Maine water officials are urging hundreds of schools in Maine to test their water for lead – many for the first time – after a water crisis in Flint, Michigan, this year brought nationwide attention to the high levels of lead poisoning in that city’s water supply.

Currently, about 350 schools in Maine that are on municipal water systems have never tested their water for lead, and there is no centralized database that shows which schools have done lead testing, what the results were, and whether action was taken to fix any problems.

Although the state is behind the new effort to get all public schools to test their water, it does not have a plan to track which schools do the testing, or their results, according to Jeff LaCasse, chairman of the Maine Public Drinking Water Commission.

“The results will go to the school, and the (state) lab will have the results, but they’re not planning to put together a database with all the results,” he said, referring to the state agencies involved, which include the departments of Health and Human Services and Education. “Maybe they will going forward.”

That means there is no central location for the public to find out which schools have tested, whether the water was deemed to be safe, or which schools haven’t conducted any tests.

A Lewiston lawmaker is proposing legislation that would require testing the water in all schools on a regular basis, as several other states have already done. New York and New Jersey require 100 percent testing and include some state money to pay for it. Other states, such as Michigan, have provided funds, but do not require testing.

Some states are also mandating that test results be made available online. New Jersey, for instance, is requiring school districts to post the information on district websites, while Massachusetts’ state website posts an updated roster of tests and results.

Exactly what each state is doing to mandate and track lead tests in schools isn’t clear, since some are passing new laws, while others are issuing regulations through state agencies.

“Every state is talking about it in some manner,” but states are taking different approaches, said Doug Farquhar, the environmental health program director at the National Conference for State Legislatures.

The Maine program is intended “to support the state’s water associations, water utilities and schools to encourage voluntary testing for lead by providing free testing and technical assistance,” said Samantha Edwards, the spokeswoman for DHHS. “There is no tracking database. The (Drinking Water Program) will not receive any testing results.”

Parents with questions will need to contact schools directly for information, she said.

“This is a voluntary effort. Schools may or may not choose to test. It is entirely up to them,” Edwards said.

The new effort, which provides 10 free tests per school, is an attempt at a “first pass” round of testing, so school districts know if an issue exists in their schools, LaCasse said. It is far less rigorous and comprehensive than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s standard for lead testing, which requires multiple kinds of tests on every possible drinking water source in a building.

The EPA requires action to remove lead from drinking water when it reaches 15 parts per billion, but the agency also says there is no safe level of lead exposure. Children are especially vulnerable to lead poisoning, which can cause learning and developmental disabilities, behavioral problems and a host of physical ailments.

WELLS VS. MUNICIPAL WATER SUPPLIES

Schools fall into two categories on whether they have to test their water for lead and copper.

Under state and federal requirements, 240 Maine schools that get their water directly from wells must test for lead and copper at least once every three years, report the findings and make any necessary changes. But schools that get water from a municipal water district do not have to test their water, since the utility monitors water quality elsewhere in the overall system.

As a result, most of those schools – about 550 in Maine – have never tested for lead and copper.

Water comes out of a new faucet at Benton Elementary School. The school had high lead levels when its water was tested and has since replaced many of the faucets and water fountains. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

“It’s frankly maddening that we’re not mapping out water quality better,” said Rep. Heidi Brooks, D-Lewiston, who is crafting legislation that will close the gap and require uniform testing of water in public schools. Lewiston-Auburn has the highest rate of childhood lead poisoning in Maine.

According to the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, children younger than 2 who are screened for lead exposure in Lewiston-Auburn test positive for “concerning” blood lead levels at twice the rate of the rest of the state, Brooks said. Out of the 249 1- and 2-year-olds in Maine diagnosed with elevated blood lead levels between 2009 and 2013, 47 were from Lewiston-Auburn, Brooks said.

“We should have zero tolerance for elevated lead levels in the water,” Brooks said.

The scope of the gap in testing is even more pronounced nationwide. Nine of every 10 schools and day care centers in the United States are on municipal water systems, according to the EPA.

Since the beginning of the year, several municipal water utilities in Maine took it upon themselves to contact schools in their district to offer free test sampling kits, or to do the testing themselves.

