Guy Linscott longs for how it used to be in South Portland.

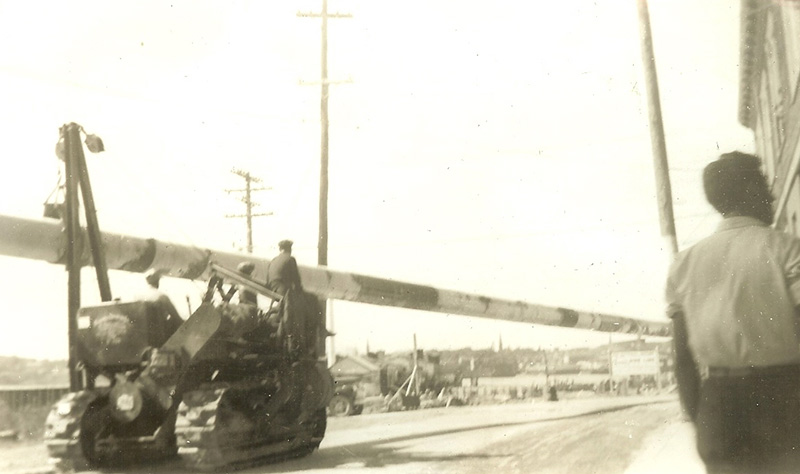

Back when the nation was on the threshold of World War II, and city residents watched with pride as an oil pipeline was laid from the edge of Portland Harbor, through residential neighborhoods and past schools, on its way to refineries in Montreal.

The 236-mile pipeline was completed in less than five months in 1941, with little protest and the full backing of the City Council, Gov. Sumner Sewall and President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Land was purchased and taken, homes and other buildings were demolished, and streets were torn up from Ferry Village, across the city and beyond. By November, the pipeline was fueling Canada’s contribution to the British fight against Hitler’s Nazi regime.

South Portland’s pride grew after the United States entered the war and shipyards flanking the pipeline churned out Liberty ships in a jaw-dropping industrial enterprise that employed 30,000 people at its peak, a workforce nearly double the city’s population at the time.

“There were many jobs back in those days,” says Linscott, his tone a bit mournful. “It was all hustle and bustle. We had government projects all over the place to bring people into the area. People got along with each other and business got along with people. They lived side by side and they worked side by side. There were never the issues that we’re facing today.”

Guy Linscott, who raised a family in Ferry Village, is concerned about South Portland’s growing tax burden. Linscott says he’s frustrated that city officials didn’t seem affected by Gov. Paul LePage’s move to strip South Portland’s business-friendly designation in 2015. Staff photo by Ben McCanna

The South Portland that Linscott sees now, he says, is increasingly anti-industry, liberal and intolerant of people like him, a 79-year-old conservative Republican who voted for Donald Trump and doesn’t like the progressive agenda that’s been pushed for several years by a left-leaning City Council and the Protect South Portland advocacy group.

In a little more than a decade, South Portland has moved away from its roots as a mostly working-class, industrial city to become an outwardly progressive, pro-environment mecca where people with conservative views say they feel silenced, even ostracized. The city’s more liberal residents, meanwhile, make no apologies for adopting new priorities, such as promoting solar energy and climate awareness, welcoming immigrants and other minorities, banning plastic shopping bags and pesticides, and fighting petroleum interests that once operated unfettered in the city, including the pipeline company.

Like Portland across the harbor, South Portland has attracted retirees, artists, entrepreneurs, immigrants and other newcomers who have changed the city in measurable ways. Its 25,300 residents are, overall, more highly educated, professionally employed and racially diverse than ever before. And while its politics continue to be solidly Democratic, with South Portlanders backing Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump by a more than 2-to-1 margin, the city has grown increasingly focused on environmental and social justice issues.

City officials have taken some heat for their decisions, mostly in the form of comments on social media and online news stories, where critics chastise them for their liberal policies and call them anti-business and anti-worker. They vehemently reject the labels and point to a thriving commercial tax base and strong business development of all kinds.

The intensity of partisan discord in the city became apparent in 2015, when a community controversy drew national attention. South Portland High School students had informed their peers that they weren’t legally required to recite the Pledge of Allegiance each morning.

The public reaction had surprising racial overtones. Although the effort was led by three white, top-ranked, native-born students, a popular Facebook post by a prominent local businessman spread the idea that they were children of immigrants who didn’t pay taxes and didn’t want to say the pledge. School and city leaders backed the students, but hard feelings remain.

