WATERVILLE — On a bright but cold Thursday morning, Michael Libby stood in Thomas College’s Ayotte Auditorium, where a week earlier his artwork had brought the community together for a discussion on drug addiction.

Libby, 57, a Waterville native who lives in Lewiston, is an artist as well as a certified alcohol and drug counselor, and this spring he expects to graduate from the University of Southern Maine with a master’s degree in psychiatric rehabilitation counseling.

In Ayotte Auditorium, he stood before a section of an exhibit he has shown a handful of times in Portland and Lewiston. The exhibit at Thomas – which was taken down Thursday – is about addiction; but as Libby describes it, it is also about personal loss.

“Art has a way of objectifying ideas,” he said.

And art can provoke strong public response. Libby plans to take his art to an even higher level, literally, with a 30-foot-tall hot air balloon shaped like the chemical compound of heroin.

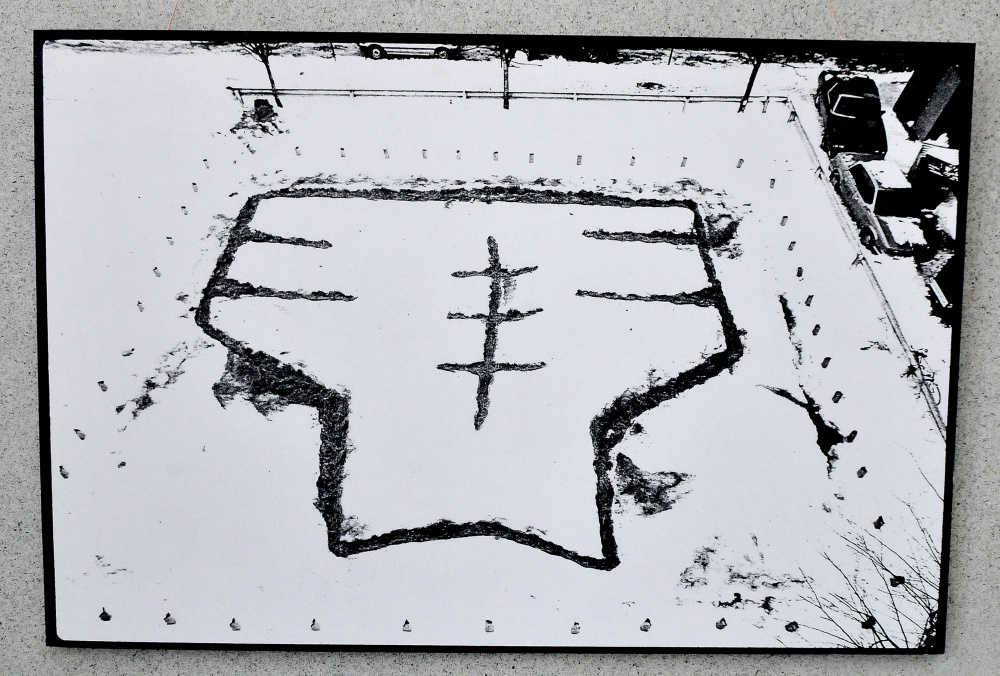

Over the course of 20 years, Libby lost three of his four siblings to drug- or alcohol-related deaths. His brother Reno died of a heroin overdose in 1992. It was after that when Libby began walking in Portland parking lots. Eventually he began sketching them. Later, he put the lots onto canvas, painting abstract images of bird’s-eye views of the areas he walked.

“Part of my motivation is to learn about myself,” Libby said, “but the show is also about saying goodbye and welcoming grief.”

The Thomas display contained about a third of his entire exhibit, Libby said, with two parking lot images and a quilt he had made in 2013. In describing the quilt, Libby addressed what he saw as the real issue with addiction. Especially with the opioid epidemic in the state, he said, the real issue is a desire on the part of the user to solve an issue of alienation.

“Heroin isn’t killing people; loneliness is,” Libby said.

Libby’s quilt is titled “Opium: A Comforter” – comfort is one of the things someone is looking for when they turn to opioids, he said. He said heroin creates a chemical sensation of love.

Part of the work in creating the art was a desire to understand those feelings of alienation better and to try to find an answer for it. He said some kind of support needs to be provided to replace the chemical feelings of love and comfort created by heroin.

“We can all relate to loneliness,” he said.

MAKING CONNECTIONS

Libby said he wants to continue exhibiting his work, and hopes to do a five-mill-town tour, with stops between Biddeford and Bangor.

Libby said he wants to bring the exhibit to mill towns both because he’s from Waterville – where several manufacturing businesses have closed in recent decades – and because it seems like mill towns are hit harder by heroin addiction.

Mainers are dying in record numbers because of drug overdoses, with 378 fatalities in 2016, a 40 percent increase over the 272 in 2015.

Libby said he has spoken with Waterville’s arts commission about a public display, but any future plans would depend on securing funding.

Libby said he wouldn’t want to set up a permanent location for his art, and he wouldn’t consider selling it. That’s because he considers the art more of a backdrop, a way to get people into a room and begin a community dialogue about the issues behind the art.

“Connecting with an audience and the public is really the motivation for the art,” he said.

Colin Ellis can be contacted at 861-9253 or at:

cellis@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @colinoellis

Send questions/comments to the editors.