This is a particularly good moment for painting in New York. On the heels of an Agnes Martin blockbuster at the Guggenheim are important shows such as the troublingly tricky modernist Francis Picabia at the Museum of Modern Art and one of the most head-turning and mind-changing shows in decades: Kerry James Marshall at the Met Breuer (the old Whitney); the Marshall exhibit closes today.

Another high point on view now is “Shivers” at MoMA PS1, an exhibition of 24 works by Portland-based painter Sascha Braunig.

Entering her mid-30s, Braunig is young. But the Canadian-born painter has degrees from Yale and Cooper Union and an already crackling heap of success in New York’s gallery scene, where she is represented by Foxy Production. Her style, while evident, is still growing, shifting and evolving with impressively lithe conceptual gymnastics. Braunig is an excellent painter, solid on process, comfortable with ideas and easy to spot even as her work shifts and develops. She is well situated for the long haul. A MoMA show, of course, isn’t going to hurt.

Braunig’s works tend to be small (in the 24 x 20-inch range), but they bristle with a high-value, heavily saturated rhythmic intensity, as though made of coils of brightly colored clay machine-laid onto the painting surface. While at a glance, they act like abstractions, each work ultimately relates to the viewer like a portrait: They are intimate, vertical works on the scale of an actual human face, and they are free of horizon lines.

What we wind up finding within are figures. And while the figure might play, shift or be up to some witty art-historical function, when it comes into view, it will engage like a portrait.

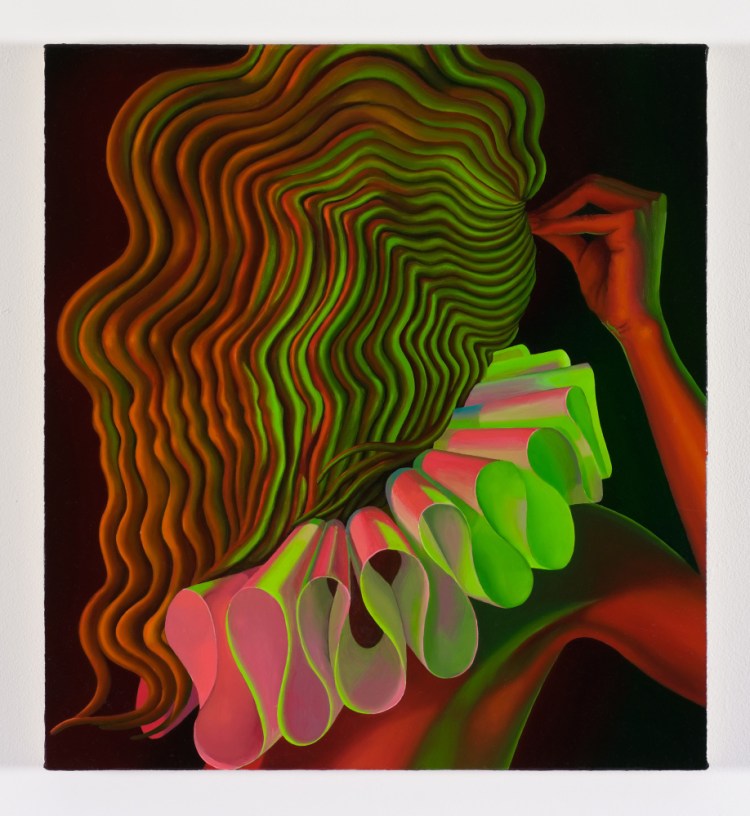

“Herm” by Sascha Braunig.

The sole exception is “Motes,” a tilted grid of cartoony specks floating in space (imagine if the surrealist Yves Tanguy painted jacks tossed into the air). But even this comes around to a figurative connection within the show: Braunig’s most recent works include several tall, vertical pieces from a series titled “Herm” – a terrific title insofar as it implies relations to hermetic, hermaphrodite and the classical pillar sculptures of Hermes placed at borders or crossroads to ward off evil – herms. The herm sculptures were limbless but sometimes included carved male genitals.

In one of Braunig’s “herm” paintings, labial parades of sometimes sensuously opening vertical pipe-stripes, she strategically places a bright pink mote. While the shape first struck me as a reference to Kurt Vonnegut’s asterisk-as-anus leitmotif from “Breakfast of Champions,” Braunig’s herm mote is undeniably a reference to female genitals, but it’s playful, intimate and self-aware: comfortably gendered rather than brazenly sexualized.

Braunig’s work follows a pleasantly pulsing path of female subjectivity in the sense of, say, an introspective moment before a mirror. This personal intimacy appears clearly and powerfully when compared to Kerry James Marshall’s cultural critique of the (male) experience of being a black American.