The widening gap between left and right in South Portland reflects U.S. political divisions. The simmering conflict has set neighbor against neighbor, forced some prominent city officials to temper or conceal conservative leanings, and made dinner chat difficult for some families. It has stifled conversations between Guy Linscott and his daughter Brenda Peluso, a 55-year-old liberal Democrat who generally supports the City Council’s progressive agenda.

“It’s hard for us to communicate because it seems like we’re not even talking about the same things,” Peluso says of political discussions with her father. “We’re not even using the same language.”

POWERFUL PARTISAN DIVIDE

Nothing reflects or has intensified the hard feelings in South Portland more than the fight over the future of the oil pipeline and its 23 massive storage tanks that now lie mostly dormant through the heart of the city.

The City Council passed what is known locally as the Clear Skies ordinance in 2014, with the goal of blocking the Portland Pipe Line Corp. from potentially reversing its flow and bringing controversial tar sands oil from Canada to be loaded on ships bound for markets around the world.

Portland Pipe Line Corp. oil tanks near Sawyer and Front streets in South Portland. A World War II-era pipeline that once carried oil from Portland Harbor to Canadian refineries is a flashpoint in the debate over the city’s commitment to industry vs. environmentalism. Councilors passed an ordinance in 2014 meant to keep the pipeline from being used as a means of bringing in tar sands oil from Canada. Now 23 storage tanks lie mostly dormant throughout the city.

Declining demand in Canada for foreign crude has slowed tanker deliveries to South Portland’s waterfront to fewer than a dozen last year, mostly to keep the pipeline wet. Meanwhile, Canada is now refining heavy crude from its western provinces and North Dakota.

The pipeline company, a Canadian-owned subsidiary of ExxonMobil and Suncor Energy, is challenging the Clear Skies ordinance in federal court, and the city has racked up more than $1 million in legal fees defending it so far.

More recently, the company has applied for a property tax abatement, blaming the ordinance for a 42 percent reduction in the $44.7 million assessed value of its holdings across the city. If the city assessor granted the abatement as requested, the company’s annual tax bill would drop from $791,447 to $460,200.

As the costly legal battle plays out, some view it as a shameful effort to shut down an enduring and still relevant reminder of South Portland’s patriotic commitment to freedom, industry and jobs during World War II. Others see it as a valiant fight against “Big Oil” and a necessary campaign to heal an unsightly gash in the city’s landscape and bring an end to the 75-year-old remnant of its contribution to the war effort.

Members of the latter group question the local benefit of the pipeline company as a taxpayer, employer and economic driver relative to its 210-acre, heavy-industrial footprint. They believe the pipeline’s properties, including prime waterfront and wooded parcels, would be better used for much-needed housing and more environmentally friendly businesses that could generate more property taxes and employ more people. While the pipeline was reported to have about 40 employees a few years ago, it’s unclear how many of them worked in South Portland, and the company declined to discuss its current operations.

TIMES CHANGE, VALUES CHANGE

Supporters of the Clear Skies ordinance and other progressive municipal efforts are unapologetic for taking a different tack in the face of changing times.

“I’m proud of it,” says Tom Blake, former mayor and longtime city councilor who termed out of office in December. “Our community is attracting people with liberal ideas. The people who disagree with us represent 30 percent of the voters, at max. People rarely get up and speak against what we’re doing. I listened to them, but I think they are wrong. We can’t control what has transpired. You can’t go back in time. A lot of this is just progress.”

Former South Portland Mayor Tom Blake, who grew up in Pleasantdale, with his grandchildren, from top, Solaya Blake-Sainthelmy, 5; her twin, Giselle; and brother Zenon, 3. Blake says he’s seen the city move away from its more blue-collar, industrial roots, but he thinks it’s in step with its residents.

Blake, 65, raised a family on High Street in Ferry Village. The pipeline runs right by his house, about 4 feet beneath the pavement. He grew up on Chestnut Street, in the Pleasantdale neighborhood, beside one of several tank farms in the city. As a boy, he looked out his bedroom window at a massive Texaco fuel tank that served as a backdrop for pickup baseball games and a platform for jumping into snow piles.

“There was no negativity toward business back then,” Blake says. “I don’t remember anybody ever criticizing any of that.”

But times change, says Blake, a retired firefighter who teaches state history at Southern Maine Community College. When he attended Mahoney Junior High School in the 1960s, he brought a gun to school for weekly rifle club meetings, something that wouldn’t be tolerated today.