“We realized maybe our schools aren’t thinking this is an option,” said Portland Water District spokeswoman Michelle Clements. All but one school in the Portland Water District did the testing, and none was found to have elevated lead levels, she said.

About 200 schools in Maine have been tested through those informal methods, according to Roger Crouse, director of the state’s Drinking Water Program, who was monitoring the effort.

But as of last week, about 350 schools still hadn’t done any testing, according to state officials.

“The water quality inside these schools is largely unknown,” read a Dec. 2 letter sent to municipal water utility districts, signed by LaCasse and officials from the Maine Rural Water Association and the Maine Water Utilities Association.

“We encourage you to reach out to the schools you serve,” the letter reads. “You are drinking water professionals and school officials likely do not have your expertise and knowledge about sampling for lead. Any assistance you could provide will help to protect children’s health. We appreciate that you will be going beyond what is required of you by federal or state laws and rules.”

Though health officials have long warned of the dangers of lead poisoning, the issue was thrust into the public spotlight by the recent lead poisoning crisis in Flint, Michigan. Residents there are grappling with a public health crisis created by the decision to switch to a cheaper but more corrosive water source, which caused lead to seep from the city’s pipes into the water supply.

Officials say that scenario is unlikely to happen elsewhere, but the incident highlighted the fact that most schools don’t test their water for lead.

Students and staff at Benton Elementary School are allowed to use the tap water there again after weeks of using only bottled water. Fixtures were replaced throughout the school after tests revealed dangerously high levels of lead and copper. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

EARLY RESULTS IN MAINE

Under the new Maine program, the state’s Health and Environmental Testing Laboratory is providing free sample kits, which cost about $20 each, and analyzing the results. The school districts will be responsible for correcting any problems or conducting additional sampling, LaCasse said.

Out of several hundred schools tested earlier this year, only a handful, including Yarmouth and Benton, had high lead levels. Most districts resolved the problem with low-cost fixes such as replacing water faucets or bypassing old pipes.

Maine Water Co., which serves 21 municipalities across the state, collected several hundred samples from 55 public school buildings in 17 different school districts. They found fewer than 10 had elevated lead levels – six from the same building in Greenville, according to Maine Water President Rick Knowlton.

“We saw very few buildings with elevated lead levels, so that was really good news,” Knowlton said.

School officials said they were happy to have had the results as well, even if it meant fixing a problem.

Benton Superintendent Dean Baker said it took a few weeks to replace all the faucets and drinking fountains at Benton Elementary School, where initial tests showed high levels of lead in three faucets. The issue, he said, was solder in the fixtures.

“We just took the approach that if there was anything that could be done to ensure we had completely safe drinking water, we would do it,” Baker said. “Our district is going to ensure we test every school every year, as a standard.”

The Gorham school district plans ongoing testing as well, even though the initial tests showed no elevated lead levels, said Superintendent Heather Perry.

“It’s better to know than to not know,” Perry said. “This is something we need to know for the safety of our kids.”

Baker praised the state’s efforts to get all schools tested.

“I think it’s good that we’re going to have consistency and accuracy,” Baker said.

Crouse, at the state’s Drinking Water Program, said he’s been working with municipal utilities for a few months, keeping informal notes on what schools were getting tested. But officials realized that approach was too haphazard.

“We realized the public didn’t have a lot of information about what was actually happening,” said LaCasse, who is also general manager of the Kennebec Water District. Since the schools had never had to test their water before, “what we were finding was that the schools didn’t really have a clue.”

The Maine Water Co. reached out to all its schools, as has Portland Water District and the Kennebec Water District.

“They’ve done a lot of testing, and they’ve paid for it through their own resources,” said Crouse. “What we’ve had reported back to us is that when they test, they’re not finding widespread problems.”

But the testing that has been done has varied among the districts.

