Julie Voisine clutches the red-and-white cane in her hand and listens to the Congress Street traffic whiz past her.

“Can you get us back to the car?” Mike Dionne asks.

“Probably not,” Voisine replies.

“Break it down,” Dionne says. “You got it.”

“Says the man who can see,” Voisine says.

She gives him a sarcastic smirk, but she starts to walk.

Now 53, Voisine has been legally blind since age 28. She has retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited eye disease that has slowly claimed her peripheral vision. She also has developed macular degeneration, which is causing her to lose her central vision. Although her sight has always been limited, it has shrunk to a pinprick in recent years.

“I have one spot in my vision,” Voisine said. “It’s like taking a straw and putting it up to your eye and looking out of it and crimping the end of it.”

In January, Voisine enrolled at the Iris Network Rehabilitation Center in Portland. The 12-week residential program teaches skills she will need to live and work independently when she has entirely lost her vision. Dionne, an orientation and mobility specialist, is one of the instructors who has been working with her for weeks.

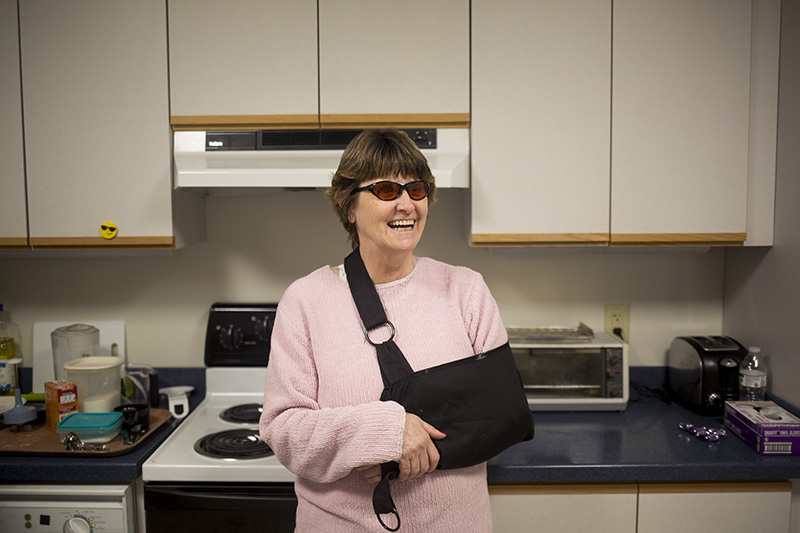

Earlier in the week, Voisine slipped on a patch of ice during a solo trip to the post office. Her arm is in a sling during her lesson with Dionne on a sunny Thursday in February, but she sets out with her cane anyway.

“There’s too many other things trying to stop me,” Voisine said. “My vision isn’t going to be one of them.”

‘BOOT CAMP FOR THE BLIND’

The Maine Institution for the Blind formed in 1905. Its founder was a visually impaired traveling almanac salesman who wanted to help other people with vision loss earn a living wage and learn a trade. The nonprofit has changed its name over the years, but Director of Program Services Rabih Dow said the Iris Network still has the same goal.

“People come to us and say, ‘What jobs can blind people do?’ ” Dow said. “We say, ‘What job would you like to do?’ ”

The 2015 National Health Interview Survey estimated that 23.7 million American adults – about 10 percent of Americans 18 years and older – reported they have some level of vision impairment. That group includes a range, from people who have trouble seeing even while wearing contacts or glasses to those who are completely blind. Most are born with sight and lose it either through disease or trauma, Dow said.

“The stereotype of blindness is very stark,” he said. “It is a relatively uncommon disability, so it can be very isolating.”

In 2015, the Iris Network added its first live-in program. Over three months, clients live in a dorm setting in Portland’s Parkside neighborhood and study a range of subjects.

“Think of it as a boot camp for the blind,” Dow said.

Growing up in Penobscot County, Voisine has always known she would lose her vision. Many of her family members – her mother, six of her eight siblings, her son – also have retinis pigmentosa.

As an adult, she ran several small businesses over the years with her husband. Before he died nine years ago, they had owned a garage, a redemption center and a karaoke service together. But as her vision has worsened, Voisine has not been able to work at all.

Limited public transportation near her home in rural Kingman has frustrated her. She likes to travel, but she relies on her friends to drive her to appointments and the grocery store. She loves to bake, but she began burning or cutting her hands in the kitchen. She missed reading, but she abandoned two attempts to learn Braille.

When a counselor told her about the Iris Network Rehabilitation Center, Voisine signed up immediately.

“This program for me is about freedom,” she said. “It’s being free to do the things I want to do.”

