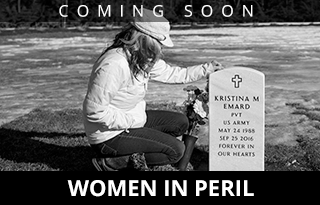

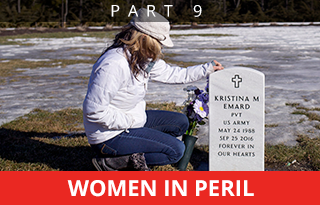

Behind the wheel of her daughter’s car this month, Ann Howgate of Lebanon clutches the blanket that EMTs used to cover Kristina Emard after she was found dead in the vehicle on Sept. 25, 2016. Howgate had desperately sought treatment in Maine for Kristina, 28, an Army veteran who suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and died from an overdose of cocaine and fentanyl, a powerful opioid.

First of 10 parts.

Dr. Mary Dowd slid into a chair inside the Portland offices of Catholic Charities and surveyed the list of patients, all battling opioid addiction.

There was Rachel, a 40-year-old mother of three balancing her sobriety with a toxic relationship with her ex-husband. And Michael, 32, anxiously awaiting the birth of his second child and celebrating seven months free of heroin, hoping many more months lie ahead. And Tanya, 34, working two jobs to pay for her medication-assisted treatment and save for a down payment on a new house.

There was Shannon, 32, who confessed to a recent relapse after nine months clean. She wasn’t happy about the setback but said she could have easily “gone on a run” of destructive drug use. She came to see Dowd instead.

She knew she’d fail a drug test but said, “I want to be held accountable.”

There was Andrew, also 32, who had recently completed a detox program and was soon to check into a 45-day residential treatment center in Auburn, a prospect that terrified him.

“I’ve been trying to shake it on my own,” he told Dowd, pausing to look down, his voice lowering to a whisper. “I just couldn’t do it.”

It was a Wednesday morning in January but it could have been any day of any month in any of the last few years. This is how Dowd spends them.

Many people struggling with addiction find treatment and regain their lives. She sees it every day. Those are the lucky ones.

But it’s the people she never gets to see who frustrate her. The ones who don’t make it. The ones who are dying in unprecedented numbers.

They are dying in the potato fields of Aroostook County and the lobster-fishing harbors Down East. They are dying in the western Maine foothills where paper mill closures have sown economic anxiety. They are dying in cities like Portland and Lewiston and in the suburbs, where opioids are in plentiful supply.

The death toll reached 376 in 2016, driven almost entirely by opioids – prescription painkillers, heroin and now fentanyl, a powerful synthetic. More than one victim per day. More than car accidents. Or suicide. Or breast cancer.

Only four years ago, there were 176 overdose deaths, less than half the 2016 total. Twenty years ago, just 34 people died from drug overdoses.

But in the last few years, the crisis has been more acute here than almost anywhere else. From 2013 to 2014, Maine saw the third-highest increase in any state, 27 percent.

The following year, 272 Mainers died from overdose, a 26 percent increase, putting the state behind only New Hampshire, North Dakota and Massachusetts in the rate of increase. That gave the state an overdose mortality rate, adjusted for age, of 21.2 per 100,000 people.

Comparable state-by-state data has not been compiled for 2016 but the recent numbers for Maine, where deaths increased by another 39 percent, suggest the trend is worsening.

It shows no signs of stopping.

The list of deaths would be longer if not for the increased availability and use of the drug Narcan, which reverses the effects of an opioid overdose.

In 2016, rescue workers used Narcan 2,380 times, up from 1,565 the year before, according to state data. Republican Gov. Paul LePage has been critical of Narcan and has used language that suggests people get what they deserve and shouldn’t be saved after a couple of overdoses.

The hardest part for Dowd and the many others like her throughout the state who treat addiction every day isn’t the number. It’s the sense that Maine hasn’t seen the worst of it yet and an entire generation is at risk of being lost.

“I don’t know how we can just sit and watch this happen,” said Dowd, who is soft-spoken by nature but passionate in bursts. “Where is the outrage? Where is the urgency?”