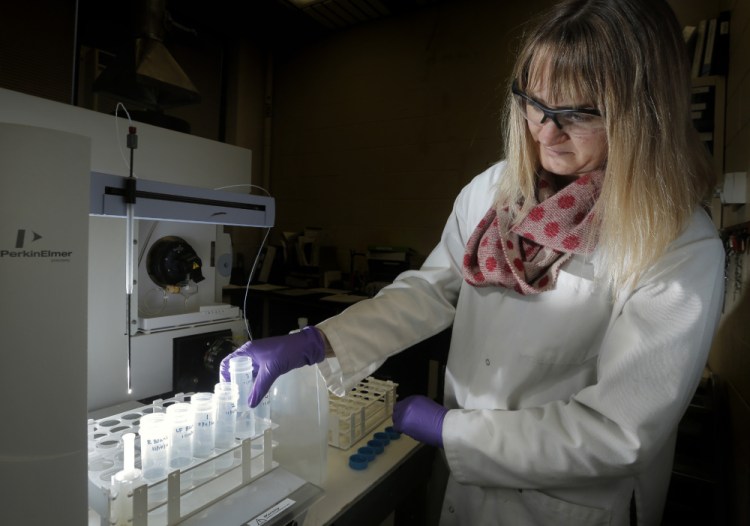

Rebekah Sirois, an environmental scientist for the Portland Water District, demonstrates the water testing process that the water district uses. The district tested water for lead levels last year from most of the schools it serves. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

The Portland Water District tested obvious drinking water sources, such as school kitchens and drinking fountains, but did not test every water source. It also made a point of doing both a “first draw” test – of the water that comes out right when you turn on the faucet – and a “running” sample test, after the water had been running for a minute. At Greenville, five of the six faucets that showed elevated lead levels in the first draw test showed either no detectable lead, or levels below EPA standard levels, in the running test.

But those high levels prompted the school to replace faucets and reroute and replace piping between floors, said district Superintendent Jim Chasse.

“Whenever you say the word ‘lead,’ it’s big,” Chasse said. “When they detected (lead), they shut down every drinking source and brought in bottled water.” Officials eventually pinpointed the likely culprit for the elevated results to one 4-inch section of original pipe.

Crouse said he’s not surprised some districts haven’t tested their water for lead.

“One of the challenges with this is that there are a lot of players that need to buy in. Because it’s all voluntary,” Crouse said. “It’s a little bit like herding cats when there are no regulations. With regulations, it’s ‘you shall do this’ and that’s the clarity.”

“It’s the fear of the unknown. You are already maxed out. Schools are short on resources and there’s controversy,” he said.

“This is not unique to Maine. Every state is kind of thinking about this.”

A NATIONWIDE ISSUE

Multiple states have already passed legislation requiring all schools to test their water, and federal bills have been proposed to provide federal grants to fund testing.

• In New York, Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed a bill in September requiring mandatory testing in all New York schools by Oct. 31, making it the first state in the nation to complete lead testing all school districts.

• In New Jersey, the state Board of Education adopted new regulations in July requiring testing for lead in all drinking water outlets within a year. The districts must make test results available to the school community, on the district website and notify the state Department of Education. The DOE is reimbursing the cost of collection and testing by a state certified laboratory.

• In Massachusetts, $2 million in state funds were made available for testing. The state website not only shows the results of the testing, but maintains an up-to-date roster of action taken by schools that reported elevated levels of lead or copper, such as posting “hand washing only” signs on faucets and replacing plumbing and/or fixtures.

• In Ohio, a state law passed in June provides up to $15,000 per building to school districts for replacing lead pipes and fixtures as well as reimbursement for some costs of water testing.

Additionally, the EPA is currently reviewing its lead and copper testing standard, but that’s a yearslong process.

“Schools served by a (public water system) can implement a voluntary lead reduction program,” the EPA advises on its website.

But in a post-Flint analysis, the EPA did note the lead and copper rule gap of not requiring testing in schools.

The “regulation and its implementation are in urgent need of an overhaul,” the white paper read. The EPA regulation “only compels protective actions after public health threats have been identified.”

Farquhar, of the National Conference for State Legislatures, said regular testing is a good idea and could head off the need for strict regulation.

“If you have an engineer go out and test at schools, once every year or once every five years – make it a regular occurrence – then you are going to avoid coming up with these situations. You want to be ahead of the problem,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.