Place your cursor on a photo for buttons that allow you to pause or move ahead at your own pace.

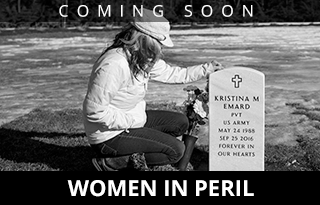

- Sitting on the bed of the daughter she lost to a methadone overdose in 2013, Gail McCarthy of Stetson inhales the lingering scent from the clothes her 24-year-old son, Matthew, was wearing when he died of a fentanyl overdose just a year and a half after 21-year-old Ashley’s death. Among the more than 100 families of overdose victims interviewed by the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram since the summer of 2016, at least seven had lost more than one person to the epidemic. Staff photos by Brianna Soukup

- Within the span of about 18 months, McCarthy lost both Ashley, 21, and Matthew, 24, to opiate overdoses.

- McCarthy can’t bring herself to wash the clothes Matthew died in because they still smell like him.

- McCarthy goes through a plastic container filled with childhood mementos of her children, including a card made by Matthew.

- McCarthy begins to cry in her daughter’s old bedroom at her home in Stetson. Ashley McCarthy died from an overdose in her bed and Gail laid with her daughter until paramedics arrived.

- A quote Ashley added to her Facebook wall before she died now hangs in her old room. Addiction strikes some families repeatedly because it is driven largely by a combination of genetics and environmental factors.

Second of 10 parts.

On workdays, Gail McCarthy drives 70 miles to her job and then another 70 back home.

It’s a lot of time alone in the car with her thoughts, and they often go to the same place.

“I can’t even listen to the music,” she said of her drive between Stetson and Rockland. “I’m too worried a song will come on that will make me think of them and I’ll start shaking and lose control.”

There is no preparing for the pain of losing a child, and McCarthy knows that pain twice over.

In November 2013, she lost her daughter, Ashley, to an overdose of methadone, which she bought on the street to avoid withdrawal symptoms from heroin addiction. She was 21.

About 17 months later, her son, Matthew, died of an overdose of fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid. He was 24.

As the drug crisis has ravaged Maine, claiming hundreds of victims, few families have lost more in such a short period than the McCarthys.

An overdose death is not like a car accident or a lost battle with cancer. Often, families watch loved ones in the grip of addiction turn into completely different people. They watch them struggle to break free from the drugs, only to slip back down again. The roller coaster of addiction carries not only the user, but also everyone close to them.

In some instances, family members even admit to feeling a sense of relief after a death.

“There is a sense of peace,” said Patty Dumont of Poland, whose son, Nicholas Douglass died in December 2015 from an overdose at age 25. “You don’t have to worry anymore. Just watching the news, wondering if my son’s name was going to be on the news every day. Waiting for the phone call that I received.”

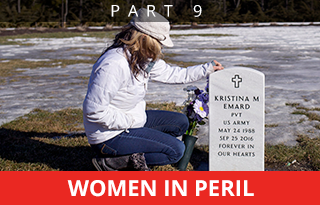

Among the more than 100 families of overdose victims interviewed by the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram since the summer of 2016, at least seven had lost more than one person. In some cases, those who died were siblings. In others, they were parent and child.

Many more families of overdose victims had children or parents still living who were addicts.

Leigh Haskell, a clinical psychologist in Portland who specializes in grief counseling, said the incomparable pain of losing a child or parent to drugs is often compounded by a sense of bewilderment and helplessness.

“Many families come to realize that they didn’t know the severity of the issue or how long it had been going on and that can be shocking,” she said. “And for families that did know and tried with all their might to get help, it’s anguishing that despite all those efforts, it didn’t work.”

Haskell has seen a noticeable increase in the last five years in clients who have lost loved ones to addiction. She said the one thing family members of overdose victims have in common is shame, and that often prevents people from speaking out.

“What I tell them is to seek out the people you feel understand,” she said. “Focus less on the people who you think are judging you.”

Addiction strikes some families repeatedly because it is driven largely by a combination of genetics and environmental factors. Children who grew up in families scarred by alcohol or drug abuse, divorce, poverty, or physical or sexual abuse are much more likely to develop addiction, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

“Carrying a genetic burden does not necessarily mean that a person will get the disease,” said Vivek Kumar, who studies the genetics of addiction at The Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor. “Environment is key, but its influences are harder to quantify. There are cultural and social norms that are not under our control.”

