a difference.

But support after sobriety is just as crucial.

Shortly before he died, Coburn’s family said he appeared to be working hard at staying clean. He started going to church and volunteering in the soup kitchen. He put on weight. He found a new girlfriend and a new job.

None of it saved him. He stopped asking for help because he was embarrassed about failing so many times.

“There needs to be more help offered,” said his sister Meghan. “I don’t know how beneficial the programs were for Corey. Sometimes he made more (drug) connections (at the programs) than when he was in jail. There needs to be a more long-term solution, more counseling after the fact. There needs to be more follow-up.”

Staff Writer Mike Lowe contributed to this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.