Blake says he never met a black person or witnessed a political protest until he left Maine in 1970 to attend college in Connecticut. Now, six of his 14 grandchildren are biracial, and three of them live right around the corner. When he joined the South Portland Fire Department in 1980, there were no women on the City Council.

But perhaps most telling of all, Blake says, no zoning review or environmental impact study was done before the pipeline was laid along busy streets and through residential neighborhoods of South Portland. Or when the tank farm was built on Hill Street in the center of the city, on former farmland bounded by three elementary schools.

When 200 safety-minded residents protested against the tank farm in 1941, the City Council unanimously approved construction of the first four tanks, according to a Portland Press Herald report from July of that year. When the council approved a tank farm expansion in 1948, more than 300 residents petitioned for a citywide referendum to stop it. Voters approved the expansion by a 2-to-1 margin, with proponents calling it “a progressive move toward industrial growth in South Portland.”

Blake happily predicts that neither city officials nor voters would make the same decisions today.

“Those who long for the good old days in South Portland are outnumbered,” Blake says. “Just because they don’t like what’s happening doesn’t mean it’s wrong.”

NEWCOMERS BRING CHANGE

Nancy Smith at home on Ardsley Avenue in South Portland: “I’m so glad my children are in a diverse classroom. I want them to be able to embrace and understand different perspectives.”

Nancy Smith is one of the newcomers to South Portland, and one who appreciates how the city is evolving. A psychologist and divorced mother of two school-age children, Smith moved here four years ago and bought a house on Ardsley Avenue, in the Thornton Heights neighborhood.

She notes that she lives on the west side of South Portland, near Route 1 and the Maine Mall area. It’s more racially, ethnically and socioeconomically diverse than the east side, which is near the waterfront and Cape Elizabeth. Her kids attend the Skillin Elementary and Memorial Middle schools.

“It was the community that had everything I was looking for,” Smith says of South Portland. “Convenience. Good schools. Things are very different on the west side, but I’m so glad my children are in a diverse classroom. I want them to be able to embrace and understand different perspectives.”

A Philadelphia native who moved to Maine when she was 12, Smith sees how South Portland has changed in other concrete ways. Housing costs are skyrocketing and businesses are flourishing, especially on the east side. The city is paying more attention to the west side, dressing up Main Street and making other infrastructure improvements. And she sees how its people and its politics have evolved.

“It used to be viewed as more blue-collar, and it’s definitely moving in the direction of being more progressive,” says Smith, 47. “I think it reflects the new face of South Portland. But I don’t think it’s easy for a city to shed the narrative of its history. I can understand why there would be a lot of discussion about the direction it’s going.”

What’s happening in South Portland is apparent in U.S. Census data that show the city’s demographics have changed in notable ways over the last 25 years.

Its residents are significantly more educated. The number of adults age 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree or higher has nearly doubled, from 21.4 percent in 1990 to 41.7 percent in 2015. The segment of adults who work in management and other professional jobs increased more than 60 percent, from 26.2 percent to 42 percent.

South Portland has grown more racially diverse, though it’s still mostly white – 94 percent, down from 98.6 percent in 1990. The black population increased from 0.3 percent in 1990 to 2.5 percent in 2015, in part because of recent African immigrants. The Asian population, including many Vietnamese residents, increased from 0.7 percent to 4.9 percent. And the Hispanic population grew from 0.9 percent to 1.9 percent. Percentages for minority populations in 2015 reflect people who reported more than one race.

Meanwhile, the city’s foreign-born population grew from 4 percent to 6.9 percent, surpassing the current state average of 3.5 percent, and the population that speaks a language other than English grew from 5 percent to 8.9 percent, compared with 6.6 percent statewide today.

EXPLOSION OF DIVERSITY

School Superintendent Ken Kunin addressed the growing diversity in the city’s schools in January, during his State of the Schools presentation to the City Council and the School Board.

Kunin noted that 271 or 8.9 percent of the district’s 3,032 students now receive additional services because they are learning to speak English. They are concentrated on the west side of the city, where housing is less expensive, attending Skillin and Kaler elementary schools and Memorial Middle School. They speak 32 different languages at home, with Arabic, Spanish, French, Somali and Vietnamese being the most common. In 2005-06, the district had 88 students who were learning to speak English – about 3 percent of the student population – and they spoke 22 languages at home.

The increase prompted Kunin to send a letter to the school community in January, after President Trump signed an executive order banning immigrants and refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries. Kunin was concerned that the order would make some students feel unwelcome.