A child or teenager might see substance use in the home or among friends, realize that it’s wise to stay away, and yet still gravitate toward that behavior because it’s what they know.

Gail McCarthy’s children, Matthew and Ashley, are memorialized on candles at her home in Stetson. Even after her daughter died, her son continued to use drugs, McCarthy said, and she remains angry that they couldn’t get him the help he needed before it was too late. “There is no help out there,” she said.

Even when a family member sees someone close to them struggle mightily with addiction or die from overdose, they can’t always stop.

That’s how it was for Matthew McCarthy.

Still stuck in the nightmare of her daughter’s death, Gail McCarthy remembered telling her son, through tears, “Promise me you’ll never do these drugs. I can’t lose two kids.”

“And he said, ‘I promise, Mummy. I promise,’ ” she said, sobbing.

Matthew couldn’t keep that vow.

When McCarthy is sad, she lies down on her daughter’s old bed, still neatly made inside her home, so she can be close to Ashley. Or she opens a plastic bag that holds the clothes Matthew was wearing when he died, so she can smell him.

Her family will never be whole again and every time she reads an obituary or hears about another overdose, she aches for the parents.

Some days, McCarthy isn’t filled with sadness but with anger. Anger that her children, who were raised in loving though far-from-perfect homes, turned to drugs. Anger that they couldn’t get help before it was too late. And most of all, anger that there were people out there so willing to sell her babies substances that could kill them in an instant.

She knows exactly who sold the drugs to both of her children. For a long time, she wanted them to pay.

SIGNS OF TROUBLE: ‘I SHOULD HAVE KNOWN’

FROM THE EDITOR

COMING TUESDAY: Disease or bad behavior: Does addiction call out for compassion or punishment?

Ashley and Matthew McCarthy were raised in Hampden, a mostly affluent suburb of Bangor.

They lacked for nothing, and McCarthy said she never really worried about them because they were always honest with her. She knew they drank and smoked pot.

“I used to think all these parents had their head buried in the sand. How stupid,” she said. “Boy oh boy, until it’s your family.”

Ashley was prescribed opioids after being diagnosed with painful uterine cysts. Her mother thinks that’s how she got hooked.

She started stealing to support her habit. A week before her daughter died, McCarthy slapped her during an argument over her drug use. It was the first time she had ever done anything like that. She was so frustrated. She didn’t know how to reach her.

A few days later, they reconciled. Ashley needed help. She needed her mother.

The day before Ashley died – Gail’s birthday – they spent together shopping in Bangor. Ashley didn’t have any money but wanted a journal, so McCarthy bought it for her. It was a white book with pastel polka dots on the cover. She told her daughter to write in it every time she thought about using.

Ashley never got to open it.

McCarthy started writing in it herself on Nov. 21, 2013, the day after Ashley’s overdose.

Matthew started using opioids before Ashley, McCarthy said. She thinks it was his senior year of high school. He stopped playing hockey, which he loved, and started losing a lot of weight.

“I should have known,” McCarthy said. “He lived and breathed hockey.”

When Ashley died, Matthew took it hard, his mother said, but she didn’t know how hard.

Even though she pleaded with him, Matthew kept using.

“We called all these places, trying to get him help,” McCarthy said. “They told us we needed to wait or we had to call back and that was just to get him into Suboxone. Everything was just going to take so long and he needed it immediately.”

VITAL SIGNS: In early 2016, lawmakers approved funding for a 10-bed detox center in Bangor. It would be only the second detox center in Maine, alongside the 16-bed Milestone facility in Portland. But more than a year later, the Bangor center has yet to open.

The day Matthew died, McCarthy had gone to a counseling session after work. When she got the call on her cellphone to come home, no one told her why, but she knew. She had bought a cake to celebrate what she thought was one week of being clean for Matthew. Written on it was, “I’m proud of you.”

She got to the house. The ambulance was still there, which she knew was bad news. If they had saved him, the ambulance would have taken him to the hospital.