LEARNING TRICKS OF INDEPENDENCE

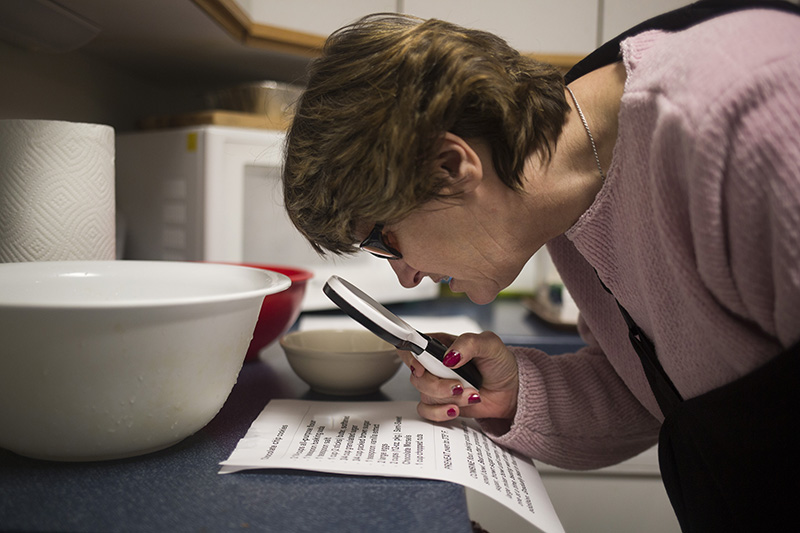

Voisine bends over a list of ingredients with her magnifying glass.

In a practice apartment at the Iris Network, clients learn how to cook, do laundry and manage their homes without their vision. So far, Voisine has made red velvet truffles and cheesecake in the test kitchen. Today, she considers two copies of the same recipe for chocolate chip cookies – one in large print, one in Braille.

“I had to give away a lot of my recipe books before I came here,” she said.

With her arm in a sling, Voisine needs some help whisking from Karen McKenna, a certified vision rehabilitation therapist. But she still finds the butter in the refrigerator and preheats the oven. McKenna has labeled many of the spices and measuring cups in the kitchen with Braille.

She and Voisine review the tips she has learned in the kitchen. They place all the necessary ingredients on a tray to keep them organized. Voisine knows to feel the edges of the broken eggshell with a finger to identify the size and shape of any missing chunks. McKenna teaches her students how to identify the sounds and smells that mean food is done cooking.

“Hey, Siri, set a timer for nine minutes,” Voisine instructs her phone.

The practice apartment is just one of the classrooms that Voisine visits each week.

Elsewhere, she is finally getting the hang of Braille. In the low-vision clinic, clients learn how to maximize the sight they still have. For Voisine, this involves tools like glasses to reduce glare and talking apps on her cellphone. The program puts an emphasis on learning to use the computer to pay bills, file taxes, keep up with an address book and manage other daily tasks. All clients participate in individual and peer counseling. Voisine is making a toy workbench for her grandson in a woodworking class. Her orientation and mobility class takes her outside in all weather to find her way through the grocery store, the public bus system and the streets of Portland.

“I am not my cane,” Voisine said. “I am just somebody trying to live my life.”

The smell of warm cookies fills the kitchen. Voisine sniffs the air.

“The cookies are almost done,” she says.

She opens the oven just as the timer buzzes.

FROM CAUTIOUS TO CONFIDENT

When Voisine graduates from the Iris Network program, she hopes to find work in Portland.

She has joined the YMCA and applied for an apartment. She often helps the staff at the nursing home where her mother lives, so she has decided to become a certified nursing assistant. She would also like to find a part-time job at a bakery.

She will take the bus from Portland to New York City to visit her son this spring, and she wants to travel to England and Ireland next year.

“I’ve had people say to me, ‘I’d rather be dead than blind,’ ” she said. “I’m like, ‘I’m sorry your life is so small.’ ”

When she first started to walk the streets of Portland with Dionne, Voisine was cautious and slow. She often wears a blindfold during these lessons to prepare for her total vision loss, and the traffic in Portland is busier than her hometown. But her confidence has grown with every lesson.

“She’s embraced it,” Dionne said. “She goes out and does the things she wants.”

During their recent lesson, she walks Congress Street in the afternoon sun. Dionne follows a few paces behind, ready to intervene when she gets turned around in a parking lot. He tells her to listen to the traffic and guess the configurations of the intersections they pass.

“It’s a two-way,” she says confidently at the intersection of Pearl and Congress streets. “It’s a light.”

Voisine pauses at the intersection of Congress and Exchange streets. This is the final crosswalk of her lesson. The car is just a block away.

“After we cross here, you’re going to turn left,” Dionne said.

Voisine nods her head vigorously.

She starts to step into the street, but immediately jumps back onto the curb as she hears a car approach. The white PT Cruiser makes the turn onto Exchange Street.

A group of teenage girls with Urban Outfitter shopping bags chatter to each other as they cross the street. Voisine reaches a foot onto the asphalt, then pulls it back. She tilts her head and listens to the sounds of passing cars. And then, Voisine quickly steps into the road and strides across. She can’t see the white lines of the crosswalk, but she follows them perfectly. She sweeps her cane in a wide arc in her path, and Dionne hurries behind her to keep up with her quick steps.

Her cane taps the opposite curb, and she turns left.

Megan Doyle can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

mdoyle@pressherald.com

Twitter: megan_e_doyle

Send questions/comments to the editors.