CONFRONTING ADDICTION: SOCIETY’S ‘MORAL TEST’

Shortly after delivering the eulogy, Angela Fauth of South Portland bends to kiss the casket of her cousin Randy Ouellette during his burial service last month at New Calvary Cemetery in South Portland. Ouellette, a popular bartender at Blackstones in Portland, died alone in his apartment of an apparent heroin overdose on Jan. 29. He was 42.

A yearlong Maine Sunday Telegram/Portland Press Herald examination of the opioid crisis and the collective response reveals that the state was largely unprepared, particularly for the increased demand for treatment, and is now trying to catch up.

For several years as the problem worsened, policymakers – led by LePage – made it harder to get treatment, not easier. They reduced reimbursement rates for methadone, a drug used to treat opioid addiction. They tightened eligibility for MaineCare, the state’s version of Medicaid, leaving many low-income people without the ability to pay. They fought increased access to Narcan, prompting Attorney General Janet Mills, a frequent adversary of the governor, to sidestep him and use funds her office controls to provide the overdose drug to local police departments.

In a radio interview in mid-March, LePage accused Democrats of blocking his efforts to increase treatment for opioid addiction. The governor’s assertion, which contradicts his previous opposition to more treatment spending, heightens the partisan conflict over an issue that was already dividing policymakers along party lines.

Until recently, there has been little increased spending on treatment to tackle the crisis. What new spending has been authorized hasn’t had an impact yet or has been offset by cuts elsewhere. The LePage administration agreed last December to spend $2.4 million for medication-assisted treatment for uninsured Mainers, many of whom lost insurance during cuts to MaineCare. And in February, the administration worked with lawmakers to add $4.8 million more for treatment into a supplemental budget.

COMING MONDAY: Families hit hard: For some caught in crisis, tragedies multiply

About 15,500 people received opioid addiction treatment in Maine in 2015, according to the state Department of Health and Human Services. But the total number of Mainers addicted to opioids is unknown. The Office of the Surgeon General estimates that, nationally, only 10 percent of people living with addiction get treatment.

And despite a consensus that addiction has reached epidemic proportions, policymakers and treatment specialists – even among themselves – are not united on a solution, even as deaths reach unprecedented levels.

The state has hired more drug agents, which has led to many more arrests and heroin seizures, but those efforts didn’t address demand or stop the overdose death rate from rising.

Perhaps the biggest barrier to overcome remains societal perceptions. Though a well-documented body of scientific research shows that addiction is a chronic disease of the brain, many still see it as a choice, a bad behavior that represents a character flaw or moral weakness. From this perspective, addiction is not a condition to be treated but a stigma to be hidden or denied.

Neither LePage nor Department of Health and Human Services Commissioner Mary Mayhew agreed to be interviewed by the Telegram and Press Herald for stories about the opioid crisis. The administration has long been critical of the newspapers, accusing them of having a liberal bias.

Others, however, say every day that passes is a missed opportunity to save lives. They say the solution isn’t one thing. It’s more of everything. More treatment beds. More medication-assisted treatment. More education and prevention. More money for people who don’t have insurance. And mostly, more compassion.

Because recovery isn’t a straight line. People stumble and fall. Sometimes they stumble and fall many times.

Dr. Vivek Murthy, the U.S. Surgeon General in the final two years of President Obama’s administration, published a report on addiction in November – the first of its kind. In it, he called for a fundamental shift in the conversation. He said the societal response will be a “moral test” for the country.

“There are millions of people living in the shadows,” Murthy said in a Telegram interview. “Many don’t want to talk if there is a camera nearby. They worry about losing their job or being ostracized by friends. And I understand that but that’s not the environment we need.

“It’s so important for individuals to step up and share their stories,” he said. “They remind us that we can’t be satisfied with incremental progress. Because lives are at stake.”

In 2015, a total of 52,404 lives were lost, 33,091 from opioids alone. That’s up 11 percent from the previous year and nearly triple the total from 1999. At the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the annual U.S. death toll peaked at 50,786.