His body was still in the bathroom. His mouth was open. His tongue was white.

“I thought, ‘My big baby. He’s got to be so cold,’ ” McCarthy said through tears. “Why did I think these stupid things? So I went into the bedroom and got a blanket and put a pillow under his head. And then I laid down beside him.”

FOR FAMILIES IN CRISIS, COMMON FRUSTRATIONS

McCarthy and her husband got divorced in 2013, not long before Ashley’s death. She doesn’t know whether the divorce contributed to her children’s substance use but said they took the split hard.

The parents tried to get help for both kids at different times but never had insurance or the money to pay for what they probably needed. What little help they did get wasn’t enough. There wasn’t any follow-through.

“There is no help out there,” she said. She was tempted to call the cops on each of her kids. But then what? Have them sent to jail, where they wouldn’t be treated? Or risk a criminal charge that would affect their futures?

Other families had the same frustrations.

The Fecteau family in Biddeford has been struggling to navigate the mire of Maine’s opioid crisis. Cathy Fecteau, right, lost her son Matthew to an overdose last summer. He was 27. Two of his siblings, an older brother and his younger sister, Lizzy, left, are also fighting opioid addiction, but the quest for treatment can be frustrating and sometimes fruitless. Matthew’s brother graduated from a detox program with these instructions: “Go find a doctor.” Listen to Cathy’s story.

Matthew Fecteau of Biddeford, who died last summer of an overdose at age 27, has two siblings, an older brother and a younger sister, who have both struggled with addiction, their mother, Cathy Fecteau said.

The family has struggled to find treatment, too. In one instance, a relative helped them buy Suboxone on the street because they couldn’t find a provider. In another, Matthew’s brother graduated from a detox program with instructions to “go find a doctor.”

Matthew also got stuck in the criminal system. He was out of jail less than two months when he overdosed and died. Near the end, he was more focused on getting help for his sister than himself, his mother said.

Paula Cahill of York lost her husband in 1999 to a cocaine overdose. She raised three sons on her own after that.

“I did everything I could do not to have them turn out like their dad,” she said.

But all three battled addiction and she did, too, for a time.

In 2015, her middle son, Joseph Cahill, overdosed on fentanyl and died. He was 27.

“You can’t put a cake in front of a person who is addicted to food and say don’t touch it,” said James Cahill, the oldest brother, explaining how prevalent drugs were. “When you put a drug addict in front of people who are doing drugs, they are going to say ‘yes’ eventually.”

Haskell, the Portland psychologist, said support is lacking not only for people who are struggling with addiction, but also for those who are struggling to cope with the grief of losing family members to an overdose.

“The reality is that people never completely go back to the way it used to be,” she said. “They get better at managing their lives without the lost person, but there isn’t a fixed point. You just get more able at living with the loss.”

A GRIEVING MOTHER, COMING TO TERMS

Even into 2016, Gail McCarthy still had a great deal of anger about what happened to her children. She kept thinking about confronting the two people who sold them their fatal doses.

McCarthy found out about her son’s dealer because of all the text messages in his phone.

Within the span of about 18 months, Gail McCarthy lost both Ashley, 21, and Matthew, 24, to opiate overdoses.

Eventually, the dealer was arrested for drug trafficking and she showed up in court on the day of his sentencing.

“The first thing I said to him was, ‘You should get the death penalty. An eye for an eye. You took my son,’ ” she said. “And he was crying and saying how sorry he was and that Matt was a good man, and then I realized, he’s just a kid. He’s just a kid. He wasn’t this monster. He was somebody else’s son.”

Before she left the courthouse that day, McCarthy gave him a hug.

She never got to meet the dealer who sold Ashley the methadone that took her life. In January, he died of an overdose. He was 27.

McCarthy found no solace in the news. Instead, she felt pain for his mother, whom she knew. Hampden is a small town.

She didn’t know how to reach the woman, so instead, she found the obituary online and posted a message.

She expressed sorrow for the woman’s loss.

“You know I lost Matt and Ashley the same way,” she wrote. “I would love to talk to you and we could share. I might be able to help you thru this. Please call me.”

McCarthy hasn’t received a response yet. Maybe someday she will.

Staff Writers Mary Pols and Kate McCormick contributed to this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.