“Again, we say clearly and loudly that you are welcome in our schools,” Kunin wrote. “We want to leave no doubt where we stand. We are the sons, daughters and grandchildren of immigrants. We respect our heritage and we value the futures being created by all of our families, whether they come from around the corner or across the globe.”

The City Council went a step further, passing a resolution in February that expressed support for Muslims and immigrants and condemned hateful rhetoric, especially by elected leaders. No one spoke against the measure and more than 20 community members voiced their support, including Aysha Sheikh, who lives on Fairlawn Avenue and works as director of programs at the Maine Cancer Foundation.

“My father is an immigrant from Pakistan and more than half of my family continues to live there,” Sheikh said to the council. “It matters a lot to me that when my father or other family members visit me and my family in South Portland, they feel supported, safe and accepted, and up until recently, we always have. I appreciate that.”

But some city residents question the need for the resolution, including Mike Pock, a former city councilor who is a Republican and a self-proclaimed Tea Party activist. Pock believes that the resolution was an unnecessary overstep because the executive order didn’t specifically name Muslims as its target.

“Why did the City Council have to come out with this?” says Pock, 70, a semiretired handyman who has lived in South Portland since 1973. “It doesn’t mean anything. They’re just playing to their liberal, progressive base.”

Pock was the lone city councilor who voted against the Clear Skies ordinance in 2014, and he was one of four at-large council candidates last fall who said they didn’t like or would try to overturn the decision. Those candidates, all of them men, also opposed the pesticide ban. All of them lost. Pock came in last.

“I’m against the city telling business what they can and can’t do,” Pock says. “They’re discouraging business in this town.”

The two open at-large council seats that Pock and the other men sought were won by two liberal candidates, Maxine Beecher and Susan Henderson, both women in their 70s.

“The more conservative candidates got spanked,” says Blake, the former mayor and councilor. “Those who are stuck in the old ways are falling behind. They can’t win at the polls and they can’t win at City Hall.”

WRESTLING WITH THE CHANGES

Guy Linscott is well aware that his views are now in the minority at City Hall and in the community as a whole. A retired pharmaceutical salesman and a Navy and Coast Guard veteran, Linscott grew up in South Portland and raised a family here. Now, he lives on North Marriner Street, a few houses away from Tom Blake.

Linscott says he’s concerned about the influx of immigrants and other newcomers, as well as the growing tax burden, the lack of good jobs and the absence of a strong work ethic among the younger generations.

But it’s the fight over the oil pipeline, which runs beside Linscott’s tidy white ranch, that makes him feel like an outcast. He commiserates with like-minded friends who meet for coffee most mornings at the Dunkin’ Donuts in Mill Creek.

Students walk down Elm Street in South Portland’s Pleasantdale neighborhood, near the Irving-Citgo terminal that includes 10 of the many fuel-storage tanks scattered across the city.

“The political picture here has changed almost 100 percent from when I was a young man,” Linscott says. “Our city right now is so divided that neighbors aren’t talking to neighbors anymore, because they know what their stance is. We have a political air in the city that is frightening, to be honest with you, because it’s leaning towards one way and one way only, and if you’re not on that bandwagon, too bad, you don’t have a say.”

Linscott especially resents the council’s passage of the Clear Skies ordinance after city voters narrowly rejected a similar measure, called the Waterfront Protection Ordinance, in a 2013 referendum. Though supporters see the Clear Skies ordinance as carefully tailored and different from its forerunner, its purpose was largely the same.

It also irks Linscott that city officials were unfazed when Republican Gov. Paul LePage’s administration stripped South Portland of its business-friendly designation in 2015. Granted in 2013 through a program established by LePage, the mostly ceremonial honor was yanked after the council passed the Clear Skies ordinance. A spokesman said the administration was “very disappointed” that South Portland would “pass an ordinance that is clearly anti-business, anti-growth and anti-jobs.”

Linscott and others see a negative trend in the way the council and other city officials respond to public pressure to scrutinize and control business activities in South Portland, especially petroleum companies. In addition to the Clear Skies ordinance, the council narrowly passed a controversial fire code amendment in 2016 that killed a proposal for a $3 million propane depot on the railroad at Rigby Yard.

“To see what they’re doing to companies that try to come into the city now, it’s just crazy,” Linscott says. “There’s a movement to keep industry out of here. They want to turn this (city) into a Camden or a Rockport or a Kennebunkport. And they’re driving the Portland Pipe Line out. They say if it goes, they can put homes in the area where the oil tanks are. Yeah, you can, but it’s going to take years to do that.”

Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Twitter: KelleyBouchard

Send questions/comments to the editors.