By comparison, 37,757 people died in car crashes in 2015. The number of gun deaths, including homicides and suicides, totaled 36,252.

“I spent a lot of time being terrified,” says Lynn Ouellette, whose 22-year-old son, Brendan Keating, died of an overdose on Dec. 16, 2013. “People know what happened in the end,” the Brunswick woman says, “but they don’t know about the terror leading up to it. It’s like being on a plane you’re always worried is going to crash.”

THE HUMAN IMPACT: FRACTURED LIVES

Over the course of a year, the Telegram and Press Herald interviewed more than 100 families who lost someone to an overdose or had a family member in recovery. The families shared their stories of lost loved ones, 60 of whom were profiled by the newspaper.

Collectively, they revealed much: that people know very little about opioids until they are forced to learn; that opioids take over a person’s life in a way no other substance can; that effective treatment is hard to find and even harder to pay for; that addiction can happen in any family.

Many spoke of the overwhelming guilt and shame that are paired with addiction, how hard they are to overcome, and how it is time to reframe the conversation. Because often lost in the debate over addiction policy – a debate sometimes driven more by ideology than scientifically sound practices – is the human impact of the opioid crisis.

Families are left to agonize about what went wrong. Children grow up without a parent. Lives are fractured, perhaps irreparably.

Lynn Ouellette’s son, Brendan Keating, died from an overdose in December 2013 – as the addiction problem was just beginning to develop into a full-blown crisis.

There are things Ouellette will talk about when it comes to her son. How he got a tattoo of her last name while she was going through breast cancer. How he built her a beautiful walkway shortly after he graduated from masonry school.

But she still doesn’t share the details of finding the 22-year-old unconscious from an overdose in the basement of her Brunswick home.

“It’s still too hard,” she said. “But I was always terrified that’s how it would end. I spent a lot of time being terrified. People know what happened in the end but they don’t know about the terror leading up to it. It’s like being on a plane you’re always worried is going to crash.”

In a bedroom of Heidi-Sue Stuart’s home in Lisbon, there is a blood-stained section of rug that’s covered over by a chair.

The blood belonged to her son, Corey Coburn, who coughed it up when he overdosed on the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl and died on that spot in November 2015. Stuart held her son in her arms and screamed for help that never came. He was 28.

She doesn’t have the money to replace the soiled rug. So there it stays, a constant reminder.

Molly Parks died of a heroin overdose April 16, 2015, leaving behind her father Tom, center, sister Kasey, left, and stepmother Pat Noble.

In Saco, Tom Parks has left a pile of boxes in his garage that hold the possessions of his oldest daughter, Molly. She injected a lethal dose of heroin in the bathroom of the restaurant where she worked in April 2015, ending her life at 24.

Parks mourns his daughter every day but can’t bring himself to go through her things. He’s not scared of what he’ll find, just worried that the act might make it easier to move on, to forget, and he doesn’t want to forget.

It’s the same reason he wrote his daughter’s cause of death into her obituary, a disclosure that is still uncommon. He wanted people to know what killed Molly.

In Lebanon, Carly Zysk has battled opioid addiction for years, hoping to spare her parents from mourning the loss of another child.

Her brother, David, had been free of heroin for four years. He had gone back to college and maintained a near-perfect GPA. He had become a leading advocate for the Greater Portland recovery community.

At a candlelight vigil for drug overdose awareness in August 2015, David Zysk spoke about the need for people to stay vigilant in their recovery.

“As much as I hope and pray that the words about to come out of my mouth ring untrue, given the stark facts it is completely possible that not everyone who is here right now will be here a year, a month, or a day from now,” he said.

Zysk’s words were prophetic. A little more than two months later, he died alone after injecting heroin in a South Portland hotel room. He was 33.

“I still think people have this idea in their head about who is caught up in this crisis,” says Dr. Mary Dowd, who specializes in treating addiction and sees hundreds of patients through her work at Catholic Charities Maine, Milestone Foundation and the Cumberland County Jail. “It could be anyone.”

