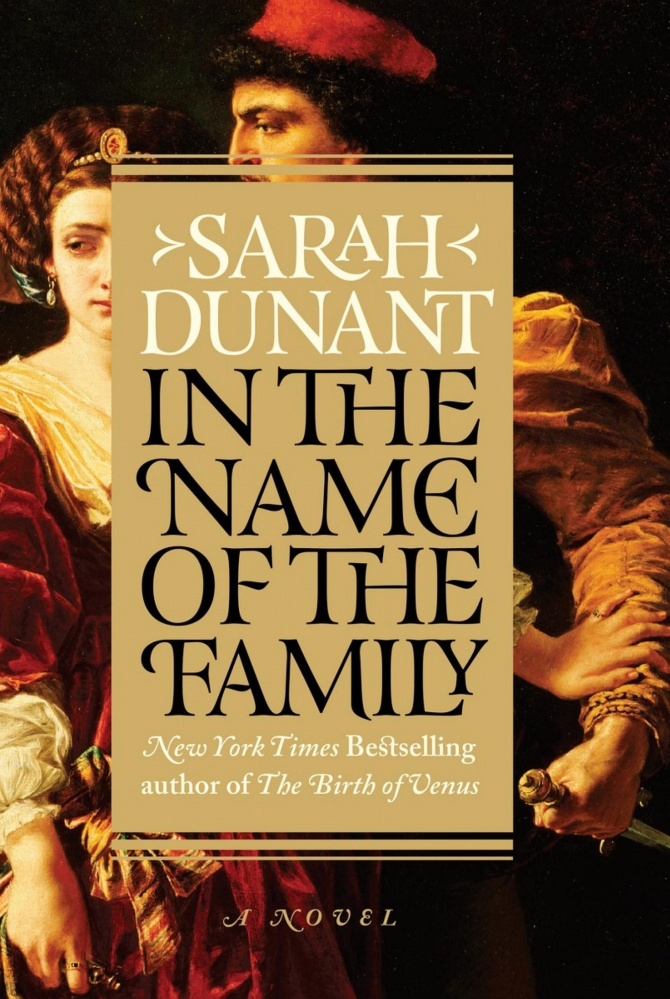

“Poison” is probably the first word that springs to mind when you hear the name Borgia. Followed rapidly by “incest,” “murder” and “plots.” Borgia is a historical name with a lot of resonance. So, for that matter, is Machiavelli. So imagine the history of the Borgias as witnessed by Machiavelli. That’s the irresistible combination in Sarah Dunant’s new novel, “In the Name of the Family.”

Late-15th-century Italy is fascinating: a sprawling crazy-quilt of powerful city-states, each with a ruling family. The Vatican – improbably – was one such city. The Borgias originated from Valencia and infiltrated Italy via the church. Dunant’s novel explores the lives of the three most infamous figures during the height of their ambition: Rodrigo, Pope Alexander VI; his daughter Lucrezia; and his son Cesare.

The outward story here is the attempt by the family to create their own Borgia state by conquering a string of the most important city-states and subduing them under Borgia rule.

Alexander, an expansive, charming, clever man of huge appetite, contributes the money, the political connections and the not-inconsiderable power of the papacy itself. (If you hold the power to excommunicate believers, they’re much more likely to do what you want.)

Cesare, an archbishop and then a cardinal in his teens (add “nepotism” and “bribery” to the Borgian taxonomy), leaves religion behind (in all ways) and raises his own army with which he sets out on a campaign of blood and terror, his father’s war-chest footing the bill.

Meanwhile, Lucrezia, beautiful, charming, twice-widowed and just as clever as her male relatives, is obliged to leave her small son to make a dynastic marriage with the son of the Duke of Ferrara, making Ferrara one city her brother doesn’t have to take by force. She finds a way for her spirit to survive even as she helps her family prosper.

But despite their very public lives, each of these characters has an inner story, too, and Dunant does a terrific job of showing us what makes them tick – both directly and through the eyes of Machiavelli, then an apparatchik for the city of Florence, sent to witness Cesare’s march across Italy. All in all, they’re a magnetic bunch, these Borgias. Often we’re shocked by their ruthlessness, but just as often they elicit our admiration and sympathy. These people and their times are drawn so well that we understand both on a visceral level.

Beyond the attraction of the characters and the history, Dunant has a great immersive style. Her hallmark is the penetrating detail, such as Alexander’s fondness for marinated anchovies and the “fishy burps” that result; the corners of a war chart hastily stuck on a wall, grease seeping through the paper. Death is raw and ghastly, bloody bones butchered in snow. Marital sex in the dark is fleshy and slippery, and Lucrezia’s husband makes terrible noises in bed.

The most important detail is a silent presence that winds its grisly way through the story: the French pox, fulminant syphilis. Sometimes dormant, sometimes virulent, it makes its own mark on history, maiming soldiers and politicians, whores and princes, killing children in the womb, its nature unbeknown to its victims.

In the end, what’s a historical novelist’s obligation to the dead? Accuracy? Empathy? Justice? Or is it only to make them live again? Dunant pays these debts with a passion that makes me want to go straight out and read all her other books.

Send questions/comments to the editors.