Braunig’s conveyance reaches out to directly connect the viewer to the artist through the intimacy of scale, paint handling, perceptual nuance and art-historical inspirational caprice. While Marshall and Braunig share many conceptual and philosophical qualities, his work takes a race-broad perspective with the goal of illuminating cultural critique rather than a personal connection. To compare their works in terms of identity reveals the shared but diverging powers of both.

Marshall’s flat black figures are powerful, and his paintings are brilliantly successful, but they are at their best, not as Louvre-scaled tableaux about African-American-oriented housing projects in Chicago, but when they engage on the same person-to-person page as Braunig. To start his show, Marshall presents an uncomfortably blackface-like grinning self-portrait in the scale of Braunig’s earlier (and more obviously self-portraiture) works in “Shivers.”

“Portrait of the Artist & a Vacuum” by Kerry James Marshall.

It was with his next pieces that Marshall had me – particularly his brilliant 1981 “Portrait of the Artist & a Vacuum.” Marshall’s flat black figures, after all, are steeped in the conflict of the being and non-being experience of blacks in America. The vacuum is a stroke of wit that suggests something emptier than emptiness, but it goes much further to issues of domesticity, etc., while the picture of the painted portrait invokes memory, who we value and so on.

This empty space aesthetic is the fundamental aspect of Braunig’s figures. Her figures and faces are generally implied by wires, and the figure is connoted by the space – rather than the material presence – of a person. We see a repeated mask looking to Magritte’s head-shrouded 1928 “Lovers” in works such as Braunig’s “Coverage” or “Bossy Pins.” This last piece in particular, with its ruffled collar, is reminiscent of Rembrandt, but even more poignantly looks to the Italian mannerists like Agnolo di Cosimo Bronzino and Pontormo, whom Braunig salutes with her predilection for couleur-changeant shifting of hues.

“Coverage” by Sascha Braunig.

With 24 of her works, it is much easier to feel the breadth and warmth of Braunig’s engagement with art history. When she looks to historically important artists, Braunig does so respectfully and so opens the common experience door to the viewer. In addition to bits of Vermeer, Michelangelo, Dali, Lynda Benglis and, among others, Picabia, we are treated to a very serious response to Kazimir Malevich and Fernand Leger. The latter (think “Woman with a book” of 1923, for example) is more easily noticed in the shiny undulations of works like “Shade,” but it feels like the true source is Malevich’s cubo-futurist response to Leger, built of spatially tight couleur-changeant blocks (that Braunig would have studied in person at Yale).

Braunig leaves playful traces in the warp and woof of her weaves – a practice not dissimilar to Marshall’s works like “Invisible Man” in which a black man is practically impossible to see on a black background, yet, hilariously, his genitals are covered by a black redaction rectangle – which only draws attention to the political aspects of the invisibility problem. But with Braunig, the motion moves the other way, from invisible – the assumption of abstraction of the first encounter with the painting – to visible in the way a hunter might follow traces to his quarry. This is the same way doctors and detectives work, and it is also how viewers pursue meaning and content in art.

In “Frotteur,” for example, we see only a pulsing surface of orange and teal pipe-stripes, until we notice a hand pushing through the lower left as though through a curtain. Above the hand, an upturned point on a curve is confirmed as a gender-providing nipple when we notice the vague face above it. In turn, this allows the woven form on the right side of the canvas to appear as a long braid of hair – and the figure thus emerges. What is particularly unusual, however, is that we lose sight of the figure in the pulsing neon-ish pipe-stripe jungle as we move away from the image. Typically, a finally-seen figure is hard to leave behind.

Braunig’s newest works play on the idea of theatrical skins as the stuff of painting, wittily welcomed by their surprisingly apt titles: “Hide” (think skin), “Scrim” and “Tenterhooks” (as in the hooks used to connect cloth or hides to a drying rack). These move from the intimate self-portrait sense of the earlier work to a broader depiction of the figure and the ironical blend of sculptural space and theatrical flatness of a stage backdrop. These new pieces interact with the mini-installations the artist sets up in her Congress Street studio. The paintings are oddly true to the installations, and yet the installations arrived as oddly true to Braunig’s already impressive paintings.

Braunig’s broadest subject is subjectivity itself, through which the artist finds her way with nuanced but robust sensitivities and her considerable gift with a brush. Braunig’s paintings in MoMA’s “Shivers” are diminutive and intimate, but they pulse with big power, like a current fed by many lively streams.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 5:36 p.m. on Feb. 2, 2017 to correct the name of Foxy Production.

Send questions/comments to the editors.