PROMISES OF HELP FAIL TO MATERIALIZE

For Mary Dowd, the main goal is to keep people alive, keep them coming back to see her.

In addition to her work at Catholic Charities, Dowd is the medical director for Milestone Foundation, which runs a 16-bed detox center in Portland. She sees patients at Discovery House in South Portland, where she prescribes Suboxone, a drug used to treat opioid dependence. She also works part-time at the Cumberland County Jail, where addiction drove so many of the inmates’ crimes.

There may be no one who is more connected to the opioid crisis in southern Maine, professionally and emotionally, than Dowd. She has submitted passionate pleas to newspaper op-ed pages, hoping her words might light fires.

“Hasn’t this crisis been in the headlines long enough? Haven’t enough of our children overdosed and died?” she wrote in an August 2015 piece to the Telegram, advocating for better access to Narcan and more funding for treatment.

In another submission from December 2016, she revisited the crisis by looking back at promises that failed to materialize.

“Last year I was hopeful. Things were happening: summits, task forces, community forums, much talk about the opioid crisis in the Legislature, in the news and in towns throughout Maine. I told my patients things were changing, help was on its way,” Dowd wrote. “But for my patients, nothing has changed.”

Not one lawmaker contacted her after that piece ran.

So she keeps going to work, frustrated.

She allowed a Telegram reporter to spend several days with her on the condition that her patients not be identified.

Among the dozen patients Dowd saw that morning in January, the oldest was in his late 50s and the youngest in her early 20s. The majority were in their late 20s or early 30s. Most had children and an underlying mental health problem that led them to use in the first place – anxiety and depression being the most common. Many had a history of substance use in their families.

Their history of use varied, but patterns emerged: They started on a prescription opioid first, often after a surgery or injury. They swore they would never use heroin, until they were using heroin. They swore it was a one-time thing. They tried managing addiction on their own, often by purchasing diverted Suboxone on the street. When they couldn’t find that, they reverted to heroin.

Opioids, perhaps more than any substance, have a profound impact on the brain. Essentially, the drugs take over to the point where the brain can only function when they are present. Getting clean means fixing a brain that has been rewired.

That’s how it has been for Michael Murphy, who agreed to be identified. As of January, he had seven months of sobriety, but it didn’t come easy. He tried many times to get clean on his own but couldn’t do it. It took him a while to ask for help.

Eventually Murphy found his way to Catholic Charities and Dowd, whose clinical approach is compassionate and judgment-free.

“It’s hard to get to that point where you ask for help,” he said. “You think you can manage it and then you just fall back.”

Dowd knows each of their stories, which is remarkable considering she sees hundreds of patients.

She knows that the best way to connect with patients in recovery is to meet them where they are, to understand that relapses are going to happen.

Westbrook native Stephen Barbour, a recovering heroin addict, spends time at a residential treatment facility in Haverhill, Mass., in the spring of 2016. Acting against medical advice, he left the facility just three days later, with hopes of managing his addiction on his own.

THE EVOLUTION FROM PRESCRIPTION PAINKILLERS

The roots of the current opioid crisis were planted in the late 1990s.

At that time, the medical community was under pressure to treat pain more aggressively. Pharmaceutical companies responded. Purdue Pharma, in particular, developed a time-release version of the opioid painkiller OxyContin that was marketed as a wonder drug.

Maine’s fishermen, loggers and other physical laborers provided plenty of demand for the new pain medications, and the prescriptions flowed.

The pill was created to dissolve gradually in stomach acid, releasing the drug slowly into the system over a period of up to 12 hours. But it had a flaw: Enterprising users could crush the pill and snort it, getting the entire dose all at once to produce an instant and powerful high. “Hillbilly heroin” was born.

Kimberly Johnson, who ran the Maine Office of Substance Abuse under two governors from 2000 to 2007, said Maine was the first state to raise the issue of OxyContin nationally.

“For a while, we were voices in the wilderness,” said Johnson, who’s now director of the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment at the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in Rockville, Maryland.

She remembers the first time she encountered a woman hooked on heroin, a powerful and addictive drug made from poppy plants that is often injected directly into the bloodstream.

“It would be what we call a classic case now but you just didn’t see it then,” Johnson said. “She had been in a car accident and was prescribed an opioid for back pain. The prescription stopped but she still had pain.”

Johnson still remembers what the woman told her.

“She said, ‘You’ll think this is crazy but someone told me heroin would take care of that pain,’ ” she said. “And of course it did.”

The shift from prescription painkillers to heroin and now fentanyl can be explained with simple economics.

Yes, the rise in painkiller misuse in the 2000s led to tightening of prescribing practices – a fight that continues today – but high-level drug traffickers also began to flood the market with heroin.

It still found its way to big cities, but from there it started to spread to secondary markets, such as Lawrence or Lowell, Massachusetts, and then to places like Maine. Supply and demand.

VITAL SIGNS: In 2014, Gov. LePage began pushing lawmakers to add agents to the Maine Drug Enforcement Agency in response to the opioid epidemic. In late 2015, money was finally obtained for 10 additional agents. Heroin investigations by MDEA increased from 306 in 2014 to 531 last year, while investigations of other opioid cases decreased from 245 to 155.

Timothy Cheney, a longtime advocate for treatment and a member of the state’s Substance Abuse Services Commission, has studied addiction for a long time and has lived it, too. He was addicted to heroin in the 1970s, before it had spread beyond inner cities.

“To understand an addict, you have to understand their pain. We try to avoid pain,” he said in an interview at his home in Walpole.

It may start as physical pain, but it almost always progresses to suppressing emotional pain, a much more nebulous thing.

“You have to ask yourself, what is happening in this society? We have a breakdown in community, people feeling a sense of disenfranchisement, a sense of dislocation, a sense of not belonging, and in some cases, a sense of no purpose,” Cheney said. “But nobody wakes up and says this is what I want, to be imprisoned by these drugs.”

Cheney, who also is involved with Grace Street Recovery Services, a Lewiston-based treatment center, and founded Chooper’s Guide, an online addiction resource center, joined the state commission because he was tired of seeing inaction.

“The minds that created this problem are not going to be the ones that solve this problem,” he said, paraphrasing Albert Einstein. “And we need new thoughts because, obviously, Maine hasn’t done a very good job in what they are doing.”

Other states are struggling to address the crisis, too, although some have tackled it more aggressively.

CAUGHT IN THE CRISIS: ‘IT COULD REALLY BE ANYONE’

The biggest barrier to meaningful progress remains stigma.

Dowd had a family practice in Yarmouth about a decade ago when she began working part-time at the Cumberland County Jail. She was struck by how much addiction played a role in criminal behavior and decided to practice addiction medicine full time.

In the nearly nine years since, she has learned this: The only thing that separates her from most of the people who sit across her desk every day is circumstance.

“I still think people have this idea in their head about who is caught up in this crisis,” said Dowd, who wears sandals in wintertime and speaks in a warm but no-nonsense manner. “It could really be anyone.”

On that same day in January that she met with patients at Catholic Charities, Dowd checked in during the afternoon at Milestone, the only true detox facility in the state. For opioid users, detox means a gradual weaning off their substance, often with Suboxone, to stabilize them for entry into a more long-term treatment program, either a residential rehab or intensive outpatient program that couples medication with counseling and group sessions.

On that same day in January that she met with patients at Catholic Charities, Dowd checked in during the afternoon at Milestone, the only true detox facility in the state. For opioid users, detox means a gradual weaning off their substance, often with Suboxone, to stabilize them for entry into a more long-term treatment program, either a residential rehab or intensive outpatient program that couples medication with counseling and group sessions.

Dowd does medical intakes on every patient who comes through Milestone. There are 16 beds there, but patients typically spend only five to seven days. Some don’t make it that long. The facility turns away dozens every week because it doesn’t have room.

Those who do secure a spot are often desperate. Like her Suboxone patients, their stories have similarities. Many have tried to stop before, and some even had long periods of clean time before relapsing. With each relapse, the addiction worsened.

Dennis, 33, told Dowd he’s been using anywhere from 1 to 2 grams of heroin a day. He started about six years ago, after a shoulder surgery for which the doctor prescribed Vicodin. He didn’t know he was dependent until the prescription expired.

He had some legal trouble related to his drug use early on and ended up in jail. After he got out, he was drug-free and stayed that way for three years.

“But time passes,” he said. “You forget. You stop working on your recovery.”

Pills turned into heroin simply because that’s what he could afford.

At that point, Dowd asked him what she asks every patient during an intake: Why did you decide to come in?

“I’m just sick of fighting every day,” he said, his voice weary. “It’s like I’m leading a double life. I work all day and then I’m a drug addict at night. I’m just tired.”

She asked him what he planned to do after detox. He told her he got accepted into Milestone’s residential program in Old Orchard Beach. It’s a lengthy program – nine months or more – but he’s ready. And grateful. The program keeps open just three scholarship beds for people who can’t pay and, if Dennis can hold it together, one of them is his.

When he left, Dowd said she was glad he had found a treatment bed. Most patients aren’t that lucky, especially if they don’t have MaineCare or private insurance. Most facilities don’t have scholarship beds.

Jennifer Ouellette, clinical director of York County Shelter Programs, has seen the opioid crisis move in slowly but she still remembers her first client who died.

“I remember feeling so sad because he had no family support,” she said. “And all the things people value when it comes to death – I remember thinking who’s going to do that for this guy? And then I started thinking about this guy as a child. It really had a profound effect on me.”

So, she started keeping a list of people who died.

“I kept that list for years until it got to be over 100. Then I had to stop. It just got to be so painful.”

Sometimes you wonder if you make a difference, she said, and then you get a card or a phone call out of the blue and it’s someone who is doing well.

“But I see no human compassion at all sometimes. I see people say, ‘You’re choosing to use,’ but you’re missing about 30 chapters before that needle goes in the arm,” she said. “No one starts there.”

BOLD RESPONSES IN VERMONT, MARYLAND

As many states grapple with their own crises, nearby Vermont offers a sharp contrast to Maine in its response.

In 2014, Gov. Peter Shumlin, a Democrat, devoted his entire State of the State speech to the opioid crisis, focusing particularly on increasing access to treatment, on treating addiction as a public health issue rather than as a crime, and on compassion.

Gov. Peter Shumlin in 2014 proposed a $6.7 million plan to create a coordinated system for treatment and recovery in Vermont. The number of overdoses in the state remained largely unchanged from 2011 to 2015 before rising in 2016.

Within a few months, Shumlin had proposed a $6.7 million plan to create a coordinated system for treatment and recovery that is referred to as the “hub and spoke” model.

By 2015, the number of people enrolled in a methadone program had tripled.

The number of overdoses hovered between 97 and 108 a year from 2011 through 2015, before rising to 155 in 2016.

Vermont also instituted a program that steers low-level lawbreakers with drug addictions into treatment and other services, bypassing jail but using the threat of prosecution as leverage. Operating entirely outside of a courtroom, prosecutors in participating counties can allow people arrested on drug charges to move on with no charges if they adhere to a contract.

That type of intervention has happened in small pockets of Maine. The Scarborough Police Department’s Operation HOPE is a good example. But there is no state support and Operation HOPE is in danger of folding.

Just this month, Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan declared a state of emergency and proposed spending an additional $50 million over the next five years to battle his state’s crisis. Maryland officials believe the high death toll more than justifies the declaration, which they hope will help break down silos within government that have impeded meaningful progress.

Here in Maine, the LePage administration’s response to the drug crisis, until recently, was heavily weighted toward increased law enforcement.

In his own State of the State address in 2014, LePage spent much of his time talking about the policy goals that have defined his administration: tax cuts, bloated government and welfare reform.

He mentioned the drug crisis at the end but focused on drug-affected babies and how that would further strain the welfare system.

LePage then mentioned traffickers and said the state needed more drug agents. He never used the word “treatment.”

In the summer of 2015, after a particularly deadly two-week stretch, LePage announced a summit to address the crisis. But again, he focused on law enforcement and said that there was plenty of treatment available. In a note to Rep. Mark Eves of North Berwick, who was then speaker of the Maine House of Representatives, the governor wrote: “2014 – $72 million spent on Rehab. – Demand Addressed/Supply Growing,” before signing his name.

In the last few months, the LePage administration has committed to $5.5 million in new spending for medication-assisted treatment, both for the uninsured and for those enrolled in MaineCare. It’s not clear why the state changed its approach.

Experts who have studied the epidemic for years have concluded that the investment in treatment has the biggest payoff. The return for every $1 spent on treatment is $4 to $5 saved on health care and as much as $7 on law enforcement, according to estimates by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

In addition to relatively flat funding of treatment, it was only last year that lawmakers overrode a LePage veto to provide funds for needle exchanges, and little state money has been committed for Narcan – both of which are proven to reduce harm and save lives.

‘WE’RE JUST NOT GETTING AHEAD OF IT’

Maybe the solutions are simpler than massive line items in a state budget.

Some think every physician in Maine should apply for a federal waiver that allows them to prescribe Suboxone. Soon, thanks to relaxed federal regulations, nurse practitioners and physician’s assistants will be able to apply as well.

Rep. Ellie Espling, R-New Gloucester, submitted a letter to House Speaker Sara Gideon, D-Freeport, and Senate President Mike Thibodeau, R-Winterport, asking them to convene a joint select committee to work solely on Maine’s drug crisis.

Ouellette, with York County Shelter Programs, said maybe organizations can offer more free care.

“Maybe you do a bottle drive or maybe you don’t buy new office furniture for a couple years. If everyone did this …” she said before snapping back to reality. “But I think everyone is kind of doing their thing, which is to try and survive, to keep the lights on and to keep their clients alive. That’s no way to operate.”

Rep. Eleanor Espling, a Republican House leader from New Gloucester, late last year proposed a joint special committee devoted solely to the crisis. The idea didn’t get much traction and instead was effectively replaced by yet another task force. LePage, during his State of the State address in January, declared “everything is on the table” when it comes to battling the crisis and, so far, his administration has committed more resources.

Ouellette, the Brunswick psychiatrist who lost her son more than three years ago, said she worries that a lack of consensus will lead to inaction. She doesn’t want other parents to feel what she lives with every day.

“We’re trying to address this as the problem is growing, and it’s growing at a much faster pace than we’re addressing it,” she said. “We’re just not getting ahead of it.”

That’s how it feels for Dowd, too. Two weeks after that morning in January, she was back at Catholic Charities, seeing some of the same patients as before.

Tanya, the 34-year-old mother of three who is trying to buy a house in Buxton, returned. She and Dowd talked about the previous 14 days.

Tanya said she had watched the HBO documentary “Intervention,” about addiction.

“It was sad because it reminded me of how I used to be,” she said. “But I feel so far from that.”

Tanya has four years under her belt. She’s proud of that. She’s still on Suboxone. She sees Dowd twice a month and does additional counseling once a month.

She works a lot. She wants to go back to school.

“Work is fine but I want a career,” she said.

Another young woman, Jessica, came in next. The nurse had warned Dowd that she believed Jessica was using again. She was fidgety. Her handwriting compared to the previous session was messier.

When Dowd asked her, Jessica just shook her head.

Her answers were short.

Dowd tried one last time to break through.

“You know, if you relapse, we’ll still work with you,” she told her. “It’s always better to be honest.”

The woman walked out, prescription in hand.

Dowd sighed and turned back to the list to see who was next.

This story was updated at 4:09 p.m. April 13, 2017 after the Maine Attorney General’s Office revised its preliminary estimate of the number of drug overdose deaths in 2016.

Staff writers Mike Lowe and Steve Craig contributed reporting for this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.